Bernie Leadon on 'Laurel Canyon' Doc, Gram Parsons, Future With the Eagles

Social distancing is easy for , who lives on a farm outside of Nashville. “It’s over 300 acres, so I can walk around with nobody there,” says the former guitarist. “So basically, I live in a park. I’m fortunate.”

Leadon is featured in the upcoming docuseries, which arrives on Epix in two parts on May 31st and June 7th. He hopped on the phone to discuss the film, his friendship with , and the possibility of reuniting with the Eagles.

Alison Ellwood, who directed the new docuseries, also worked on the History of the Eagles documentary — but Laurel Canyon shows your career from a broader lens, from Dillard & Clark to the Flying Burrito Bros. How did that feel for you?

Well, may I ask, approximately how old are you?

I’m almost 30.

Okay. So, this is where I want to put it in perspective. When I was in my twenties, people that were talking about what went on 50 years ago were talking about World War I. Where now, they’re talking about Vietnam. It’s hard for me to believe that we’re talking about 50 years ago.

And here’s the other thing: I don’t think I’m done yet. I’m just like, “Wow, okay. I’ve had a really long career, but I’m not dead.” I’m still writing songs.

If somebody told your 30-year-old self that in 2020, there would be not one but two documentaries chronicling your life in music, what do you think you would’ve said?

“Wow, fantastic.” Laughs.] I guess I did okay.

The documentary shows a photograph that Henry Diltz took of your silhouette facing Los Angeles in 1979. What do you remember about it?

I was going to use it for an album that never got made. We had to stage it because you have the landscape down below. We looked at the city lights from different parts of the Santa Monica Mountains and decided you had to be pretty close. So we went into Hollywood and found a place to put me.

Then — this is kind of cool — in order to have it be just the city lights behind but to get enough light on me, there was a time lapse to expose the photograph. Henry was the photographer, but Gary Burden was the art director, and he was down in the bushes below me with a flashlight. The lens was open for a second or longer. Gary was painting my face with a flashlight, just illuminating it, while the lens was open. It was a neat effect.

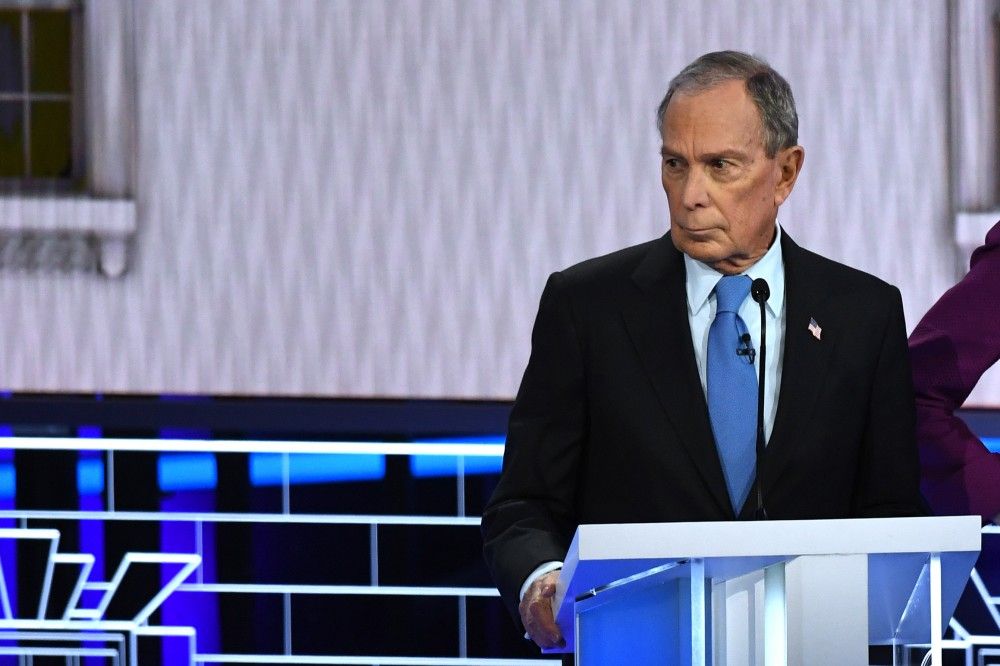

Photo by Henry Diltz

Henry Diltz

There’s a lot in the documentary about Gram Parsons, who’s become this mythical figure in the scene you were part of. What was he like as a person?

If you want to go down as an icon, it’s a very good part of your business plan to die young, because you get frozen in time. You have a chance to become an icon while your peers are still around.

