We’re Told Never to Meet Our Childhood Heroes. Knowing Daniel Ellsberg Proved That Wrong

That you should never meet your heroes, as they are bound to disappoint you, has become such conventional wisdom that it requires no author to affirm it. In a 2020 satirical New Yorker article, Alex Witt attributed the proverb to the faceless “they” (“They say, ‘Never meet your heroes,’ ” adding, “It’s good advice. I’ve met all of my idols, and I’ve been disappointed by every single one”). Some internet pages attribute the quote to the British comedian Alan Carr after meeting Paul Newman, though that appears more apocryphal than reliable. It hardly matters who first said it; it just strikes one as intuitively true because the glaring, multifaceted imperfections of humans when seen up close make a heroic image unlikely to survive interpersonal scrutiny.

Daniel Ellsberg, the renowned Pentagon Papers whistleblower, single-handedly destroyed the validity of this advice for me. Ellsberg was one of my two or three top childhood heroes. Though I was only four years old in 1971, when he knowingly assumed a high probability of life in prison to inform the American people about systemic lying by the U.S. government regarding the war in Vietnam, I became engrossed by both the Pentagon Papers and Watergate dramas as I entered adolescence. Those became the formative events for my understanding of politics and journalism.

The lies told by leading Pentagon and CIA officials about the Vietnam War were numerous, and they came fast and furious from the start of the U.S. role in the war in the early 1960s to its end in the mid-1970s. The lie that led Ellsberg to risk his liberty to expose was central. Top Pentagon and other U.S. security-state officials were publicly insisting they were getting closer and closer to winning the war, all while privately admitting from the start that victory would be impossible, that the best-case scenario was a stalemate with the North Vietnamese.

Ellsberg’s remarkable moral courage and self-sacrifice to try to stop an unjust war from spirling even further out of control played a major role in shaping my understanding of journalism, the need for transparency, the virtues of bravery, and the duties of citizenship. I read everything I could get my hands on about Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers case. That someone at the age of 40 would be willing to spend the rest of his life in prison for a political cause both mystified and excited me. Ellsberg occupied a central place in my childhood imagination about heroism, integrity, and courage.

That is the context that led to Ellsberg’s destruction for me of the wisdom of this “don’t meet your heroes” aphorism. One of the greatest honors of my life was developing a long and multifaceted relationship with Ellsberg: first meeting him (in 2008), then spending years forming a friendship with him, and then working at his side.

I was beyond nervous to meet Ellsberg. Like a junior high student meeting their favorite pop star, I began inarticulately spewing my longtime admiration for him. But he quickly intervened to say that he often felt more shame than pride about the Pentagon Papers: not because he regrets divulging those top-secret documents but because it took him as long as it did for him to find the courage to leak them. He told me that to this day, decades later, he thinks often about how many people died — Americans and Vietnamese — while he was helping plan and advocate the war at RAND Corp., and how pained he is over the fact that he could have acted earlier to try to stop that loss of life.

We’re talking about someone who came very close to spending his life in prison for the act of conscience he undertook: a level of courage most people cannot get close to. Yet it was so clear to me, and it genuinely shocked me, that he imposed on himself this moral burden to have acted even earlier.

In 2012, we co-founded an advocacy group for journalists, the Freedom of the Press Foundation (FPF). The group, which now engages in broad-based press-freedom activism, was originally designed to circumvent the ban on financial services imposed on WikiLeaks, at the urging of senior U.S. officials, by Bank of America, MasterCard, Visa, Amazon, and others, all despite the fact that WikiLeaks had never been charged with, let alone convicted of, any crime.

The creation of this group was far from risk-free: We decided we would collect funds and donations on WikiLeaks’ behalf in order to destroy the ability of the U.S. government and large banks to effectively crush dissident media outlets by imposing extrajudicial bans on their ability to collect funds. There was a legal concern that by helping sustain WikiLeaks financially, we could be held accountable for future criminal accusations against it.

Our initial goal was to make the FPF a model for how similar future attacks on media outlets could be defeated. Along with Laura Poitras, the Oscar-winning director of CitizenFour and my journalistic colleague in the Edward Snowden reporting, various privacy activists, the actor John Cusack, and ultimately Snowden, Ellsberg became a co-founder and joined our board.

Daniel Ellsberg, former United States military analyst considered the Pentagon Papers whistleblower, speaks during mass rally in support for PFC Bradley Manning in June 2013 in Fort Meade, Maryland, just before Manning’s court martial was set to begin. Hundreds of supporters marched in support of Manning for giving classified documents to the anti-secrecy groups including WikiLeaks.

