Yesterday's Gone: Iowa Was Waterloo for Democrats

Monday, February 3rd, just before 9 p.m., the airport Holiday Inn, Des Moines. A crowd of supporters and volunteers for Senator is buzzing. After four years of being shat upon by party officials and media allies alike (CNN and MSNBC are seen in Sanders crowds as Goebbelsian arms of the Democratic National Committee), Vermont’s anti-corporate crusader has defied odds and soared in polls. All that remains is the Schadenfreude orgasm of a victory speech.

A young animal rights lawyer named Colin Grace is explaining how he got turned on to Bernie. “Honestly, it started by looking into some of the causes of 2008,” he laughs. “Well, then I found weed and became a libertarian.”

A nearby supporter with long hair under a standard issue Spin Doctors wool weed-smoking hat perks up. “Dude, should we all smoke right now?” smiles at a fortysomething named David, patting his chest pockets. “I’ve got the most enormous J.”

Everyone laughs. David and his wool-and-fleece costume looks nothing like the younger Grace in a blue blazer and collar — Grace was a caucus precinct captain tonight — but their stories sound the same. Two elements are near-constants in Sanders crowds: life experience with a broken system (Grace told a story of corporate-captured regulators killing an animal rights bill he worked on), and feelings of sympathy for a Senator also seen as getting the short stick from establishment cheats.

“I was third party in 2016. I supported Gary Johnson,” says Grace. “But then, even from the sideline, I thought, ‘Man, the DNC is rigging this against Sanders.”

“They’re dirty, man,” David agrees. “They don’t even try to hide it.”

Nods all around. The group breaks up to hunt for a TV. The results are about to come in. A young woman in a blue Bernie shirt mutters as she walks toward the conference room: “I can’t wait to see Wolf’s face.”

There was so much scummery to avenge: from Chris Matthews on MSNBC suggesting Sanders wouldn’t stop his car to help someone injured on the side of the road, to CNN running a late-breaking story that the DNC was employing “troll fighters” to combat a Russian “disinformation” campaign (presumably to help Sanders), to the DNC changing debate rules to allow billionaire ex-Republican Michael Bloomberg to buy his way in, to an $800,000 attack ad campaign from former Democratic strategist Mark Mellman, to reports that at least some DNC members were contemplating a return of superdelegates to stop Bernie.

It was all out war, between what one Andrew Yang supporter described as being between “the screwers and screwees.” It felt like the same kind of below-the-belt mudslinging progressives used to associate with Republican hitman Lee Atwater.

Sanders supporters felt sure they’d overcome. With a win, all that invective was just another indication of righteousness.

“It just tells me he pisses off the right people,” Grace quipped. Then he walked off to catch the victory speech, and all hell broke loose.

***

Yesterday’s really gone.

In 1993, liberal America sang along at the Bill Clinton inaugural ball with Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks (and Michael Jackson, whoops). “Don’t Stop” was “Ding, dong, the witch is dead!” for the smart set. The New Democrats ushered in a new reign for youth and modernity against Reagan-Bush reaction.

That’s done. After a vote in Iowa that reeked of third-world treachery — from monolithic TV propaganda against the challenger to rumors of foreign intrusion to, finally, a “botched” vote count that felt as legitimate as a Supreme Soviet election — the Democrats have become the reactionaries they once replaced.

Coinciding with the flatulent end of the party’s impeachment gambit, and the related news that Donald Trump is enjoying climbing approval ratings, the Blue Party was exposed as an incompetent lobby for doomed elites, dumb crooks with nothing left to offer but their exit.

Waukee, Iowa, Thursday, January 30th. Activist Tracye Redd, a Waterloo native who’d repped Black Lives Matter and Greenpeace in the past and was currently “bird-dogging” candidates for the Center for Biological Diversity, approached former Vice President after a speech. He asked if Biden would agree to work toward phasing out fossil fuels.

Before he knew it, Biden was sticking a finger in his chest and angrily reading off credentials. “Go back. 1986. I was the first one ever to introduce a climate change bill,” he snapped.

