'Teenage Dirtbag' 2.0

“The choruses of ‘Teenage Dirtbag’ are doubled, Ozzy Osbourne-style,” says Brendan Brown, singer, songwriter, and sole remaining original member of Wheatus. “Those high notes have to be good or else they don’t work together, so sometimes it takes a little while.”

For the past hour, Brown, 48, has been re-recording the immortal refrain to his 2000 hit “Teenage Dirtbag” in his cramped home studio in the Bronx, New York. “‘Cause I’m just a teenage dirtbag, baby,” he sings during eight distinct vocal takes. “Yeah, I’m just a teenage dirtbag, baby/Listen to Iron Maiden, baby, with me, ooooh.”

“The part I didn’t like was the ‘me,’ and I think it was the ‘me’ on the bottom,” he says after his seventh try, talking to current Wheatus bandmates Joey Slater and Gabrielle Sterbenz, who is also his girlfriend.

“Yeah, but it’s a good ‘Maiden,’” says Slater.

“It is a good ‘Maiden,’” says Brown.

Brown tries again.

“The first ‘dirtbag’ is really good,” he says after a different attempt, still unsatisfied.

“To me, it sounded like it did last night,” says Sterbenz. “I think the high was OK. It was the low one that was a little off.”

“This is mostly what we do,” Slater says. “We listen to two things that sound basically identical, and decide which one we like best.”

Slater, it soon becomes apparent, is being literal: For the better part of the past two years, the three have been holed up in a basement studio meticulously re-recording every single instrument and vocal part to Wheatus, the band’s 2000 debut that spawned their sole hit, went platinum in the U.K., and charted in a half-dozen countries.

In an era when hollowed-out streaming revenue has practically forced aging musicians to monetize classic-album anniversaries, Brown is going further than almost anyone. Later this year, the band will release a 20th-anniversary album-length re-recording of Wheatus, which they plan to promote on a fall tour with fellow turn-of-the-21st-century rockers Alien Ant Farm. And around that time, there are plans to finally release a decade-in-the-making Wheatus documentary called You Might Die.

Brown’s re-recording project has cost him countless thousands of dollars, and hundreds of hours spent obsessing over bass lines and synth sounds fans almost certainly never noticed in the first place. His quest has sent him scouring the internet for gear that most closely resembles what the band originally used to record the album. He describes this process as a “fucking pain in the ass.”

“It’s not exactly fun,” he adds. “It’s, like, forensic.”

The end result is an impressive technical feat that no passive listener would ever distinguish from the original.

So why, then, is Brendan Brown doing any of this? The short answer: He no longer possesses the master recordings to Wheatus. The album was recorded on a long-defunct transitional format called ADAT. Years ago, Brown gave his last personal copy of the masters to his former label, Sony, and he’s never seen them since.

For a musician whose lifelong income is very much dependent on a single song, this is a problem. Brown is very aware that “Teenage Dirtbag” is his career calling card: Online, to this day, he’ll respond to fans’ queries about the song by granting them “dirtbag for life status.” After rescheduling some of his 20th-anniversary touring plans due to the coronavirus, Brown announced the “Quaranteenage Dirtbag Challenge,” in which fans will submit their own versions of the song, to be then edited into an eventual video.

Brown is far from alone in his obsession with the song. For a single that never even entered the pop charts in the U.S., “Teenage Dirtbag” has become a surprisingly enduring cult standard. On its surface, its a time capsule of Eighties heavy-metal lonerism and oversized bucket hats, which Brown donned for the song’s goofy music video that incorporated scenes from the forgotten Jason Biggs teen comedy Loser. But its dark backstory — involving years of Brown getting beaten up by older teenagers as well as a horrific murder that took place in his Long Island hometown when he was young — gives it an unexpected emotional gravity that’s transcended its era. These days, it’s embraced by both aging millennials and an entirely new audience of devotees from all across the musical spectrum.

One Direction, SZA, 5 Seconds of Summer, Phoebe Bridgers, Mary Lambert, All Time Low, Rex Orange County, and Amy Shark have all covered the song in recent years. “We’re just teenage lads,” One Direction’s Liam Payne explained in 2013. “We’re not saying we’re dirtbags, but we’re grimy characters.”

“The whole point is that you can feel these emotions, and there’s a validity to them in your adult life,” says singer-songwriter Ruston Kelly, who included not one but two covers of “Teenage Dirtbag” on his 2019 album Dirt Emo Vol. 1. “The song hits as much as a 31-year-old adult as it did when I was 15. I had thought that ‘Teenage Dirtbag’] was kind of a deep cut or throwback, but at my shows, the grunge kids, the art kids, they all fucking love this song.”