Lexey Swall/Getty Images

As was true with the Pentagon Papers disclosures and in many other instances in his life, Ellsberg never once expressed hesitation due to the risks involved. The contrary was true: As we were forming this organization, he often gave rousing speeches about the imperative of political courage precisely when the state becomes most repressive.

He was continuously a source of inspiration for all of us. We often spent hours in meetings of our board, composed of famously wilful people with strong opinions, which often diverged from one another. During even intense debates, Ellsberg was not only a voice of inspiration but a voice of reason and decency, constantly reminding us that we all shared the same vision and the same goals and, leading by example, urged that we treat one another with compassion and kindness even when we vehemently disagreed.

In sum, the more I got to know Ellsberg as a person rather than as an icon, the more my respect, affection, and love for him grew. The image I had of him from his Pentagon Papers fame was exactly what motivated the way he conducted himself in life — from how he formed his political ideals to how he treated others. There was never a moment in the many hours we spent in conversation, either personally or during the years of FPF board meetings, where I detected any false notes let alone felt “disappointed” in him. That includes the rare occasions when we found ourselves on different sides of internal debates, and on the less-rare instances where we harbored disparate political views. He was unfailingly polite even when emphatic, always guided by immoveable principles that he was unwilling to compromise for any strategic or material gain yet was always free of personal rancor, and was one of the most deeply knowledgeable persons with whom I have ever conversed. As a human being, he personified the values I had associated in childhood with the Pentagon Papers.

What most defined my impressions of Ellsberg was his extreme humility. When Ellsberg was first identified as the Pentagon Papers leaker, he was maligned in establishment circles with the same set of accusatory labels automatically applied to those who expose the secrets of America’s most powerful actors: as a traitor, a Kremlin agent, and someone who had placed Americans in danger. Yet Americans’ views in the ensuing decades have become far more negative about the Vietnam War and he has, in the eyes of millions, become vindicated. By the time we first met, in Washington, he knew that millions of people around the world, such as myself, regarded him as a hero, but was very uncomfortable with that label. It was not the kind of false humility that many similarly admired people wear as self-glorifying costume, but one he deeply felt.

Every time I heard someone placing the hero label on him, he quickly acted to dilute it by pointing out what he believed was the responsibility he bore for the war: both in the early stages when he was helping to execute it and then in the later stages, by which point he had turned against it (even attending anti-war rallied while still employed at RAND), but not yet willing to risk his liberty to bring the truth to the public.

The torment from having to spend the rest of his life knowing that he had yet refused the opportunity to show the truth and help end this war — all due to his fear of what would happen to him — was far greater than whatever punishments he would suffer for disclosing the truth, even if that meant life in prison.

Ellsberg was aggressively generous with the use of his hero status to defend others whom he viewed as motivated by the same values and objectives that caused him to disclose the Pentagon Papers. I vividly recall how viscerally happy and moved he was when the next generation of courageous whistleblowers began appearing: WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange; U.S. Army Private Chelsea Manning, who leaked to WikiLeaks; NSA whistleblowers Edward Snowden, Tom Drake, William Binney, and others. He would never take credit for them or their bravery, but it was clear that he saw them as his progeny.

He often said in private what he ended up saying in the media about all of them: that he had waited decades for people like them to appear; those who had access to secrets that would both expose the lies and corruption of the U.S. Security State but which would also end their careers and reputations, if not land them in prison, for disclosing them. Ellsberg’s tireless commitment to the FPF, even while he was already in his 80s, was motivated by his sense of obligation to use his credibility to defend what Assange and Manning had done. He viewed his battle with the secrecy abuses and systemic deceit of the military and intelligence communities as his life mission, and he never stopped pursuing it with a vigor and commitment to study that would tire most people half his age.

In both instances in which I found myself in the middle of highly dangerous reporting where prison was a possibility not only for my whistleblowing source but also myself and my journalistic colleagues — the 2013 Snowden reporting and the 2020 Brazil exposés that freed Brazilian President Lula da Silva from prison — Ellsberg spent many hours of his time encouraging me, offering advice, and urging me to press forward despite various risks and threats. In emails he shared with me and other FPF board members after we learned in June 2013 that Snowden had been quickly charged with multiple felonies, he wrote:

Same charges as against me, forty years ago … His case will test the question: Can it be criminal (as 18 U.S.C. 798 clearly states) to disclose classified information [about communications intelligence processes, when] that hides what appears to be a blatantly unconstitutional program? That’s never been tested before in an American court.

