Why I Chose to Appear in Netflix’s Controversial Pornhub Documentary

“Another day, another request to talk about Pornhub.” That’s what I thought when director Suzanne Hillinger and Oscar winner Alex Gibney’s Jigsaw Productions asked me to appear in their new Netflix documentary Money Shot: The Pornhub Story.

The film recounts how Pornhub exploded in popularity until The New York Times’s Nicholas Kristof and sex-trafficking victim advocates accused the streamer’s parent company, MindGeek, of hosting vile illegal child pornography and rape videos. Hillinger promised the film would show how right-wing Christians deployed sex-trafficking allegations as a Trojan horse to destroy the legal adult entertainment industry.

I was reluctant to sit down for an interview. Unless it’s a MILF porn set in a laundry room, I don’t typically air dirty laundry in public. And no disrespect to Hillinger, but I don’t trust documentary filmmakers. Most porn-world docs follow the Hot Girls Wanted model and present us as a bunch of manipulated, abused, low-IQ victims-cum-bimbos.

But more than anything, I was sick of talking about Pornhub. Since Kristof’s story ran, everyone from Vanity Fair to (ironically) The New York Times has asked me to discuss the scandal. I get it. I’m one of the most famous porn stars in America. I write about sex worker issues for news sites. But I’m over it. Personally, I do not care about Pornhub. I can’t be pressed to care about a streaming porn site because I don’t make the bulk of my money there. No one website is my bread and butter. If Pornhub goes under, seven thousand other tube sites will pop up. Who cares about a tube site?

The problem is that the war on Pornhub is a proxy war to take down the entire legal sex work industry. If Christians really cared about ending gross child porn, they’d go after Facebook, which hosts way more child sexual abuse material — 20.3 million reported incidents compared to 13,229 — than Pornhub or any of MindGeek’s tube sites ever has. But what they really want is to shut down Porn Valley.

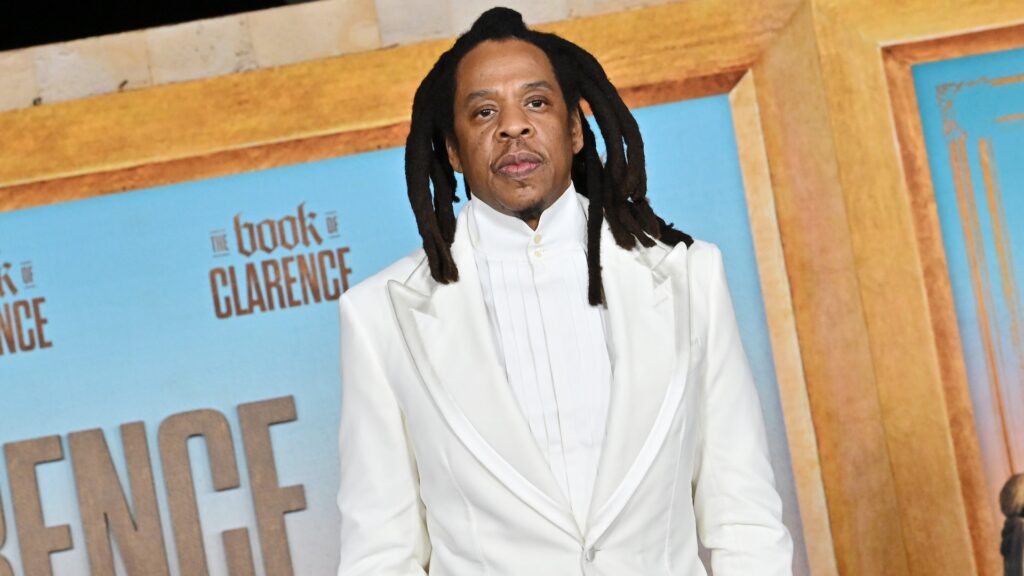

Siri Dahl in ‘Money Shot: The Pornhub Story.’

Netflix

I care about showing that anti-sex-trafficking campaigns are anti-porn campaigns in disguise. That’s why I started writing about these issues for news publications. That’s why I protest. If I didn’t speak up in the documentary, I worried nobody else would. Or even worse: They would find the dumbest porn star they could to present us as the stupidest women in America. So, I agreed to an interview.

For security purposes, I required Jigsaw to find another home for the interview. They rented a cottage somewhere in the hills around Los Angeles. It looked artsy, but as a content creator, I know cameras can pull tricks. They could have easily made me appear dumb, or like a bitch, so I purposefully covered up my skin. I also didn’t want them to make me look like a faker, so I made sure the colors were soft to avoid looking like I’d shown up for a deposition. I wanted to look friendly.