The first time Brendan Brown ever saw the word “dirtbag” in writing, it was in a 1984 Rolling Stone story about the gruesome murder of a 17-year-old in his hometown of Northport, Long Island. That summer, a teenager stabbed his friend to death, leaving his body in the woods, where he showed the corpse to friends for a full two weeks before the crime was even reported to the police.

Brown was 11 when he read author David Breskin’s description of several teenagers, taken from the local lingo Breskin had picked up after spending the summer in Northport, as “veteran dirt-bag street kids].”

“He used the word correctly,” Brown says of the Rolling Stone story. “But I don’t think it should’ve been hyphenated.”

The murder of Gary Lauwers traumatized the small town of Northport. Brown’s parents decided to send him 80 minutes away to an all-boys day school. After attending college in Pennsylvania, a twentysomething Brown ended up in New York, playing in a local band that ended up scoring a gig opening for Joan Jett.

Before he ever wrote a word of “Teenage Dirtbag,” Brown had the title. The riff was an amalgamation of everything he was listening to at the time: Willie Nelson, Cyndi Lauper, AC/DC, Ani DiFranco. “I tried to juxtapose all the metal that I was into sonically and tonally, and all the ‘Fire and Rain’-type acoustic tones you would hear from a Paul Simon or Indigo Girls record,” he says.

Benson in his home studio. Photo by Joey Slater

Joey Slater

The first half of the song came easily. The hardest part to write, and the section of the song that Brown seems most proud of, is the infamous third verse. Brown sings the second half in falsetto as he switches his first-person narration from himself to Noelle, the girl that the song’s lonely-boy protagonist has spent the past two and a half verses daydreaming about.

Brown chose to sing about Iron Maiden because he viewed the band, famed for their 1982 classic “The Number of the Beast,” as the archetypal target of Tipper Gore’s heavy-metal-as-satanism crusade during the Eighties — a mindset that was ever-present in Brown’s hometown after the Lauwers murder. “That was like noticing adult hypocrisy for the first time,” Brown says.

Brown also drew on his childhood for the high, feminine voice he adopts in the song’s third verse, a self-protection measure he would employ as a kid when older teenagers would bully him.

“If somebody called me a faggot, I would just taunt them in a high girl voice,” he recalls. “I would get beat up by older kids, and there’d be a lot of homophobic slurs. They didn’t know anything about you at all; it’s just what they said. I found that it’d compress the time that you’re actually having the shit kicked out of you if you antagonized them by donning a girl voice.”

When the song was first released, Brown kept its backstory to himself. “I just felt it was smart to edit myself,” he says. “It isn’t like a fun pop-song conversation.”

He formed Wheatus in 1995, shortly before writing “Teenage Dirtbag.” He recruited his brother, Peter, on drums, as well as bassist Rich Liegey and multi-instrumentalist Philip Jimenez, who returned to mix the band’s 20th-anniversary re-recording. When the band got a major label deal in 1999, Sony wanted to release the group’s demos as the album, but Brown refused, spending $50,000 of Wheatus’ advance on gear to re-record “Dirtbag,” which he’d been working on for a few years.

“I changed everything,” Brown says of the three weeks the band spent at his mother’s home in Long Island reworking “Dirtbag” in early 2000. “I tore the guitars apart, built them back together again. A lot of prototyping. The thing I wanted it to sound like was a very fuzzy, yet very punchy wall of sound — J Mascis, Bob Mould, Sugar stuff — but also AC/DC–type clarity on the punch of the drums. And then to also have the low end of hip-hop. It took four years to find out what the stupid song was supposed to sound like.”

Brown says that Sony tried its best to convince Brown to kick out Jimenez in order to shape the band in the mold of contemporary power trios like Blink-182 and Green Day, another suggestion that Brown turned down.

Brown saw “Teenage Dirtbag,” and more generally, his band, as a subtle rejection of the hyper-masculine rock music that was selling in the tens of millions in the late Nineties. “There was a little bit of a toxicity to tough-guy music emerging around that time that I very much wanted to distance us from,” he says.

Being neither a boy band nor a macho hard-rock group, Wheatus didn’t fit into the pop landscape. “In America, we were hard to place,” says Brown. “Record executives literally said to me, ‘I need you to re-sing this song more like a guy, because radio won’t have you singing like a girl.’ With pop radio, it wasn’t fitting well because it had heavy guitars and we talked about guns and dicks and shit.”