At one particularly stressful moment when I was in Hong Kong with Snowden and Poitras — when my lawyers were receiving increasingly menacing threats about our possible criminal prosecution from DOJ lawyers if we tried to return to the U.S. — Ellsberg spent an hour on the phone with me urging me to see that not as an impediment but an opportunity. While he was of course happy not to spend his life in prison for the Pentagon Papers, he regretted the fact that he lost the opportunity to win a vital precedent against the U.S. government when his charges were dismissed due to government misconduct.

He urged me to press forward without concern for any such intimidation, and to see the prospect of criminal prosecution as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to fight the DOJ over constitutional guarantees of press freedom. That Ellsberg was fortifying my resolve, and doing so by invoking the values of courage and a willingness to risk one’s own interests for a noble cause, was an honor, personally moving, and — along with Snowden’s own self-assured bravery — undoubtedly one of the things I used to continue regardless of the risks.

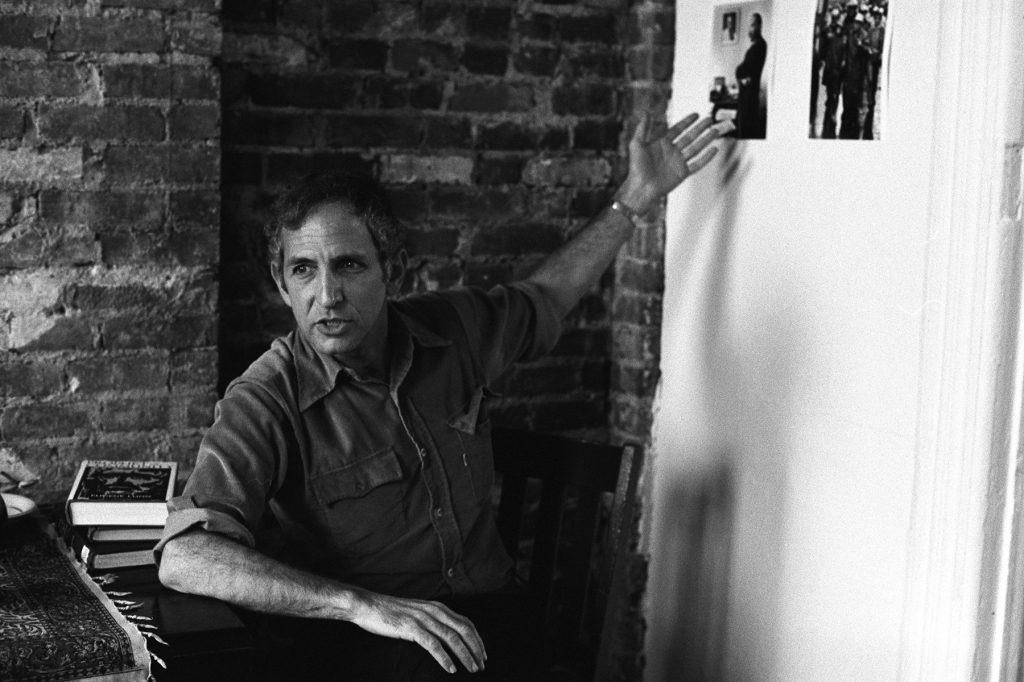

Military analyst and political activist Daniel Ellsberg gestures towards a picture on a wall in October 1976. Ellsberg was the source of the leak of the controversial Pentagon Papers, a goverment document about the decision-making process during the Vietnam War.

Susan Wood/Getty Images

I’ve had the opportunity to meet and get to know many people who are renown for a political or journalistic act that inspires admiration. Often, it is not always evident how the values with which they are publicly associated end up shaping their private conduct. With Ellsberg, the exact opposite was true: The ethics and morals that drove him to leak the Pentagon Papers were visible in how he treated others.

At our board meetings, he was always the voice of harmony. In private conversations, he emphasized the love and human connection that he believed our politics should foster: He ended every email with “Love, Dan” and was as inspiring talking about personal challenges as he was about political or journalistic ones. It was humanistic impulses that led him to leak the Pentagon Papers — the belief that human beings were dying in large number for no good reason and that he had the moral obligation to do what he could to stop it — and he was never shy about expressing that humanism in his interpersonal dealings.

The authenticity of his convictions were never in doubt: Despite being someone situated on the left wing of American politics, he was scathing in his critiques of President Obama’s unprecedented attacks on whistleblowers. Having believed in Obama’s 2007-08 vows to uproot the core precepts of the War on Terror, he viewed Obama’s strengthening of those precepts as a betrayal: not only of Ellberg’s trust but of Obama’s core oath of office.