“I thought to myself, ‘Great, you did that in 1986, but if we’ve got a million species facing extinction, so it’s clearly still a problem,’” Redd remembers.

Biden pushed again. “Politifact said it’s a game changer,” Biden jabbed, adding: “I’ve been working my whole life.” He poked Redd in the sternum on fact, work, whole, and life, then walked away like he’d dropped a mic.

The scene was so bizarre that Redd says he could only respond by instinct, drawing on post-Trayvon Martin strategies for black men to keep safe in charged situations. “You know, ‘Yessir, no sir,’ don’t talk back, keep your hands visible…”

Biden in this race has, on multiple occasions, looked close to grabbing prospective voters by the ears and speed-eating their faces off to thwart questions. A few days before the exchange with Redd, he grabbed a former state representative named Ed Fallon by the jacket lapel and asked, “You believe Bernie can do something, and by 2030? Only relaxing when Rollins gasped he was for Tom Steyer. Often he looks around like he expects a thumbs-up for giving in to his rage-response.

In Cedar Rapids on February 1st, Jaimee Warbasse, a mother, hairstylist, and onetime caucaser for Hillary Clinton, was feeling anxious. Just days were left before the vote, and unusually, she was undecided. Her husband Matt called her with good news: Joe Biden was going to appear at the Roosevelt Middle School, just down the street.

“I was glad,” Warbasse recalls. “When he was Vice President, I thought he’d make a good president… I was hoping to meet him, so I could feel more comfortable voting for him.”

Iowans take presidential politics seriously. Perhaps only New Hampshire residents could comprehend. When deciding whom to stand for, Iowans expect to physically meet their candidate. This is seen as a two-way obligation: Voters should make an effort to meet the hopefuls, but candidates also have to make themselves available.

Warbasse was slightly put out that she had not met Biden. “There were more opportunities to see the other candidates,” she said. She went to his speech, then got in a greeting line, shouting, “Undecided voter over here, Joe!”

She invited him to make his case. “I haven’t seen much of you,” she said. Why should she vote for him?

Biden moved inches from her face, gripped her hand (throughout: “we’re talking minutes,” she said) and gave a political clip-art answer, about how he’s a guy who says what he means and means what he says, etc.

When Warbasse didn’t respond with enthusiasm, his mood turned. “If I haven’t swayed you today, then I can’t sway you,” he snapped.

Warbasse was shocked. “It was like he was waiting for people to tell him what a wonderful person he was,” she says. “It was super bizarre.”

These scenes have been laughed off as irrelevant dementia, but Biden’s outbursts are in keeping with a long pattern of establishment Democrats being outraged at having to explain their shit records.

The Biden jab came from the same place as the counter-accusatory finger Bill Clinton thrust at Black Lives Matter protesters in Philadelphia in 2016, for questioning the Crime Bill and talking about “super predators” (“Maybe you thought they were good citizens. She didn’t!” Clinton shouted). It was the same impatience that got Nancy Pelosi huffing over progressives and “the Green Dream or whatever.”

Democratic campaign events have long been more pep rally than discussion, more about the terribleness of Republicans than substance. “They’re so used to events where everyone is rooting for them,” says Redd. “It’s like, ‘No, we’re actually here to challenge you on issues that matter.’”

Biden performed surprisingly well all year in polls, but he headed into Iowa like a passenger jet trying to land with one burning engine, hitting trees, cows, cars, sides of mountains, everything. The poking incidents were bad, but then one of his chief surrogates, John Kerry, was overheard by NBC talking about the possibility of jumping in to keep Bernie from “taking down” the party.

“Maybe I’m fucking deluding myself here,” Kerry reportedly said — mainstream Democrats may not have changed their policies or strategies much since Trump, but they sure are swearing more — then noted he would have to raise a “couple of million” from people like venture capitalist Doug Hickey.

Kerry later said he was enumerating the reasons he wouldn’t run, though those notably did not include humility about his own reputation as a comical national electoral failure, or because there’s already a candidate in the race (Biden) he’d been crisscrossing Iowa urging people to vote for, but instead because he’d have to step down from the board of Bank of America and give up paid speeches. French aristocrats who shouted “Vive le Roi!” on the way to the razor did a better job advertising themselves.

