The Timeless Glam Perfection of T. Rex: Why Marc Bolan Still Casts a Spell

Bang a gong, fans. The great British glam-rock studs are finally going into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, a year after their comrades Roxy Music. It’s a beautiful moment because has always stood for everything benignly insane about glam. T. Rex didn’t flourish long — Bolan was killed in a car crash in 1977, just two weeks shy of his 30th birthday, and wrote nearly all his great songs in a three-year hot streak. But he’s been a guiding spirit for cosmic dancers ever since. In “Spaceball Ricochet,” he sang, “Deep in my heart, there’s a house that can hold just about all of youuuus.” That house is still a wild and inviting place to visit, which is why T. Rex still matters today.

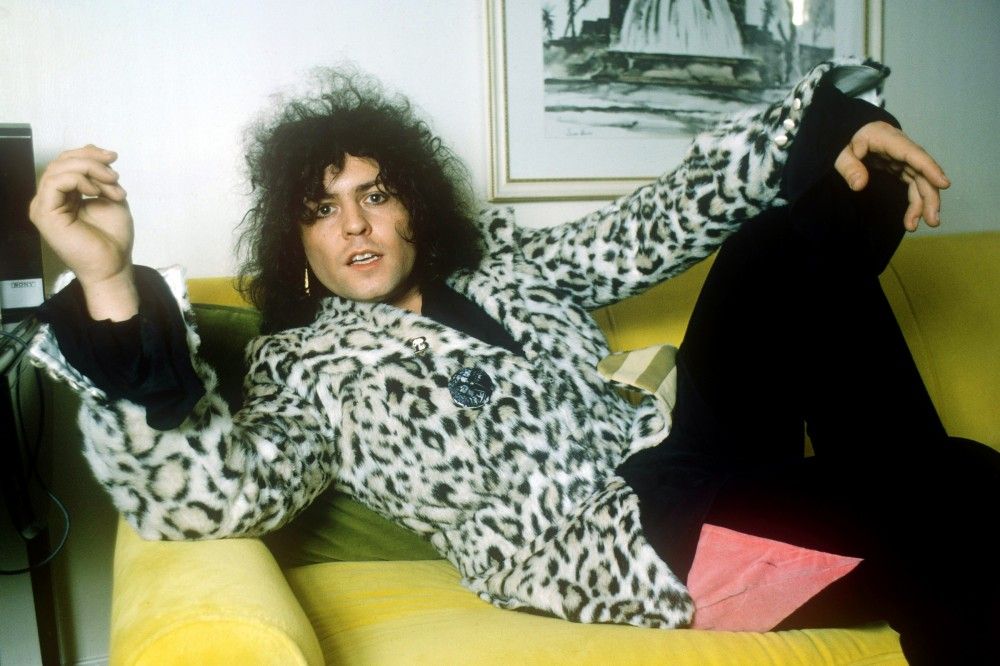

Rex ruled the U.K. charts in the early Seventies, led by Bolan’s fey vocals and shameless egomania. As he explained in his 1972 Rolling Stone cover story, “T. Rex is a monster. And I’m the whipmaster.” He was glitter rock’s prettiest boy-child, an androgynous prince strumming his Les Paul under the mambo sun and living out his silver-studded saber-tooth dreams with his tribe of mystic ladies. He made two perfect albums, 1971’s Electric Warrior and 1972’s The Slider, with a personal philosophy that was basically “I got stars in my beard and I feel real weird.”

Even though T. Rex were often dismissed as bubblegum pop, they’ve always cast a spell over music weirdos. Prince had a Number Two hit with his 1985 tribute “Raspberry Beret,” and reached Number One with the even more blatant “Cream.” The Smiths ripped off the “Metal Guru” riff for “Panic.” Bolan invented Slash’s look, with a top hat on his corkscrew hair; Guns N Roses repaid the debt by covering “Buick MacKane” on their 1993 album The Spaghetti Incident. Just last summer, when Harry Styles was making his extremely Bolan-esque pop gem Fine Line, he brought in a string quartet for the song “Treat People With Kindness.” He played them T. Rex’s “Cosmic Dancer” over the stereo speakers to show the vibe he was hoping for. “Yeah, it’s pretty T. Rex,” Harry said after one take. “Best damn strings I ever heard.”

Part of the Bolan mystique: He had more vanity per square inch than any rock star ever. “I’ve always been a wriggler,” he boasted to Record Mirror in 1971. “I mean, I am my own fantasy. I am the ‘Cosmic Dancer’ who dances his way out of the womb and into the tomb on Electric Warrior. I’m not frightened to get up there and groove in front of six million people on TV because it doesn’t look cool. That’s the way I would do it at home. It’s not serious. I’m serious about the music but I’m not serious about the fantasy.”

Born in 1947, the son of a Hackney lorry driver, Marc Feld grew up as a mod on the London scene. As a broke young poseur, trying to hustle into showbiz, he got hired one day to paint his manager’s office with another kid. Marc introduced himself as “King Mod,” and declared, “Your shoes are crap.” The other kid was David Bowie. These two rivals would torment each other for years to come. In February 1969, after Bolan blew up on the U.K. charts, he invited Bowie on tour — as a mime. “Marc was quite cruel about David’s as-yet-unproven musical career,” producer Tony Visconti recalled later. “I think it was with great sadistic delight that Marc hired David to open for Tyrannosaurus Rex, not as a musical act, but as a mime.” (What could make it even sweeter for Bolan? Bowie got booed.)

Bolan released his debut single “The Wizard” in 1965, a tribute to his magic powers that impressed nobody. But this kid sure could talk the talk. He was happy to tell the London papers what a burden it was being a god. “Personally, the prospect of being immortal doesn’t excite me, but the prospect of being a materialistic idol for four years does appeal,” he told the Evening Standard’s Maureen Cleave. “I want to savor life. I want to have grey hair like Cary Grant.” He’d just turned 18.