And there were few things that Ellsberg took more seriously, if there were any, than oaths of office. His core defense of the Pentagon Papers leak was that he was not just permitted but obliged to disclose these documents by the oath he had taken. “Daniel Ellsberg: Snowden Kept His Oath Better Than Anyone in the NSA,” read an Atlantic headline in 2014. Ellsberg took oaths very seriously. They were his supreme moral compass, and when he used it to tell you that he thought you were doing the right thing, few things were more gratifying and emboldening.

Despite his decades of activism, Ellsberg’s obituaries will all lead with the role he played in the Pentagon Papers leak and the political and journalistic drama that arose in its wake. That is understandable. What he did then was as consequential as it was courageous.

What made him so rare as a dissident was that his life was paved with establishment credentials and accolades, which he could have easily spent his life exploiting for his own personal gain. With a Ph.D. from Harvard and a Wilson fellowship at Cambridge, he joined the Marine Corps and rose to the rank of lieutenant. In the late 1950s, Ellsberg went to work for the RAND Corp., the think tank widely regarded as the Pentagon’s closest and most trusted nongovernment partner. He focused on nuclear strategy and the nuclear arsenal, which placed him at the center of the most vital and sensitive Cold War policy-making debates. That necessitated his holding the highest security clearances the U.S. government has to offer (he often regaled us with fascinating explanations of the numerous secrecy classifications far above “top secret”).

By the time he was 35, Ellsberg had risen to the highest level of Pentagon war planning and design of nuclear weapons doctrine. There was no limit on his ability to rise even further within the halls of government, academia, or corporate power centers. And that is what makes his decision to purposely throw all of that away — trading unlimited material prosperity and establishment esteem for decades in a federal prison cell, all for a cause, all to save the lives of others. It was an act at once so remarkable, so admirable, so rare, and so stunningly and singularly self-sacrificing.

“How can you measure the jeopardy I’m in … to the penalty that has been paid already by 50,000 American families and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese families? It would be utterly presumptuous of me to pity myself, and I do not.”

Daniel Ellsberg

Due precisely to his access to the government’s most secretive documents, Ellsberg — who began as an ardent advocate and key planner of the war in Vietnam — began turning against it several years before he catapulted himself to fame and to the top of the Nixon administration’s enemies list. He concluded that the war — and especially the annual deaths of thousands of America’s conscripted soldiers and the tens or hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese civilians — was based entirely on lies.

It was a lie that launched the start of the U.S.’ full-scale role in war. The story told by the Pentagon and the CIA about North Vietnamese aggression against American ships in the Gulf of Tonkin, off the Vietnamese shore, led the U.S. Senate to approve by a near-unanimous vote the authorization of military force, in August 1964. Yet even the U.S. Naval Institute now acknowledges, based on declassified documents, that “high government officials distorted facts and deceived the American public about events that led to full U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.” In his book expressing regret for the role he played in prosecuting the war, the then-Defense Secretary, Robert S. McNamara, branded those war-starting claims about the Gulf of Tonkin incident: “LIES.”

As the war dragged on year after year, and more and more Americans and Vietnamese were dying, Ellsberg came to believe that the U.S. Security State did not only spread falsehoods through the corporate media to justify the start of the war (exactly as they would do again 38 years later to justify the invasion of Iraq). After the Gulf of Tonkin deceit, the prosecution of the Vietnam War was continuously fueled by and based in a massive lie: Namely, America’s top political and military leadership knew they could never win the war, and continuously acknowledged that in top-secret studies. Yet while producing study after study demonstrating the war’s futility, these same leaders repeatedly told Americans the exact opposite — that victory was just around the corner as long as they supported greater expenditures, more weapons, and drafted more and more young Americans to be sent to fight in the jungles of Vietnam.

