The Joy of Lizzo

knows that security guard was checking her out. It’s a crisp November evening in downtown Los Angeles, and she just breezed through a Sam Ash music store to see if they had a flute-studies book by Danish composer-flutist Karl Joachim Andersen; she wants to get back to practicing the instrument she started playing in fifth grade. The door has barely closed behind her when Lizzo makes note of the guard’s not-so-subtle glance.

“He wanted to make sure he saw that thang twice!” she says, strutting down Sunset Boulevard in faux-snakeskin boots and a short, pinkish coral dress, and running her rhinestone-studded talons through her slick, wavy black hair.

How could he not do a double take when he saw Lizzo? After a decade of hustling, 2019 was her year. Five days earlier, she was running to catch a flight in Copenhagen, having just wrapped the European leg of a tour. After making it on board, she FaceTimed her manager, who was holding his phone up to a TV blasting the Grammy nominations broadcast. She found out she had earned the most nominations of any artist: eight total, including one in each of the Big Four categories. She was elated. “Then I had to sit on a plane for 10 hours,” she says.

It’s been that kind of year — surreal, gratifying, kind of exhausting. Last night, Lizzo played the American Music Awards, donning a fluffy purple gown and belting the slow, aching ballad “Jerome” to a sea of swaying phone lights. “I was worried the whole time that I would forget the words,” Lizzo says. Singing “Jerome” is one of the few points in her live show when she’s not twerking, fluting, or running end-to-end onstage. Her thoughts tend to drift. “I be sitting on the stool and my mind’ll be like, ‘So, what you gon’ eat after this?’ ” In possibly Toronto — the cities have blurred together — she had an anxiety attack midsong, but just kept singing. “I just start processing and thinking about other shit, and my mouth is just moving and the words are coming out.”

She has become, at 31, a new kind of superstar: a plus-size black singer and rapper dominating the largely white and skinny pop space, all while being relentlessly uplifting and openly sexual on her own terms. Her story is just as remarkable and radical as her stardom: years of self-doubt and struggle, followed by an unorthodox but swift ascent jump-started by “Truth Hurts,” a two-year-old song that wasn’t even on her new album.

Last April, she released Cuz I Love You, her major-label debut. She started writing the album a year earlier, around the time her first real romance was ending; the mysterious Gemini she’d been seeing would inspire practically every song. Faced with an increasingly demanding schedule and feeling disconnected from friends and loved ones, she had an emotional breakdown while on tour in the spring of 2018, a move that led her to start therapy. “That was really scary,” she told me just prior to the album’s release. “But being vulnerable with someone I didn’t know, then learning how to be vulnerable with people that I do know, gave me the courage to be vulnerable as a vocalist.”

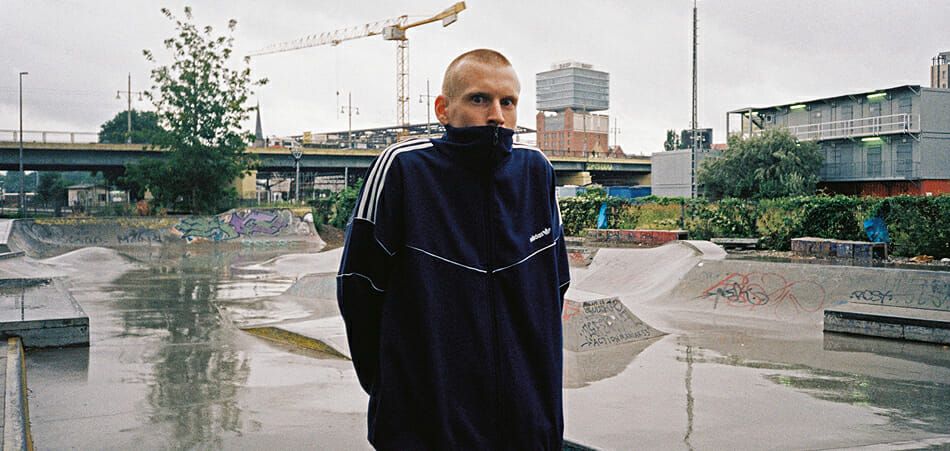

Lizzo photographed in Los Angeles on November 26th, 2019, by .

