Why No One Played the Boss Like Lance Reddick

Lance Reddick was an actor with authority.

I don’t just mean that he played lots of authority figures. Lord knows he did. No actor on television in this century may have played more law-enforcement commanding officers than Reddick, who was Baltimore Police task force chief (and later, briefly, commissioner) Cedric Daniels on The Wire, FBI supervising agent Phillip Broyles on Fringe, and LAPD commissioner Irvin Irving on Bosch, among others. He also played CEOs (on Comedy Central’s Corporate), fixers (as the influential concierge Charon in the John Wick films and as Matthew Abbadon on Lost), and one of the final roles he filmed was as Zeus, the leader of the entire Greek pantheon of gods, on the upcoming Percy Jackson series.

In this business, there is always typecasting, and once The Wire became a cult sensation, Reddick was never going to lack for work in this particular area. But many actors can play bosses. Few of them, though, could do it with as much magnetism, conviction, and nuance as Reddick, who died today at 60. You didn’t hire him because he had done it before. You hired him because he did it as well as anyone ever has. Again and again, he took roles that could have easily come across as stock and thankless, and he made them feel as real and compelling as the would-be heroes of the piece. He would not, could not, be ignored, either by his subordinates or by the audience.

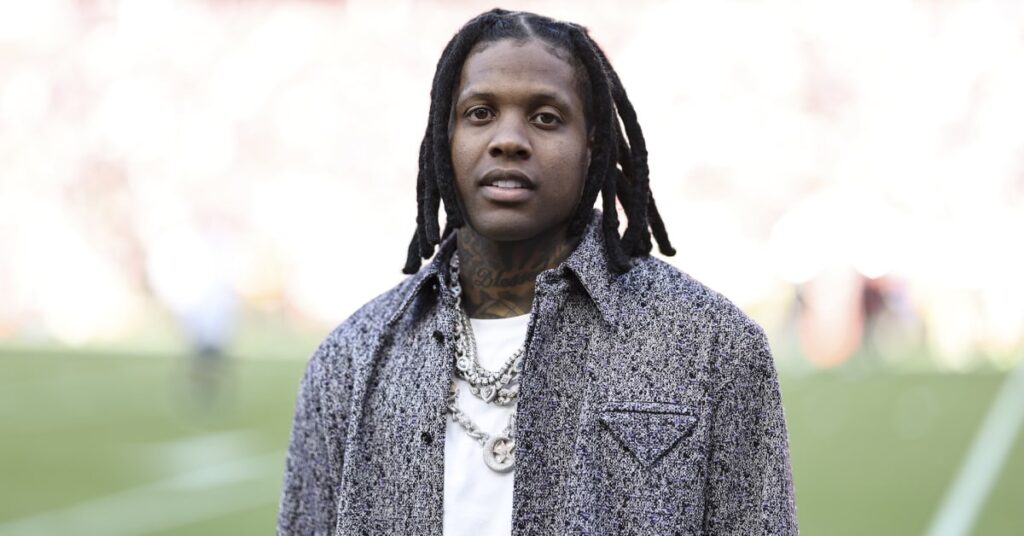

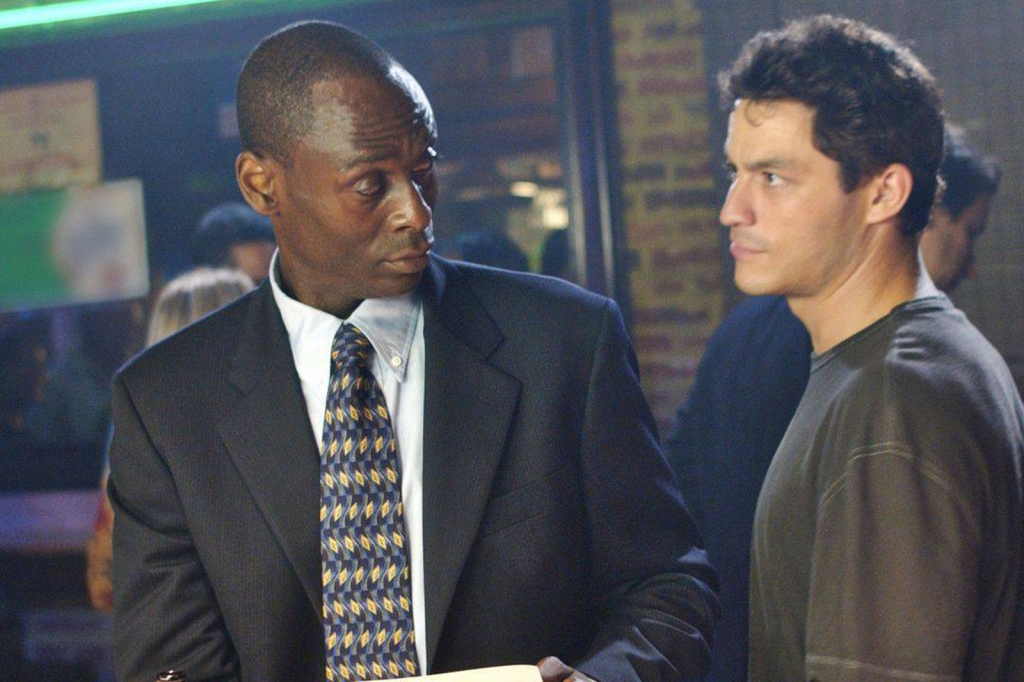

Reddick with Dominic West as McNulty.

Paul Schiraldi/HBO

He had been acting on screen for years before The Wire, including a memorable stint on the HBO prison drama Oz as an undercover cop who eventually becomes a genuine convict. But his career story really begins with Cedric Daniels. The Wire for the most part didn’t bother with two-dimensional villains (unless, that is, they worked at the Baltimore Sun). Still, Daniels was initially set up as something of an antagonist to Detective Jimmy McNulty — a loyal company man reluctantly forced to supervise McNulty’s reckless quest to take down the local Barskdale drug crew by any means necessary. The audience was conditioned by decades of television to root for McNulty — conditioning that The Wire was counting on — and thus to be irked early on that Daniels wasn’t fully on-board with this mission. But Reddick invested Daniels with such obvious dignity and humanity that it was hard not to sympathize with him even before the writing began to make clear that McNulty was a narcissistic asshole with little concern for the welfare of others. By the end of the season, Daniels insists on joining McNulty to invade the Barksdales’ strip club headquarters, and it feels he’s earned the victory at least as much as his subordinate officer. In later seasons, Daniels would be presented as among the series’ more purely heroic characters, eventually making genuine efforts at reforming the dysfunctional department before losing his job due to yet another McNulty fuck-up.