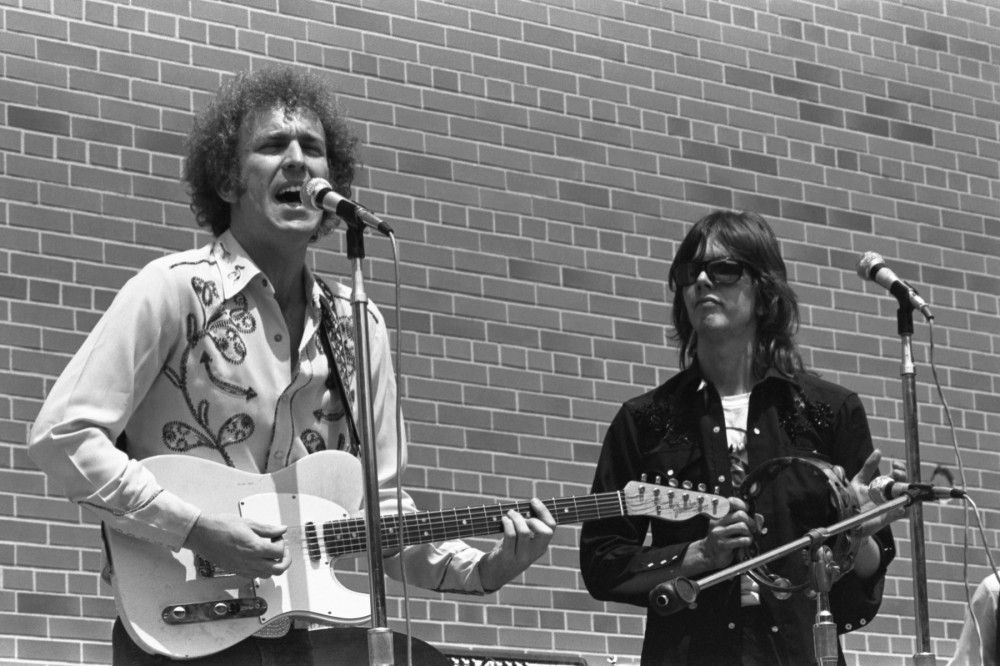

Gram was a lovely guy, especially when I first knew him. I knew Chris Hillman when we were both in our teenage years in San Diego. He was Gram Parsons’ partner in , and the Flying Burrito Brothers were on the same label as Dillard & Clark, which I was in. We were all on the A&M film music lot together. So anyway, after the Burritos’ first album, their bass player left and they had an opening. I didn’t really know Gram, but I joined the band. I was 23, and Gram was about the same age. Chris was maybe 24 or 25. We were all pretty young, and we weren’t very damaged yet, especially physically.

Gram was very gregarious, outgoing, funny. We were all so young that we didn’t think of ourselves as being possible alcoholics or addicts, but everybody in our peer group drank and did drugs. Certain people had a tendency to go over the edge. We all would have a couple of beers and maybe smoke a joint or something, but Gram tended to get out beyond that.

The second Burrito album was Burrito Deluxe. We did it in ’70. Then the Rolling Stones came to Los Angeles for a summer, and Gram started hanging out with them. He tried to keep up with Keith Richards, and he couldn’t do it. Gram morphed and changed into somebody who was more of a drug addict and less his jol, funny, youthful self, more affected by the drugs. He changed quite a bit in personality over the year-and-a-half that I worked with him. It’s pretty dramatic, because he died at 26.

You returned to the Eagles in 2013. What was that like after all those decades away?

Well, the songs were essentially the same, and they’d been doing basically my parts. I carried on, I just took over playing my parts, the intros and the leads on the songs that I had played on. It was interesting. I’d spoken to or seen the guys through the years occasionally, and we fell back into working together.

When we were playing and singing, it was all very natural. I was grateful that the tour structured the show so that we started out with just Don and Glenn singing an acoustic waltz “Saturday Night”], and then I came out and we played one song with just the three of us “Train Leaves Here This Morning”], and then they added Tim Schmit on bass and we did “Peaceful Easy Feeling.” Then they added Walsh and we did “Witchy Woman,” but all sitting on amps in a small setting in the middle of the stage without any backing musicians. That was my favorite part of the show, because that recreated the sound that we had in the beginning.

We were just a four-piece for first three years of the band, and then we added Don Felder, became a five-piece band, and then the music changed. But the early stuff was folk influence, vocal-centric, and had some country stuff in it, and rock and R&B influences as well. It was pretty open-sounding and live-recorded, just guys playing and singing acoustic and electric instruments. That was the original Eagles sound.

We were able to recreate that on stage for the first five songs every night. That was really cool, to hear just the voices with a couple of acoustic guitars. Then, the rest of the show, they brought the rest of the backing band. So, there was another five people, there was another drummer so that Don] Henley could come out front. There was an organ player, a piano player and percussion player.

So the sound got bigger, became more arena-sized, because that’s what we were playing. The sound had to get bigger to sustain a show, and that was more what the Eagles had been doing since I had left. What it had grown into was a massive touring show with a hundred crew members and the band and a bunch of buses and semi trucks and a jet airplane. That’s how big it was. Yee-haw, it had grown into quite a big thing.

I saw the Eagles right before the pandemic hit, and was shocked by how many people were onstage.

Oh, I haven’t seen the show since I left. I thought Deacon Frey] did a great job on “Peaceful Easy Feeling.” Once we did it at Glenn Frey’s] memorial. I think he’s a good singer and represents that stuff really well. And I know Vince Gill’s] daughter, who’s a friend as well. He lives in Nashville. He’s a fantastic player, a fantastic singer, a lot of styles, so I have tremendous respect for Vince. I’m sure he is doing a great job with it.

Do you ever see yourself playing with them again?

Well, never say never. Right? Interestingly, when the two-and-a-half years of touring was over the last show, Glenn Frey gave me a big hug and said, “It’s not over,” and I went, “Okay. Cool, man. Let’s talk about it.” Glenn’s not here, so that can’t happen.

Honestly, I don’t really see it happening unless it maybe it’s just a one-off or special occasion kind of thing. I don’t think it will, but never say never. I’m good friends with the guys, so there’s no impediment to it. I don’t think it will.