Body suit by Garo Sparo. Head scarf by Schiaparelli. Bracelet by Lorraine Schwartz. Rings by Lynn Ban. Shoes by Fashion Nova.

Cuz I Love You has its moments of heartbreak and self-reflection, but ultimately, it’s a celebration: Lizzo wants you — yes, you! — to love yourself the way Lizzo has learned to love Lizzo. In recent years, pop turned moody, in part to reflect the consistently grim state of the world. Cuz I Love You sliced right through all that. She made the type of songs she wanted to hear at the end of a rough day, songs that want you to feel beautiful, successful, booked and busy, because Lizzo feels all those things.

Now, all eyes are on Lizzo, including some of her heroes’. Rihanna gave Lizzo’s flute solo during a BET Awards performance a standing ovation. Beyoncé bopped along side-stage during her Made in America Festival set. In December, Lizzo made her Saturday Night Live debut, as musical guest for the episode hosted by Eddie Murphy. During his monologue, he noted his kids are huge Lizzo fans.

Along with greater opportunity, however, has come greater scrutiny. Lizzo came under fire for a testy Twitter response to a middling Pitchfork review she received; she said, “People who review albums and don’t make music themselves should be unemployed.” Months later, more ill-advised tweets led to a libel lawsuit after she falsely accused a Postmates driver of stealing her order, sharing the driver’s name and likeness with her million-plus followers.

As a dark-skinned black woman doing the uncool (but very lucrative) thing of making uplifting pop music, insults tend to be harsh and personal. She’s been called corny and an “industry plant.” In a since-retracted headline, cheeky gossip site Bossip called her a “Kidz Bop Kween,” suggesting that her music is watered-down imitations of more authentic pop. The most consistent, painful insult, though, is that she makes music for white people, that she’s merely shuckin’ and jivin’ for an audience of yas kween-era white feminists. “Yeah, there’s hella white people at my shows,” she asserts, with a smirk. “What am I gonna do, turn them away? My music is for everybody.”

Ironically, seeing majority black women in her audiences while playing shows with SZA in 2015 was a major inspiration for the songs that are finally climbing up the charts. “Coconut Oil,” in particular, was meant to be a self-care anthem for black women. “As a black woman, I make music for people, from an experience that is from a black woman,” the singer says. “I’m making music that hopefully makes other people feel good and helps me discover self-love. That message I want to go directly to black women, big black women, black trans women. Period.”

She’s learning to check herself, living in the “real world” offline and not responding to the haters. “That was the end of that era for me,” she says of her Twitter snafus. “I was fuckin’ wrong. I’m big enough to admit that shit.” In early January, she decided to quit the site, at least for a while, because of both the trolls and more general “negativity” toward everybody.

To some degree, she understands the critiques. “Look, I’m new,” she offers. “You put two plates of food in front of people, and] one is some fried chicken. If you like fried chicken that’s great. And the other is, like, fried ostrich pussy. You not gonna want to fuck with that.”

She may be “fried ostrich pussy” for some listeners, but she’s not going anywhere — not after all it took to get here. “We eventually get used to everything,” she says. “So people just gon’ have to get used to my ass.”

Photograph by David LaChapelle for Rolling Stone.

Gold headdress by Yana Markova. Jewelry by Lynn Ban. Crystal SnakeSkin Jewelry by J. Maskrey.

On December 31st, 2018, Lizzo decided she didn’t need to make any resolutions for 2019: She had accomplished everything she wanted. She was recording songs she loved, and her shows were sold out. “I grossed a million dollars on my tour. I was able to put my friends on my payroll,” she says. “I was Gucci.” She was also about to experience one of pop’s craziest success stories.