The timing of the song’s release didn’t help. The band delivered the finished version of the song to the label in April 2000, just a few weeks before the one-year anniversary of 1999’s Columbine school shooting. Sony told Brown he wouldn’t be able to sing the line about the boyfriend “who brings a gun to school,” and asked the band to change it. Brown refused, instead conceding to a radio edit that played record scratches over the word “gun.”

“We were these douchebags from Long Island; we didn’t know anything,” he continues. “We never looked the part, either. I constantly was hearing from Sony, ‘You guys are a little overweight.’ That kind of stuff.”

“Dirtbag” never became a hit in the U.S., where it failed to chart. But internationally, it was an instant blockbuster, going triple platinum in Australia.

“Even though it wasn’t stylistically of the moment, we just felt the song was undeniable,” says Blair McDonald, the former managing director of Columbia in the U.K., where the song immediately became a radio hit. “It was such an obvious instant-monster musical moment that it didn’t really take any understanding.” Thanks to a series of covers by British acts, including One Direction, the song would go on to re-enter the British pop charts six years in a row, from 2011 to 2015.

Wheatus originally recorded their debut album on ADAT, a quirky transitional multitrack system that was widely used in the Nineties but quickly became obsolete. When the album came out, Brown says he was asked to send his personal copies of the masters to his label, because they wanted to remix songs from the album.

“I told my A&R guy, ‘This is my last set of masters — are you guys putting them on backup?’” Brown says. “We never found out where they went.”

Wheatus and Sony maintained a strained relationship after the debut, and by 2005, following one more LP, the band was no longer on the label. Brown has queried Sony for years about the whereabouts of his lost masters, to no avail. “They would get annoyed when you would start tech-nerding them, like, ‘What are you bothering me for?’” he says.

Brown is convinced that Sony either never transferred the tapes — rendering them virtually unplayable — or simply lost them. Either way, Sony has never given him a straight answer. (An A&R executive at Sony did not respond to multiple questions about the status of the master recordings from Wheatus’ debut album.)

“Teenage Dirtbag” still generates a good portion of Brendan Brown’s yearly income. “I would call it a very fortunate working-class musician position to be in,” he says, “almost like we own a deli.” But for Brown, not owning, or even possessing, the master recording to Wheatus has been a decade-long source of frustration and anxiety. It’s prevented him from capitalizing on huge potential windfalls, like, for example, when he claims that the Chainsmokers came calling a few years ago asking to remix “Teenage Dirtbag,” and Brown, having no original multitrack tapes to give them, had to say no. (A representative for the Chainsmokers “politely passed” on commenting on this anecdote.)

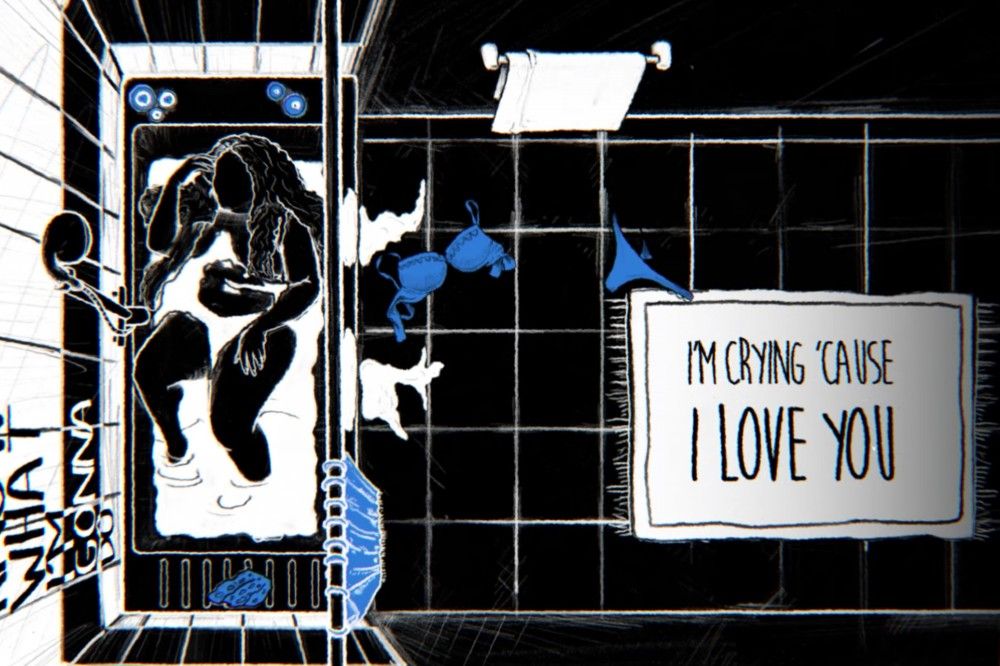

“My voice hasn’t really dropped yet, so I can still do it,” Benson says of re-recording “Dirtbag.” Photo by Matthew Milligan