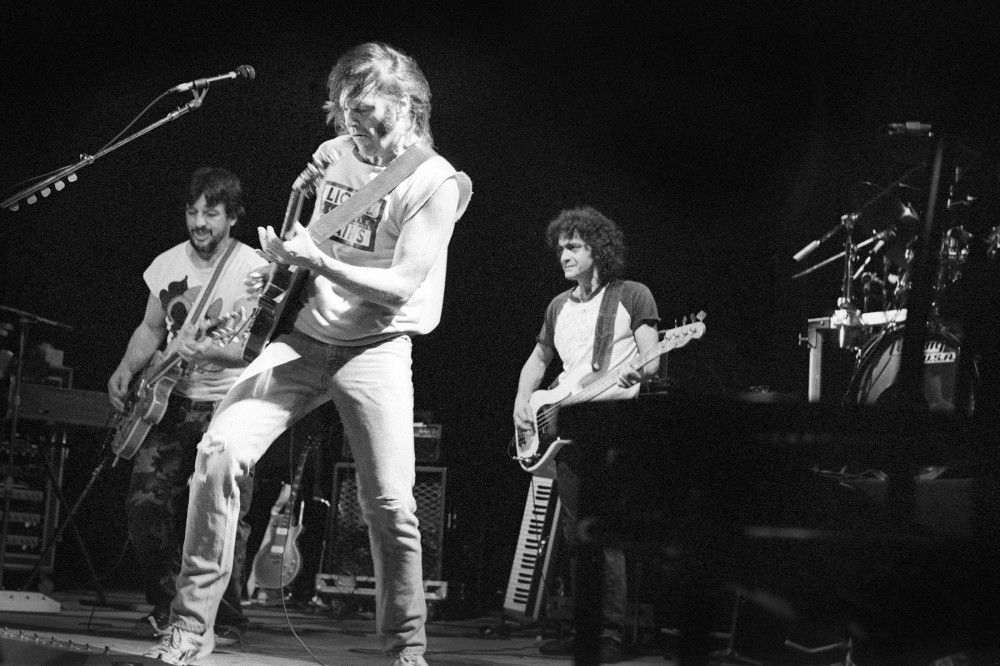

After a quick splash with his mod band John’s Children, Bolan formed the hippie folkie duo Tyrannosaurus Rex, warbling Tolken-inspired tales with acoustic guitar and Steve Took on bongos. Their 1968 debut: My People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair … But Now They’re Content To Wear Stars on Their Brows. The U.K. press dubbed him “the Bopping Elf.” Mickey Finn replaced Took for the superb A Beard of Stars. But the turning point came in 1970 when Bolan went electric for the smash “Ride a White Swan,” plugging in his Les Paul to celebrate wizards, druids and black cats. Producer Tony Visconti cranked up the reverb and added strings. Bolan followed with a string of hits — “Hot Love,” “Solid Gold Easy Action,” “Children of the Revolution,” “Bang a Gong (Get It On),” “20th Century Boy.”

Visconti and Bolan made an unbeatable artist/producer combo, especially since Visconti was also producing classics for Bowie — it fired up Bolan’s competitive edge. He never missed a chance to bitch out his glam nemesis. “I don’t consider David to be even remotely near big enough to give me any competition,” Bolan told Cameron Crowe for Creem in 1973. “He just doesn’t have that sort of quality. I do. I always have. Rod Stewart has it in his own mad way. Elton John has it. Mick Jagger has it. Michael Jackson has it. David Bowie doesn’t, I’m sorry to say.”

Electric Warrior is rightly T. Rex’s most famous album: It has the space buzz of “Planet Queen,” the vampire sex of “Jeepster,” the Kubrick doo-wop of “Monolith,” where Bolan fuses 2001 with “Duke of Earl.” The Slider came a year later, with the very underrated “Mystic Lady,” an ahead-of-its-time ballad for sisters of the moon, and “Baby Boomerang,” one of the first classics written about Patti Smith. (Bolan’s ability to crank out songs about women without the slightest trace of misogyny or machismo — well, let’s just say it sets him apart from a lot of other Seventies rockers.)

Bolan never seemed the least bit surprised by his phenomenal U.K. popularity. “There are magic mists within certain chords,” he explained. “You play a C major chord and I hear 25 melodies and symphonies up here. I’ve just got to pull one out. There’s no strain, it just gushes out.” He preened in Born to Boogie, a rock doc directed by Ringo Starr, and published his poetry book Warlock of Love.

Sadly, when it ended, it ended fast. After being a near-teetotaler most of his life, Bolan slipped into a fog of booze and cocaine after The Slider. He was already out of gas when he made Tanx in 1973, and kept bombing with Dandy in the Underworld, Futuristic Dragon, and his tragic response to Ziggy Stardust, Zinc Alloy and the Hidden Riders of Tomorrow. But in the final year of his life, he was getting it together, raising his son Rolan Bolan with his American girlfriend, Sixties R&B singer Gloria Jones. He hosted a British kiddie TV show, Marc, and for the final episode, had a touching reconciliation with Bowie. They jammed for a minute until Bolan tumbled off the stage.

Just a couple of weeks later, Bolan was killed in a car wreck. Bowie, Visconti, and Rod Stewart attended his funeral. “I’m terribly broken by it,” Bowie said. “The only tribute I can give Marc is that he was the greatest little giant in the world.” But as far as Bolan’s fans are concerned, he just danced himself into the tomb. And all these years later, that’s why the spirit of T. Rex lives on, from the ballrooms of Mars to the Hall of Fame.