Lizzo always figured she would write a massive pop hit. Best friend and longtime collaborator Sophia Eris remembers how fast Lizzo would write songs for their pop-rap trio the Chalice, which they formed in 2011 in Minneapolis. After Lizzo was signed to Atlantic in 2015, Eris saw her friend fully comprehend her own creative power. “She said, ‘I’m pretty sure I know how to scientifically make a hit,’ ” Eris says. “She has the brain of a chemist. She knows the equation. Lizzo could write a hit in her sleep.”

Lizzo’s pop ear made both her and her label impatient for a hit. Her 2016 EP, Coconut Oil, was buzzy but fell flat. “There was a sense of frustration at times because we knew how amazing she was, and we saw the potential,” says Atlantic A&R executive Brandon Davis, who signed Lizzo to pop producer Rick Reed’s imprint, Nice Life, in December 2015.

In 2017, she dropped “Truth Hurts.” Half-rapped, half-sung, it was both a breakup kiss-off and an empowerment anthem, balancing cheeky humor, a touch of pain, and a whole lot of confidence. “It was the first song that was like, ‘Oh, this is a cool song,’ ” she continues. “Most of my rap songs were so lyrical spherical, you know? On ‘Truth Hurts’] I’m doing that rap-singing thing and the beat was lit. I was proud of it. I could play it for my friends back home in Houston.” Not long after Lizzo wrote “Truth Hurts,” she visited a psychic, who began quoting lines from the song. “I was like, ‘What the hell?’ And she was like, ‘You should just get married to yourself.’ ” Lizzo does just that in the song’s video.

“Truth Hurts” was ingenious, catchy as hell, and a total flop. When it seemed to disappear, Lizzo wondered if she should too. She considered quitting music altogether. Her team talked her out of it. “Truth Hurts” would remain a centerpiece of her live show, but she moved on, focusing her attention on Cuz I Love You.

On October 20th, 2018, Lizzo posted a video from a show in Iowa City, Iowa, on Instagram. It was of her playing flute while covering Kendrick Lamar’s “Big Shot.” Lizzo and her backup-dancing Big Grrrls hit the shoot dance in the middle of the song before she resumes her flute-playing. “I think that was another reason why I was so satisfied,” she continues. “Because I was known as a flute player now. Secret’s out: I am a band nerd.”

In less than 30 seconds, Lizzo had hit something in the often-confusing viral-content zeitgeist, and her #FluteAndShootChallenge became a phenomenon. She served up more viral content — specifically, videos of her coolly saying “Hi bitch” and “Bye bitch” on golf carts, escalators, and other in-motion settings — and became her own meme-generating machine. She was growing an audience.

Photograph by David LaChapelle for Rolling Stone.

Dress by Christian Siriano. Earrings by Lorraine Schwartz. Rings by Archive Lynn Ban. Flower in hair by Bijou Van Ness.

Lizzo released Cuz I Love You in April 2019. Critics liked it, and it racked up good, if not outstanding, streaming numbers. Then something strange happened. Someone Great, a breakup dramedy starring Gina Rodriguez and Lakeith Stanfield, dropped on Netflix the same day as Cuz I Love You. The film happened to feature “Truth Hurts,” soundtracking a memorable scene of Rodriguez’s brokenhearted character day-drinking, dancing and shouting along to the track in her underwear. “It was always my intention for this moment to be able to live outside the film as a stand-alone clip,” says the film’s director and writer, Jennifer Kaytin Robinson, who first heard Lizzo in 2016. She was inspired by the “Tiny Dancer” scene in Almost Famous, and “Truth Hurts” was her first choice.

Someone Great changed everything. “Waking up the next morning, we tangibly felt things were different,” Davis recalls. “Truth Hurts” began climbing up Shazam’s and iTunes’ charts as it rocketed around on social media. Younger listeners were simultaneously discovering the song through “DNA test” memes on TikTok.