Photo by Matthew Milligan

With the re-recorded version of Wheatus, Brown will, finally, possess new masters of “Dirtbag,” a crucial asset should the next Chainsmokers ever come calling. But on a deeper level, completing this project will also help Brown feel like he finally has control over the most important work of his life.

“It’s like being made whole again,” he says. “If you make something, and you’re precious about the process, and then you deliver it to the world, and then suddenly it’s inaccessible to you, forever — that’s kinda shitty. It’s troubling. Feeling whole, one song at a time, is really nice.”

“And, fortunately,” he adds, “my voice hasn’t really dropped yet, so I can still do it.”

There’s something slightly wrong with the preamp levels in the studio, and Brown floats a slightly outlandish theory: The local electric utility is servicing an ever-so-slightly different level of power to the neighborhood today, he thinks, and it’s affecting the gear.

“I think my ‘listens’ sucked,” he says after yet another attempt at re-recording the chorus to “Dirtbag.” “We were in the sweet spot last night, which is weird, which is why I think it’s the power.”

“It’s driving me fucking bananas,” he continues, still comparing his vocal take from the previous night to today’s attempts. “Because every time I hear this, I like it for one reason, but then I hear the other one and I’m like, ‘This is the mix.’”

Understandably, “Dirtbag” has tortured Brown & Co. more than any other song on the re-recorded debut. “This is definitely the hardest one to reclaim,” Brown says. “Once this falls, the rest will be on the assembly line.”

At times, the band talks about the song’s musical complexity as if it’s a Beethoven symphony. Wheatus’ modern-day drummer, Leo Freire, told me that he rehearsed the song’s drum parts with Brown for five weeks before even recording it. (David Thoener, who mixed the original “Teenage Dirtbag,” says, “I’ve read that Brendan feels the snare-drum sound dates the song. I don’t think people who love the song care at all what the snare drum sounds like.”)

Brendan Brown remains grateful for his sole blockbuster hit. Instead of growing resentful of being what many would call a one-hit wonder, Brown has embraced its longevity. When I ask him if he’s ever gotten sick of the song, he says “no,” practically before I finish the question. “I have never gotten sick of it, of playing it. Very lucky that way.”

Still, he finds it strange that a song written about his own teenage despair has become part of a collective generational consciousness.

“What the song has done on its own, that means that whatever drove people to the song is way more important than some satan murder in my hometown,” he says. “I never did Halloween stuff when I was a kid. I just watched out the window as the rest of the kids toilet-papered and egged our house. You develop ideas in solitude that can be destructive, incredibly destructive, and can also lead you to be skeptical of herd mentality and groupthink. So, I guess what I’m trying to say is that some part of this song represents incredibly bleak solitude for me, and conversely, a lot of people know about it. It’s a very strange, stark juxtaposition.”

As beloved as “Teenage Dirtbag” is, it’s hard to imagine that any listener has spent too much time obsessing over the glitchy, three-note, synth-like sound that briefly shows up in the first chorus, right after the “she rings my bell” line. Still, last September, Brown attempted to crowdsource its origin, offering an engineering credit for anyone who could track it down. He was unsuccessful, and ended up having to attempt to reproduce the sound on his own.

“It turned out to be so much more complicated than we could have imagined,” Brown says, before explaining the process at length.

“We spent nine days transposing and moving harmonies around, moving the sound] to different harmonies so that it sounded like the original, because we don’t know what the original sound] was. It was just a phone thing sampled from somewhere,” he says. “It took us nine days until two o’clock in the morning. We were freaking out, like, ‘What the fuck? How do we do it?’ Anyway, we got there, but the process was like, ‘You gotta be fucking kidding me.’ We had to do all this research on DTMF, the Bell telephone system, to figure out what the notes corresponded to. … The sound happens again in the third verse, and they’re actually different harmonies. We got the first verse right, and the third verse wrong, so we had to start the transposing process all over again. That was another three days.”

Brown stops and looks up, almost as if he’s come out of a trance. He stops himself, cracks a smile and says, “Anyways, do you want to hear the new version of the song?”