Over the course of the four-hour-plus-long interview, we discussed my time in porn, the evangelicals trying to destroy the legal porn industry, why I chose to start writing about the topic, and tons of other issues. They even filmed me typing on my laptop, working on an op-ed about sex work.

You won’t find much of this in Money Shot. Like several other porn stars, I appear as a talking head. The roughly 90-minute film tells an abbreviated history of Pornhub in chronological order. In a humorous, well-crafted way, the first act depicts the rise of Pornhub, from how it reached household-name status to the ubiquity of the brand’s theme song. They tell the tale through interviews with porn performers, recreations, and even some TikTok clips. It’s cute. They breeze through some crucial details (such as how MindGeek acquired Pornhub; it didn’t create it), but overall, it gets to the point.

The film, in my opinion, gets iffy in the second act. It introduces how sex-trafficking advocates at the right-wing religious organizations Exodus Cry and The National Center on Sexual Exploitation (NCOSE) became aware of Pornhub hosting illegal rape and child porn videos. NCOSE lawyer Dani Pinter tells the story on screen, but Exodus Cry’s cheerleader, Laila Mickelwait, declined an interview. Pinter sits in a suit in a corporate office, and they film her from a front angle. She’s intercut with experts from the tremendous non-profit the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which makes it seem like she’s associated with them, even though Pinter works for a radical Christian group.

Both Pinter and the NCMEC spokespeople describe horrific content on Pornhub. After Kristof becomes aware of the material, he publishes an expose in the Times, which leads to government investigations. Few people from MindGeek sat down for interviews, but we hear from two supposed MindGeek whistleblowers: a content moderator whose identity is disguised and a random human resources employee. The moderator makes serious accusations of MindGeek not taking down illicit material, but his disguise makes it hard for viewers to trust him. Furthermore, it’s unclear what the HR woman’s expertise or knowledge about MindGeek is.

The cinematographer shows these whistleblowers as brave individuals but shoots most porn stars, such as Asa Akira and me, from high angles. The camera slowly moves away from us, like we’re victims in a smut film. They give little context to differentiate us. For instance, Akira serves as a MindGeek spokesperson, and I’m an independent porn performer and writer, but we seem like we have identical backgrounds. If I didn’t know the girls on screen in real life, I would struggle to differentiate them. I’d also believe, from the victim angle — and from the film’s suggestion that we have to play ball with Pornhub for financial reasons, even though Pornhub is one of multiple platforms we can use — that we were coerced to defend Pornhub, even though most of us sat down to discuss how this war harms porn performers, not Pornhub.

Eventually, the movie cuts to the truth about the right-wingers. It details Mickelwait and Exodus Cry’s connections to a homophobic church. It shows how the lawyer who wants to derail MindGeek absurdly compares it to The Sopranos. Most vitally, it exposes how NCOSE was previously a Christian group called Morality in Media that was designed to end “immoral” content. It rebranded as NCOSE to capitalize on “sex trafficking” in order to end porn. When confronted, Pinter loses it on camera. It’s a great moment, exposing her as the con she is.