Suddenly, Lizzo’s two-year-old song, a song not even featured on her new album, was a smash, topping the Rolling Stone 100 songs chart. Then, after performing a medley of “Truth Hurts” and 2016’s “Good as Hell” at the MTV Video Music Awards, the latter song became Lizzo’s second sleeper hit.

Meanwhile, songwriters Justin and Jeremiah Raisen accused her of lifting the opening line of “Truth Hurts” (“I just took a DNA test, turns out I’m 100% that bitch”) from a demo they worked on together. The line had been inspired by an Instagram meme Lizzo had seen, originating from a tweet by singer Mina Lioness. Lizzo responded with a lawsuit alleging harassment and offering an official writing credit to Lioness. “The creator of the tweet is the person I am sharing my success with. Not these men,” she wrote in a statement.

Lizzo is diplomatic about her weird career trajectory. No one can exactly plan for multiple old singles to suddenly pop after releasing an album full of new material. “When we were making it we knew it was ahead of its time,” she says. “Now we have the proof that these songs are timeless. They will connect when they need to connect.”

When I brought a friend to see Lizzo perform at Brooklyn Steel this past May, she cried. We’re both roughly the same size as the pop star, wide and curvy, with leg dimples and arm flab and round bellies.

She cried because she has never been able to say that about a person she saw performing onstage before, let alone a plus-size performer belting, rapping, and dancing instead of standing still with her body covered. In a world where we were told to believe that slightly curvier-than-average features on the slim figures of Jennifer Lopez, Beyoncé, or Kim Kardashian are somehow extraordinary, it felt radical.

“It’s completely life-changing,” plus-size fashion designer and influencer Gabi Gregg says, giving credit to Beth Ditto and Missy Elliott for helping pave that way. “When you get to see her, it’s so impactful and almost brings tears to your eyes because you think], ‘I knew that was missing my whole life, but I had no idea how much it would mean to actually see it.’ ”

Gregg first became a fan of Lizzo when the pop star dropped the video for 2015’s “My Skin,” a raw ballad about learning to love yourself, that featured a more natural look than her usual glam. “I wrote ‘My Skin’ when I was 26, so at that point I had already gotten to a place where I’m confronting myself and I’m happy with it,” Lizzo explains.

Her late teens and early twenties were marred by low self-esteem worsened by a toxic lover’s desire for a thin girlfriend. “My Skin” reflects years of work she had done to unlearn the ways society had told her to hate herself. “I’ve come to terms with body dysmorphia and evolved,” she says. “The body-positive movement is doing the same thing. We’re growing together, and it’s growing pains, but I’m just glad that I’m attached to something so organic and alive.”

Photograph by David LaChapelle for Rolling Stone.

Fans and headpieces by Bijou Van Ness; Jewelry by Dena Kemp. Shoes by Pleaser.

Soon after “My Skin,” Lizzo’s team reached out to Gregg for advice. The singer was beginning to change up her game from the flannel and Duck boots she swore by in Minnesota. Gregg helped Lizzo’s stylist find brands that catered to plus-size bodies, and later appeared in the video for “Scuse Me.” “I was thinking about how meaningful this moment in time is for plus-size women,” Gregg reflects. “Things are really changing.”

There’s change, but the progress isn’t always so clear. In December, Lizzo’s body became fodder for more debates when she dared to twerk at a Lakers game in a dress that exposed her thong-wearing ass. Peeved Lakers fans accused her of violating the “family friendly” event and compared her body and outfit to that of a professional wrestler; Twitter users fixated on faces of players and attendees that showed mild, and quite possibly unrelated, disgust.

Lizzo seems a touch exhausted talking about her body, which is fair. She wants to be celebrated for her music — and not seen as “brave” for doing so. “I’m so much more than that. Because I actually present that, I have a whole career,” she says. “It’s not a trend.”