Reddick was always a striking physical presence: tall and angular, with a face and muscles cut like diamonds. He moved with precision, and he had that disapproving rumble of a voice. He naturally spoke in a higher register (below is a clip of him chatting with me about Fringe at Comic-Con a dozen years ago) and otherwise came across as a much more light-hearted figure in person than in most of the roles he played. But the man knew his own instrument, and knew how to make it sing.

As he moved from job to job, he always managed to find something more than might have been there in the material. On Bosch, he played a character who in the Michael Connelly novels had mostly been a cartoonish internal foe for the title role. Reddick played Irving as a hardass who had little patience for Bosch, but never as an outright bad guy. Within a season or so, the series had evolved into an ensemble drama where the ongoing story of Irving’s political career was at least as important as the various killers Bosch kept chasing. And when the series devoted a season to the hunt for the men who killed Irving’s cop son (admittedly, a story taken from the books), Reddick brought so much grief and vulnerability to the moment that it suddenly felt like his show for a while, with Bosch and the other characters working in support of him. He also has the most memeable moment of that series, where Irving gets to silently dismiss a vanquished political foe, Reddick’s face speaking volumes with the most minute change of expression.

That moment was one of many examples of just how much humor Reddick could find even in the heaviest of roles. Corporate deliberately leaned into all of his most commanding attributes, like in this scene where his character disapproves of the company’s new Casual Friday policy:

But he could do it a lot more subtly than that. In the John Wick films, he spoke with a lilting Kenyan accent, and the way he delivered each line suggested that Charon could often barely contain the amusement he found in the unique position he held in this world of paid assassins.

The name Charon came from Greek mythology. Reddick getting to play Zeus in Percy Jackson felt like the logical next step in a career that had him playing increasingly powerful and influential men. It should not have been one of the final steps, though. Like many character actors who don’t fully come into their own until their forties, Reddick barely seemed to have aged at all since The Wire debuted. He seemed to have so many more years of giving us all that he had, and in making every character feel deserving of his innate, unmistakable talents.

He usually played the boss, but he was always the best boss.