With days, hours left before the caucuses, there were signs everywhere that the party establishment was scrambling to find someone among the remaining cast members to stop what Kerry called the “reality of Bernie.”

But who? Yang said smart things about inequality, so he was out. Tulsi Gabbard was Russian Bernie spawn. Tom Steyer was Dennis Kucinich with money. Voters had already rejected potential Trump WWE opponents like the “progressive prosecutor” (Kamala Harris), the “pragmatic progressive” (John Delaney), “the next Bobby Kennedy” (Beto O’Rourke), “Courageous Empathy” (Cory Booker), Medicare for All can bite me (John Hickenlooper), and over a dozen others.

Former South Bend, Indiana Mayor seemed perfect, a man who defended the principle of wine-based fundraisers with military effrontery. New York magazine made his case in a cover story the magazine’s Twitter account summarized as: “Perhaps all the Democrats need to win the presidency is a Rust Belt millennial who’s gay and speaks Norwegian.” (The “Here’s something random the Democrats need to beat Trump” story became an important literary genre in 2019-2020, the high point being Politico’s “Can the “F-bomb save Beto?”).

Buttigieg had momentum. The flameout of Biden was expected to help the ex-McKinsey consultant with “moderates.” Reporters dug Pete; he’s been willing to be photographed holding a beer and wearing a bomber jacket, and in Iowa demonstrated what pundits call a “killer instinct,” i.e. a willingness to do anything to win.

Days before the caucus, a Buttigieg supporter claimed Pete’s name had not been read out in a Des Moines Register poll, leading to the pulling of what NBC called the “gold standard” survey. The irony of such a relatively minor potential error holding up a headline would soon be laid bare.

However, Pete’s numbers with black voters (he polls at zero in many states) led to multiple news stories in the last weekend before the caucus about “concern” that Buttigieg would not be able to win.

Who, then? was cratering in polls and seemed to be shifting strategy on a daily basis. In Iowa, she attacked “billionaires” in one stop, emphasized “unity” in the next, and stressed identity at other times (she came onstage variously that weekend to Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5” or to chants of “It’s time for a woman in the White House”). Was she an outsider or an insider? A screwer, or a screwee? Whose side was she on?

A late controversy involving a story that Sanders had told Warren a woman couldn’t win didn’t help. Jaimee Warbasse planned to caucus with Warren, but the Warren/Sanders “hot mic” story of the two candidates arguing after a January debate was a bridge too far. She spoke of being frustrated, along with friends, at the inability to find anyone she could to trust to take on Trump.

“It’s like we all have PTSD from 2016,” she said. “There has to be somebody.”

***

Just after sundown, February 2nd, Jethro’s BBQ n’ Pork Chop Grill, Johnston, Iowa. The Niners are up on the Chiefs 3-0 and this gymnasium-sized sports bar is packed. Most everyone in seats is a supporter of Minnesota Senator .

Everyone else in the massive crowd seems to be a reporter or cameraperson. You can’t step two feet in the Des Moines area on caucus weekend without hitting press. It’s like an angry God shook a box of us through the clouds.

When the candidate herself shows up, media engulf her with a three-level swarm. Klobuchar ends up inside a row of cameras inside a row of hacks carrying notebooks, inside a row of taller hacks on tippy-toes.

“I’m asking you to run for me,” she cries, to the scattered real people somewhere beyond the press. “Just like those guys are running on the field. I’m asking you to take this over the goalposts for me. I’m asking you to score a touchdown for — okay, enough!”

Guffaws! Reporters love “Amy,” who goes by one name behind press ropelines, like Shakira, or Sinbad. She’s their take on a star. “Amy” in the last week surged in polls, having overtaken Warren in some surveys, hitting as much as 10, 12, and 13 percent.

Klobuchar is a pure distillation of “electability,” i.e. a Washington reporter’s idea of what a Midwesterner finds charming. She isn’t funny, but her tireless marketing of her funniness matches the reportorial concept of what a “sense of humor” is in politics.