Melissa Jefferson was never sure she could be a solo star, so for most of her life she joined groups. The first was her family church’s choir in Detroit. She wasn’t known as “the singer,” and that was OK: She was the “smart one,” with dreams of being an astronaut. In her spare time, she wrote fantasy stories about strong women she one day hoped to emulate, and began a lifelong love for anime like Sailor Moon.

When she was nine years old, her parents moved Melissa and her two older siblings to Houston. Shari and Michael Jefferson owned a real estate business, and Texas offered lucrative opportunities. “I was like, ‘Wait, what the hell?’ ” Lizzo recalls. “I didn’t even get to really process leaving, and I was like, ‘Now we about to be around all these horses and cowboys.’ ”

Down South, she found something she was best at: the flute. Her instrument was chosen for her in a mandatory band class, and it felt like fate. “I was just so good at flute,” she explains. “I thought], ‘This is it for me. I’m going to college for this shit.’ I knew back then.” Outside of band, Lizzo was made fun of in class for know-it-all habits: “I would always raise my hand, and they be like, ‘Damn, how many questions you gonna answer, nerd?’ ”

She was “private” but still outgoing enough to audition friends for a Destiny’s Child-inspired girl group. The first song she wrote for the group was called “Broken Households” — about children, unlike herself, who grew up in broken homes. Lizzo still didn’t feel like she could sing, so she directed the other members to belt out the sad tune. Eventually, she formed Cornrow Clique, her first proper band. The lineup featured three friends who went by Nino, Lexo, and Zeo. Melissa became “Lisso.”

By high school, she had transitioned from nerd to class clown. It came from the same place as her know-it-all tendencies: “a desire to be listened to,” she says. She enrolled at the University of Houston to study music, but college was a struggle: “Math. Walking on campus, that big-ass school. Money.” The pressure mounted, and she dropped out when she was 20. Leaving college meant abandoning the dreams of becoming a professional flutist.

She continued rapping with a friend from the since-disbanded Cornrow Clique, but self-doubt began to creep in: The friend she continued to perform with seemed better-suited for success. “I always thought she was the more special one ’cause she was thinner than me, and the boys liked her and stuff. ‘Let me just write the raps and support her.’ ”

The duo ended, along with the friendship, and Lizzo’s next couple of years in Houston were peppered with guilt, fear, and embarrassment. She auditioned for a prog-rock band called Ellypseas, lying about her level of singing experience. She got the gig, but at the expense of severe nerves that she treated each night with shots of whiskey before going onstage. Fans loved her energetic, sometimes erratic stage presence, but she was still unhappy, hiding her new band from friends, who she feared wouldn’t like the music.

Lizzo quit Ellypseas in 2010, a year after her dad died. She feared that giving up college and her dreams had let him down. “My dad was an advocate for my flute, and he wanted me to go back to college really badly,” she says. “He was going around trying to get money from my cousins to put me back in school. And I’m like, ‘I’m not going back to school.’ I didn’t tell him that though.”

Lizzo struggled to make ends meet, living out of her Subaru for a period. In 2011, a friend and collaborator was planning a move to Minneapolis and invited Lizzo to come along. Ready for a change of scenery, she took a chance.

Photograph by David LaChapelle for Rolling Stone.

Robe by Catherine D’lish. Headpiece and hand jewelry by House of Emmanuele. Rings by Lynn Ban. Sativa pre-roll by Lowell Herb Company.

In Minneapolis, Lizzo was rapping again, and at the time was one of the few black women in the city doing so. She and Eris soon formed the Chalice, another Destiny’s Child-inspired girl group. The group became local celebrities. Then they got the ultimate co-sign for any Minneapolis musician: Prince was a fan. In 2014, Lizzo and Eris appeared on Plectrumelectrum, an album by Prince and his backing band 3rdeyegirl, singing on “Boytrouble.” Prince invited them back to perform at Paisley Park; later, His Royal Badness even played a solo piano show for them and a few others. Before he died, he offered to produce an album for Lizzo.