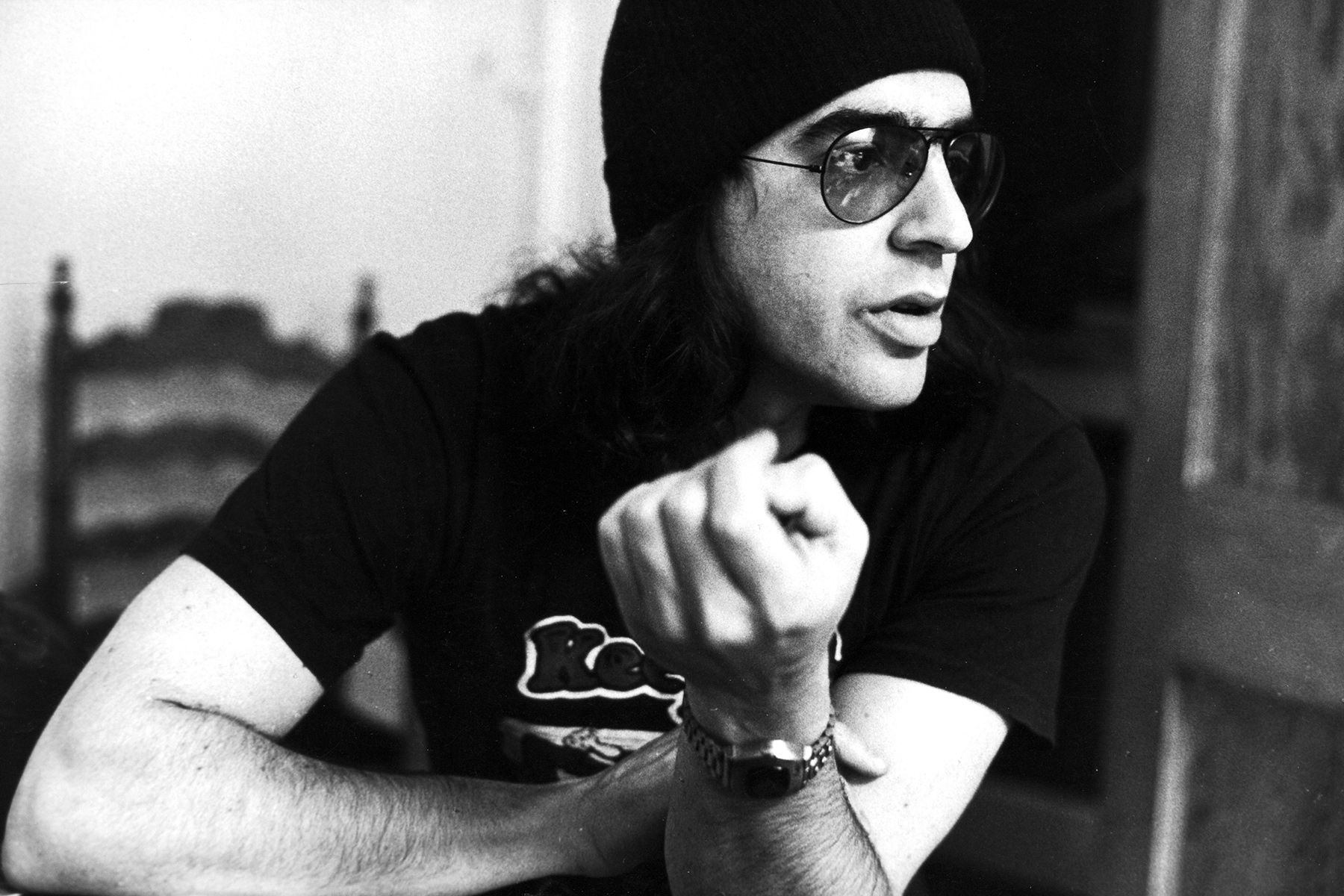

Cherie DeVille in ‘Money Shot: The Pornhub Story.’

Netflix

But the reveal comes so late it may confuse some viewers, mainly because the film never defines sex trafficking. Subjects repeat the phrase over and over. They say MindGeek was accused of sex trafficking, but without the definition, it sounds like the Times accused MindGeek executives of literally kidnapping children and filming them having sex. But nobody ever accused MindGeek of this. The Times accused MindGeek of hosting videos — which is still vile and wrong — but it’s very different from literally sex trafficking women and children.

The filmmakers wanted to support porn stars, but the sex-trafficking smear is so strong it’s hard for them to outright accuse the right wing of manipulating the public. Nobody wants to look like they support sex trafficking, so the film devolves into a “both sides” debate. The middle-ground approach makes it unclear what the film’s lesson is. Watching the film, I kept thinking about what President Donald Trump said about the horrific Charlottesville riots: “[There are] some very fine people on both sides.”

They could have solved this problem by editing the film differently. Instead of starting with Pornhub, begin with the evangelical extremists. If the directors showed the Christians’ motives from the get-go, starting with Exodus Cry’s origins and NCOSE’s rebrand, there wouldn’t be ambiguity. It would be clear that Pornhub hosted horrible videos, but this is a problem across the internet, and these right-wingers are using “sex trafficking” to destroy porn.

I didn’t hate Money Shot. I didn’t love it. But the film would be worse if other sex workers and I didn’t participate in the film. It lacked a narrator, so the movie depended on the testimony of those who sat down on camera. The more porn performers talk to the press, the more likely journalists and directors will share our lived experiences instead of the fabricated talking points of self-proclaimed “sex trafficking advocates.”

Two “advocates” not tweeting about the film are Dani Pinter and Laila Mickelwait. And if two of America’s most self-righteous, Twitter-addicted attention-seekers aren’t tweeting about Money Shot, then they believe the documentary hinders their cause. A problem for Mickelwait is the perseverance of the sex workers’ rights movement. Money Shot wasn’t perfect, but it will stream on a major platform, where it will further dent the false narrative about the porn industry. For that reason, I’m ultimately grateful I spoke in Money Shot. And I won’t stop speaking up.