Her ability to speak at length without revealing deep ideological belief is also prized by our kind. This is what Washington for decades told people they wanted, instead of health care, peace, job security, etc.

Scott Thompson, the former mayor of a downstate Illinois town called Rushville, sees it differently. The congenial labor economist dressed in a big green “Amy” t-shirt has a long-standing ritual, asking every reporter who approaches him to sign a clipboard.

“Five today,” he says, chuckling. He holds it up: He’s running out of space.

Thompson’s experience in government disinclines him to politicians who offer facile solutions. He wrestles with the Bernie phenomenon, saying he understands it more now than he used to, as he sympathizes with those who are so mad, they’ve lost faith in the system.

“But at some point,” he says, “you have to stop being pissed off and start working.” He pauses. “If you want to fight just to fight, go into boxing, you know?”

That Sunday night, a 36-year-old Minnesotan named Chris Storey called a number he’d given, for a woman who was chair of the Waukee 4 district. Thanks to a new rule allowing out-of-state volunteers to be precinct captains, he was set to represent the Sanders campaign there.

“We got along, it was great,” he recalls. “She told me she was looking forward to seeing me the next day.”

The next day, caucus day, Storey showed up at Shuler Elementary School in Clive, Iowa. The same official he’d spoken with the night before met him at the door. “It was like two different people,” he recalls. “I was told there was a written directive from the county chair that nonresidents could not be precinct captains.”

Sanders had to get a last-minute replacement captain in Waukee 4, someone not formally aligned with the campaign. He fell short of bility there by five votes. County chair Bryce Smith, who made the decision, said he was responding to a late directive from the Iowa Democratic Party that said they would allow one nonresident captain per campaign, per precinct, but “the discretion of the chair is what goes,” i.e. this ultimately was a judgment call for county chairs. Smith said he didn’t like the change to the longstanding rule — “What’s stopping a campaign from hiring professional persuaders and high profile people?” he asked — and decided to bar nonresident captains. The IDP has not yet commented.

As a result, some would-be captains in Dallas County from multiple different campaigns were pulled off the job (Smith said he got “five, six, eight” calls to complain). Meanwhile, in other districts, nonresident captains were common.

Caucus participants later in the week would offer an eyebrow-raising number of other issues: bad head counts, misreported results, misreads of rules, wrong numbers, telecommunications errors, and other problems.

The basics of the caucus aren’t hard. You enter a building that is poorly ventilated, too small, and surrounded by mud puddles — usually a school gym. You join other people who plan on voting your way, gathering around the “precinct captain” for your candidate. If your pile of people comprises 15% of the room or more on the first count, your candidate is deemed “ble” and you must stay in that group. If your group doesn’t reach 15%, you must move to a new group or declare yourself undecided. There is a second count, and it should be done.

When historians pore over the Great Iowa Catastrophe of 2020, much of the blame will be focused on Acronym and Shadow, the two firms associated with the balky app that was supposed to count caucus results. For the conspiratorial-minded, the various political connections will be key: Acronym co-founder Tara McGowan is married to Buttigieg strategist Michael Halle, while former Obama campaign manager David Plouffe sits on Acronym’s board. Shadow had also been a client of both the Buttigieg and Biden campaigns in 2019.

But garden variety disorganization and stupidity were the major storylines underneath the terrible optics. From the first moment the caucus proceedings were delayed Monday night due to what the Iowa Democratic Party called “inconsistencies in the reporting,” Sanders supporters in particular felt in déjà vu territory. Orlando native Patty Duffy, an out-of-stater who captained for Sanders in the small town of Milo, had flashbacks to the run-up to the Hillary-Bernie convention.

“It was like we were back in 2016,” Duffy said. “Except this was worse.”

***

What happened over the five days after the caucus was a mind-boggling display of fecklessness and ineptitude. Delay after inexplicable delay halted the process, to the point where it began to feel like the caucus had not really taken place. Results were released in chunks, turning what should have been a single news story into many, often with Buttigieg “in the lead.”