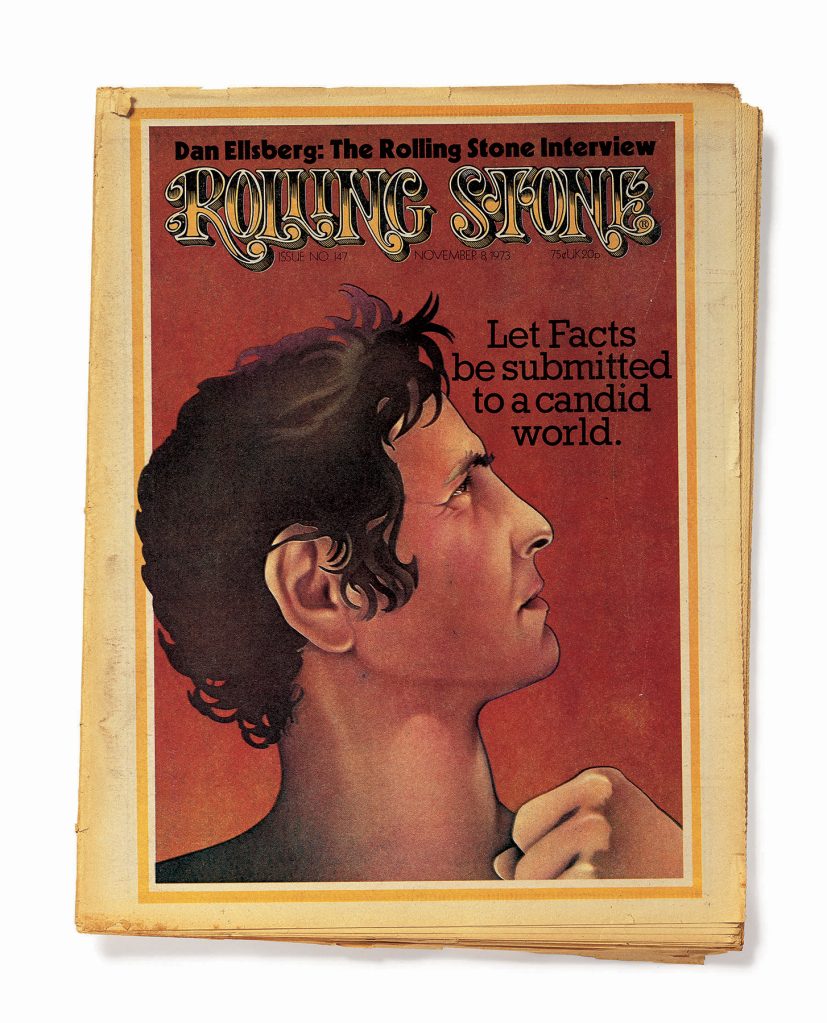

The Nov. 8, 1973, issue of “Rolling Stone”

Illustration by Dave Willardson

As he heard one American leader after the next disseminate these lies through a largely uncritical media, Ellsberg knew he had the documents in his hands that would dispositively reveal these lies to the American population, which had been deceived into believing them. Ellsberg had participated in the creation of multi-volume studies, and he had access to many others that all reached the same conclusion.

The problem he faced: The truth-revealing documents were, as they so often are in Washington, marked “top secret,” which meant anyone disclosing them to those unauthorized to receive them (i.e., the press and public) would be guilty of felonies — among the gravest felonies in the U.S. Code. Many of those felonies were created by the 1917 Espionage Act, first enacted under President Woodraw Wilson to criminalize opposition to the U.S. role in World War I.

Ellsberg decided that he had no choice. The torment from having to spend the rest of his life knowing that he had yet refused the opportunity to show the truth and help end this war — all due to his fear of what would happen to him — was far greater than whatever punishments he would suffer for disclosing the truth, even if that meant life in prison. He first attempted to persuade U.S. Senators to read the Pentagon Papers on the floor of the Senate; despite the fact that the U.S. Constitution immunizes them from any consequences for speeches on the floor, none would do so.

Ellsberg then proceeded to use Xerox machines — there were no such things back then like CDs, let alone thumb drives — to secretly create multiple sets of what became the Pentagon Papers: thousands of pages of top-secret documents about the Vietnam War assembled at the highest levels of the government to which he had been granted unfettered access. It took him eight months to copy each page one by one using a single Xerox machine in a friend’s office. He delivered a copy to The New York Times. On Sunday, July 13, 1971, the paper began publishing reports and original documents that it called the Pentagon Papers.

To say that this caused panic inside the U.S. government is to understate the case. Within days of the first article, the Nixon administration persuaded a federal court to restrain The New York Times from further publication, the first-ever act of prior restraint in the nation’s history. So determined was Ellsberg to ensure that Americans would see these documents that, after this court order restraining the Times, he then sent thousands of pages to The Washington Post. When the Post began publishing, the Nixon administration sought to restrain that paper as well, but a different court ruled in the Post’s favor. To make the censorship effort more difficult, if not impossible, Ellsberg sent copies to numerous other newspapers, and then persuaded Sen. Mike Gravel (D-AK) to begin reading parts of it on the Senate floor.

The conflicts in the judicial rulings led the Supreme Court to quickly take up the case. It resolved the question in its landmark 6-3 ruling that became known in New York Times v. Sullivan, viewed as one of the most significant press freedom decisions in American history. The court explicitly noted that it was not deciding the question of whether the newspapers themselves violated the law and could be ultimately prosecuted. The ruling was confined solely to the question of prior restraint. And there, the Court emphatically ruled that “every moment’s continuance of the injunctions against these newspapers amounts to a flagrant, indefensible, and continuing violation of the First Amendment.”