For Lizzo, this kind of respect was life-changing. “I used to be so upset that I never had co-signs,” she told Rolling Stone in 2018. “I was like, ‘I’m too weird for the rappers and too black for the indies.’ I was just sitting in this league of my own. To be embraced by Prince and co-signed, I am eternally grateful for that.”

A week after we meet in L.A., the high priestess of self-empowerment is playing a Jingle Ball concert at Dallas’ Dickies Arena. Backstage, she fields crying fans at a meet-and-greet while wearing drawstring Gucci pants, a Gucci top, and cozy-looking camel boots that she asks the photographers to avoid shooting. A bag of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos seems to appear out of thin air as she jumps from radio interview to radio interview, fielding questions about everything from her tastefully nude photos (“Everybody’s naked a lot!”) to her dating life (Lizzo never DMs first).

Lizzo is selectively revealing, as all the best self-help gurus are. She reveals key parts of her journey while holding back the best bits of herself for the people who have been with her for a decade-plus. She was, after all, private even in her youth.

But one reason her brand has been so successful is that her positivity isn’t idyllic or saintly. She’ll get angry or depressed, cruel or weepy. She’s a bundle of feelings, some of which have come out in interactions with trolls and Instagram Lives, where she offers unfiltered commentary on happenings in her life and feelings.

While she found the right way to explore love in her music, she can stumble while talking about it in person, still trying to maintain her privacy. The first time she thought she was in love coincided with one of the lowest points in her life. She was 19 and “delusional,” trying to be someone she wasn’t. “Skinny guys like me,” she says with a light chuckle. “But I remember he was like, ‘I’m a little guy. I need a little girl.’ ” Because it was 2007, she tried to emulate Zooey Deschanel (“I can’t just wake up and be a white girl”). The demise of the relationship made her ask a question she would try to answer in her music for years to come: “How can you be in love with someone when you’re not even you?”

Two years ago, a more confident Lizzo fell in love for real — this was the unnamed Gemini of Cuz I Love You fame. She chalks up the demise of that relationship to bad timing and her need for freedom. “As fucked up as it sounds, I needed that heartbreak experience,” she says. “I’m not sad, because I use the pain so constructively. It’s inevitable. The pain is human experience.”

For a long time, the future she had perceived for herself was a lonely one — “no children, two friends” — with her head buried in her work. “But it’s different now,” she says with a sigh, dropping the advice-guru voice she delivers her self-help sermons with on- and offstage. “Like my relationship with my family, I’m working on that. I open myself up to friendships. I open myself up to the idea of children, which is big for me, ’cause my albums are my babies.”

While driving around Los Angeles a week before, she had put her work-in-progress relationship with her brother to the test, informing him FaceTime that he couldn’t spend the night at her place before they drove to Joshua Tree for Thanksgiving because she was expecting company. “I feel so bad,” she groaned after hanging up. “But I’m tryin’ to get my pussy licked!” Lately, she’s been writing songs while on the road, mostly inspired by the “cute little things” more recent lovers have said to her. “That’s the good shit right there.”

Lizzo finds another potential suitor in Dallas when she runs into Charlie Puth backstage. She shoots her shot in front of his parents and sister. “We’re about to make out and it’s gonna get weird!” she shrieks as they prepare to take a photo together. She calls his dad her father-in-law before the two artists pantomime walking down the aisle to Puth’s hummed version of “Bridal Chorus.”

It’s all a joke, Lizzo coming alive for the cameras one last time before she clocks out for the day. Still, the ruse goes on long enough that you kind of wish they’d run off to city hall someday.

“Call me,” Lizzo says as she winks at Puth, hands clutching the robe of her sexy-Santa costume. She’s given him the greatest gift of all: the hope he could one day be with Lizzo. She’s done for the night.