The delays and errors cut in many directions, not just against Sanders. Buttigieg, objectively, performed above poll expectations, and might have gotten more momentum even with a close, clear loss, but because of the fiasco he ended up hashtagged as #MayorCheat and lumped in headlines tied to what the Daily Beast called a “Clusterfuck.”

Though Sanders won the popular vote by a fair margin, both in terms of initial preference (6,000 votes) and final preference (2,000), Mayor Pete’s lead for most of the week with “state delegate equivalents” — the number used to calculate how many national delegates are sent to the Democratic convention — made him the technical winner in the eyes of most. By the end of the week, however, Sanders had regained so much ground, to within 1.5 state delegate equivalents, that news organizations like the AP were despairing at calling a winner.

This wasn’t necessarily incorrect. The awarding of delegates in a state like Iowa is inherently somewhat random. If there’s a tie in votes in a district awarding five delegates, a preposterous system of coin flips is used to break the odd number. The geographical calculation for state delegate equivalents is also uneven, weighted toward the rural. A wide popular-vote winner can surely lose.

But the storylines of caucus week sure looked terrible for the people who ran the vote. The results released early favored Buttigieg, while Sanders-heavy districts came out later. There were massive, obvious errors. Over 2,000 votes that should have gone to Sanders and Warren went to Deval Patrick and Tom Steyer in one case the Iowa Democrats termed a “minor error.” In multiple other districts (Des Moines 14 for example), the “delegate equivalents” appeared to be calculated incorrectly, in ways that punished all the candidates, not just Sanders. By the end of the week, even the New York Times was saying the caucus was plagued with “inconsistencies and errors.”

Emily Connor, a Sanders precinct captain in Boone County, spent much of the week checking results, waiting for her Bernie-heavy district to be recorded. It took a while. By the end of the week, she was fatalistic.

“If you’re a millennial, you basically grew up in an era where popular votes are stolen,” she said. “The system is riddled with loopholes.”

Others felt the party was in denial about how bad the caucus night looked.

“They’re kind of brainwashed,” said Joe Grabinski, who caucused in West Des Moines. “They think they’re on the side of the right… they’ll do anything to save their careers.

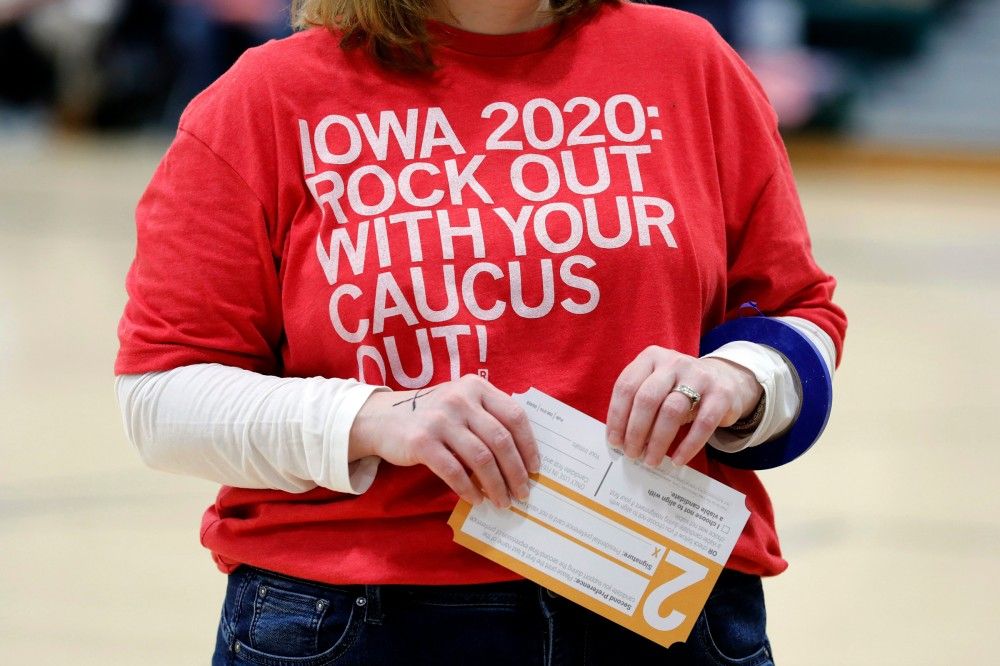

An example of how screwed up the process was from the start involved a new twist on the process, the so-called “Presidential Preference Cards.”