Ellsberg never intended to conceal his identity as the leaker by hiding behind journalistic anonymity. To the contrary, he viewed his willingness to come forward, voluntarily identify himself, and explain his rationale to the American people to be at least as important as the Pentagon Papers themselves. He viewed his ability to argue to the American people why his actions were not only justified but morally obligatory — both prior to his trial and at the trial on the stand — as a crucial opportunity to convince Americans that the Vietnam War was immoral and based on lies. He evaded the FBI manhunt just long enough to ensure publication. And then, already indicted for 12 felony counts including violations of the Espionage Act, he turned himself in.

Daniel Ellsberg and wife walk from court right after a federal judge just dismissed the Pentagon Papers case against him.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

At the federal building in Boston where he turned himself in, he was asked by a journalist whether he regretted what he did given that he now faced multiple felony charges and a 115-year prison term sought by the government. His reply: “How can you measure the jeopardy I’m in … to the penalty that has been paid already by 50,000 American families and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese families? It would be utterly presumptuous of me to pity myself, and I do not.”

Ellsberg presumed that leaking the Pentagon Papers would not only subject him to criminal prosecution but also attempted character assassination. He was most certainly right about that. The government’s attempts to attack and malign Ellsberg were malicious and deranged — so much so that they are what saved him from life in prison.

Several Nixon White House officials, including John Ehrlichman and Henry Kissinger, attempted — invoking a tactic well familiar to Americans now — to suggest he was a Kremlin agent. A 1971 memo about Ellsberg written by Howard Hunt, a former CIA officer who ended up at the Nixon White House, where he later played a major role in the break-in of the Democratic National Committee that led to the Watergate scandal, was leaked to The New York Times.

In it, Hunt argued that the best way to destroy Ellsberg’s reputation and thus distract attention from the revelations of the government lying about the war would be to tie Ellsberg to Moscow in the public’s imagination (sound familiar?). Hunt reasoned that while there was no evidence to substantiate the accusation, they should publicly emphasize that “the distinct possibility remains that Ellsberg’s ‘higher order’ [which he said outweighed his duty to obey the law by keeping the Pentagon Papers concealed] will one day be revealed as the Soviet Fatherland.” The former CIA operative also argued — in reasoning often used today — that “the leaders of North Vietnam, Red China, and the Soviet Union were the undoubted beneficiaries of Ellsberg’s revelations,” they could convince Americans that his intentions were not a noble desire to inform Americans but rather a treasonous attempt to strengthen America’s enemies.

But the most twisted attack on Ellsberg was one so shocking to the conscience that it caused the federal judge to dismiss the criminal case against him. This plot came from a group of former CIA and FBI agents working in the Nixon White House as the so-called “Plumbers” (to deal with leaks). They orchestrated a break-in into the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in order to discover Ellsberg’s sexual proclivities and other psychosexual secrets. When first learning about the Pentagon Papers, I recall struggling for years trying to understand why Nixon officials would believe that revelations about Ellsberg’s sexual fantasies and sex life would effectively undermine the proof offered by the Pentagon Papers of deliberate government deceit. It seemed like the ultimate non sequitur.

From a strictly logical framework, it was. But these veteran intelligence agency operatives had been around Washington for decades, and knew that nothing destroys one’s reputation like a sex scandal, or anything of a sexual nature that makes a person so distasteful in the eyes of the public that they want nothing to do with anything relating to them. If a person is seen as sufficiently tawdry and strange, then the public temptation is to simply turn away from anything the person has to offer.

That is why it is so common in Washington for scandals about a person’s private life or innuendo about their sexual proclivities to be weaponized to discredit their revelations and other arguments. It may not be logical, but it is a form of character assassination that plays on our natural instincts for tribal acceptance and societal conformity. The White House Plumbers were masters of the political dark arts, and Ellsberg, himself having spent more than a decade at the highest levels of institutional power, knew that the attacks he would endure would extend far beyond purely legal ones.

His moral courage and tireless commitment to exposing the corruption and systemic deceit of the U.S. Security State never even slowed down as he entered his nineties.

The burglars did succeed in finding at least one of Ellsberg’s psychiatric files, but it contained few valuable revelations to support a smear campaign. The former CIA officials became convinced that the real dirt on Ellsberg was at the psychiatrist’s house, but White House counsel John Dean refused to approve of the second break-in.

But this dirtiest of dirty tricks proved highly consequential. It became the precursor to the Watergate break-in nine months later. And it played a major role in the ruling by Ellberg’s judge to dismiss the prosecution of him on the grounds of governmental misconduct (the government had also illegally wiretapped Ellsberg’s calls). Absent that break-in, there is a high likelihood that Ellsberg, who had admitted leaking the Pentagon Papers, would have spent decades if not his entire life behind bars.