In 2020, caucus-goers were handed index cards that seemed simple enough. On side one, marked with a big “1,” caucus-goers were asked to write in their initial preference. Side 2, with a “2,” was meant to be where you wrote in who you ended up supporting, if your first choice was not ble.

The “PPCs” were supposedly there to “ensure a recount is possible,” as the Polk County Democrats put it. But caucus-goers didn’t understand the cards.

Morgan Baethke, who volunteered at Indianola 4, watched as older caucus-goers struggled. Some began filling out both sides as soon as they were given them.

Therefore, Baethke says, if they do a recount, “the first preference should be accurate.” However, “the second preference will be impossible to recreate with any certainty.”

This is a problem, because by the end of the week, DNC chair Tom Perez — a triple-talking neurotic who is fast becoming the poster child for everything progressives hate about modern Dems — called for an “immediate recanvass.” He changed his mind after ten hours and said he only wanted “surgical” reanalysis of problematic districts.

No matter what result emerges, it’s likely many individual voters will not trust it. Between comical videos of apparently gamed coin-flips and the pooh-poohing reaction of party officials and pundits (a common theme was that “toxic conspiracy theories” about Iowa were the work of the Trumpian right and/or Russian bots), the overall impression was a clown show performance by a political establishment too bored to worry about the appearance of impartiality.

“Is it incompetence or corruption? That’s the big question,” asked Storey. “I’m not sure it matters. It could be both.”

***

Iowa was the real “beginning of the end,” to a story that began in the Eighties.

Following the wipeout 49-state, 512 electoral vote loss of Walter Mondale in 1984, demoralized Democratic Party leaders felt marooned, between the awesome fundraising power of Ronald Reagan Republicans and the irritant liberalism of Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition.

To get out, they sold out. A vanguard of wonks like Al From and Senator Sam Nunn at the Democratic Leadership Council devised a marketing plan: two middle fingers, one in each direction.

They would steal financial support for Republicans by out-whoring them on economic policy. The left would be kneecapped “triangulation,” i.e. the public reveling in the lack of choices for poor, minority, and liberal voters.

Young pols like Bill Clinton learned they could screw constituents and still collect from them. What would they do, vote Republican? Better, the parental scolding of disobedient minorities like Sister Souljah combined with the occasional act of mindless sadism (like the execution of mentally ill Ricky Ray Rector) impressed white “swing” voters, making “triangulation” a huge win-win — more traction in red states, less whining from lefty malcontents.

Democrats went on to systematically rat-fuck every group in their tent: labor, the poor, minorities, soldiers, criminal defendants, students, homeowners, media consumers, environmentalists, civil libertarians, pensioners — everyone but donors.

They didn’t just fail to defend groups, but built monuments to their betrayal. They broke labor’s back with NAFTA, embraced mass incarceration with the 1994 Crime Bill, and ushered in the Clear Channel era with the Telecommunications Act of 1996. Welfare Reform in 1996 was a sellout of the Great Society (but hey, at least Clinton kept the White House that year!). The repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act gave us Too Big to Fail. Shock Therapy was the Peace Corps in reverse. They sold out on Iraq, expanded Dick Cheney’s secret regime of surveillance and assassination, gave Wall Street a walk after 2008, then lost an unlosable election, which they blamed on a conspiracy of leftist intellectuals and Russians.

Still, if you were black, female, gay, an immigrant, a union member, college-educated, had been to Europe, owned a Paul Klee print or knew Miller’s Crossing was a good movie, you owed Democrats your vote. Why? Because they “got things done.”

Now they’re not getting much done, except a lost reputation. That feat at least, they earned. To paraphrase the Joker: What do you get when you cross a political party that’s sold out for decades, with an electorate that’s been abandoned and treated like trash?

Answer: What you fucking deserve!