Ellsberg’s primary plan at trial was to argue to his jury that his leaking the Pentagon Papers was justified and morally necessary even if it were illegal. But that plan was quickly destroyed when the judge, during Ellsberg’s testimony, ruled that no such defense can be raised under the Espionage Act. Every time Ellsberg attempted to argue that he was morally justified in leaking these documents, the judge would interject before he could speak more than a few words and order him to stop.

That adverse ruling — that the 1917 Espionage Act is a strict liability statute that requires conviction as long as an unauthorized leak can be proven, and that no “justification” defense or any other arguments about motive is permitted — led to an explosion of the use of this statute in the decades that followed. That blast reached its maximum radius in the 2010s, when President Obama oversaw the prosecution of eight whistleblowers under this law — more than all previous presidents combined.

In 2013, the Obama DOJ brought charges under this 1917 law against NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden. While attempting to flee to South American to obtain asylum, Snowden was trapped by Obama officials in Russia, after they invalidated his passport and coerced the Cubans into withdrawing their guarantee of safe passage. Leaders of both parties dared Snowden to come back to the U.S. Then-Secretary of State John Kerry said Snowden should “man up” and argue to a jury of his American peers that he was justified in leaking the surveillance behemoth’s secrets. But Snowden knew, because of Ellsberg’s example, raising such a defense was impossible. He saw how Ellsberg was silenced at his trial every time he attempted to explain his actions. Under that 1917 law, no such defense of whistleblowers is permitted.

For that reason, Ellsberg was scathing of Obama’s attacks on whistleblowers such as Snowden and Manning. He told The Washington Post in a 2013 interview that one of his secondary motives for leaking the Pentagon Papers was “the hope of changing the tolerance of executive secrecy that had grown up over the last quarter of a century both in Congress and the courts and in the public at large.” While he believes that the Pentagon Papers and the subsequent Watergate scandal partially ushered in reforms, he told the Post that most of those reforms designed to prevent the U.S. Security State from abusing its secrecy powers and lying to the American public had crumbled, especially in the wake of 9/11 and the War on Terror.

Ellsberg assigned a significant amount of blame to President Obama for aggressively eroding many of those reforms. He argued in that interview that Obama’s Attorney General, Eric Holder, should have been fired for illegally spying on numerous journalists including Fox News’ James Rosen. Holder’s firing, Ellsberg said, would be a “first step of resistance in the right direction, of rolling back Obama’s campaign against journalism, freedom of the press in national security.” And he scoffed at the idea that Obama was any better than Nixon when it came to press freedoms: “I’m sure that President Obama would have sought a life sentence in my case,” he said. The interview itself was centered on Ellsberg’s vocal defense of Chelsea Manning, who provided tens of thousands of classified documents to WikiLeaks.

Indeed, in all of Ellsberg’s actions and statements, one can find the hallmarks and motives of the next generation’s most famous and consequential whistleblowers and secret-spillers: Assange, Snowden, and Manning, who spent seven years in a military prison for exposing the inner workings of the American war machine in Afghanistan and Iraq and the corruption of other regimes around the world. There is little doubt that most if not all of them were inspired, directly or indirectly, by him. And it thus makes complete sense that Ellsberg regarded that trio in particular as his heroes, and spent the past decade of his life acting as their most vocal and steadfast defenders.

Ellsberg said Snowden, by knowingly risking life in prison to prove that senior Obama officials had lied about NSA spying, “show[ed] the kind of courage that we expect of people on the battlefield.” When Snowden’s critics tried to use Ellsberg to attack Snowden’s decision to leave the U.S. rather than stay to fight, Ellsberg penned an op-ed for The Washington Post headlined: “Snowden made the right call when he fled the U.S.” He argued that — unlike during the time when he leaked, when he was out on bail and was able to defend himself publicly in the media — those accused of national security crimes in the U.S. are now, even before trial, immediately imprisoned, held incommunicado, and treated like terrorists before they are found guilty:

APR 1978; Daniel Ellsberg Prepares to Join the Sit-in Group; He referred to Rocky Flats Production as “a movable holocaust.”

Lyn Alweis/The Denver Post/Getty Images

I hope Snowden’s revelations will spark a movement to rescue our democracy, but he could not be part of that movement had he stayed here. There is zero chance that he would be allowed out on bail if he returned now and close to no chance that, had he not left the country, he would have been granted bail. Instead, he would be in a prison cell likeManning, incommunicado.

Ellsberg similarly championed Assange, testifying in his defense in Assange’s U.K. extradition hearing in 2020 that Assange and Ellsberg’s actions were identical. He insisted that the WikiLeaks founder “cannot get a fair trial for what he has done under these charges in the United States.”

While Assange has always been in a different position from the other three — given that he never worked for the U.S. government and thus had no legal obligation to maintain its secrets — Ellsberg always said he saw the four of them as kindred spirits. What united all of them, in his view, was that they faced the same adversary (a U.S. Security State that chronically abuses it secrecy powers to lie to the American people); were confronted with the same dilemma (holding the proof of those lies in their hands but knowing that the proof had been classified in such a way as to make disclosure by them a likely felony); and ultimately all made the same remarkably courageous and self-sacrificing choice (knowingly risking life in prison, to no profit for themselves, in order to allow their fellow citizens to learn the truth about what the government is doing in the dark and in their name).

Snowden told me in our very first conversation that he refused to remain anonymous after leaking NSA documents, and that instead he felt it was his moral duty to voluntarily identify himself and explain to the public his reasons for revealing the truth. As I struggled in that Hong Kong hotel room to understand why someone at the age of 29 was willing to go to prison for decades in order to reveal the truth — the outcome that was by far Snowden’s likeliest outcome, as he well knew — the only instrument I could find for understanding self-sacrifice of that magnitude was Daniel Ellsberg.

That someone at the age of 40 would be willing to spend the rest of his life in prison for a political cause both mystified and excited me. Ellsberg occupied a central place in my childhood imagination about heroism, integrity, and courage.

When Snowden told me that he could not live with himself if he knew he had the power to stop indiscriminate, secret, and unconstitutional NSA spying but was too scared to do so, one could hear the echoes of Ellsberg’s own explanation for his choice. And when I heard exactly the same retrospective resolve, expressed in the same unflinching ethical certainty, when speaking with Julian Assange and Chelsea Manning, I immediately recognized its genesis.

The Pentagon Papers were so historically significant, and the aggressive courage of Ellsberg was so striking, that it will likely obscure many of his other consequential accomplishments. Last month, I interviewed the longtime Harvard economist and Washington insider-turned-dissident Jeffrey Sachs, and he admiringly mentioned Ellsberg’s work several times, none of which was related to the Pentagon Papers.

That included Ellsberg’s dare in 2021 for the U.S. government to arrest him. In an attempt to warn Americans of the dangers of the U.S. role in Ukraine, which he vehemently opposed, Ellsberg released a top-secret document showing that the U.S. had intended in 1958 to launch a first-strike nuclear attack against China after it had seized several islands off the coast of Taiwan. He viewed the risk of nuclear confrontation from the war in Ukraine — an ever-escalating proxy war between the two nations with the world’s largest nuclear stockpiles — as disturbingly high. He wanted to remind Americans that nuclear war is not some unthinkable, borderline-impossible outcome but one that has very realistically been considered many times during the Cold War, a species-terminating disaster that remains very present as long as countries remain nuclear-armed and engaged in conflicts.

Given that the document had never been declassified, Ellsberg insisted that what he did was no different from what Assange, Manning, and Snowden had done, and wanted to be prosecuted under the Espionage Act at the age of 90 to highlight the injustices of those prosecutions. He was daring — even urging — the U.S. government to prosecute him under the same theories it is using for Assange and Snowden. Sachs also cited Ellsberg’s 2017 book, The Doomsday Machine, as one of the most important historical accounts of the U.S. nuclear program by someone who helped design it, all as a way of highlighting the very real and ongoing dangers of nuclear war.

Ellsberg may have been most famous for his wilful defiance and dramatic encounter with the U.S. government 52 years ago. But his moral courage and tireless commitment to exposing the corruption and systemic deceit of the U.S. Security State never even slowed down as he entered his nineties.

I would listen to him for hours explicate with such precision and perfect memory the intricacies of nuclear policy from the 1960s, or be inspired as he urged us to take significant risks in pursuit of what he saw as just, or watched as he continued his tireless work in the same exact spirit that motivated the Pentagon Papers leak and his unblinking willingness to go to prison for it. As I did, I felt nothing but gratitude that I was able to meet my hero, and awe over the rich layers of his character, moral courage and heroism that I could not possibly have known had he remained an abstraction or an image for me.

One might assume that someone who came very close to spend the rest of their life behind bars – saved only by the particularly egregious conduct of the government they sought to expose – would harbor at least some doubt, some regret about their choice. Ellsberg did have one misgiving. It was this: “My one regret, a growing regret really, is that I didn’t release those documents much earlier when I think they would have been much more effective.”