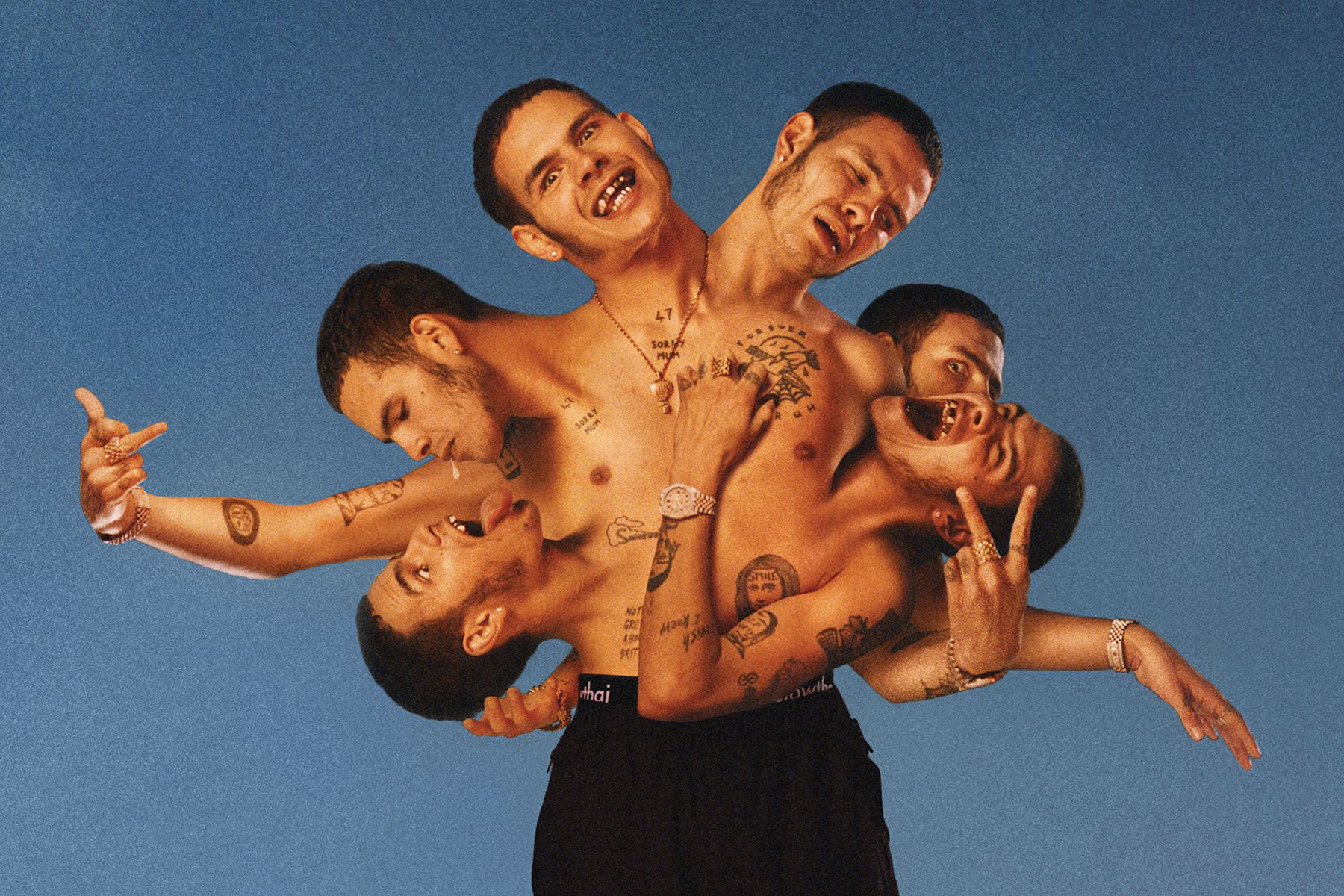

Shoetown’s Hero: Slowthai on How Community and Contradictions Shaped ‘Tyron’

Northampton, situated about 90 minutes north of London in Britain’s East Midlands, is best known for making shoes. Its residents have been churning out footwear since the 17th century, when they provided the boots worn by Parliamentarian soldiers in the English Civil War, and the town remains home to some of the best shoemakers in the world. “People travel to get these shoes, and that’s always been the thing we’re known for,” says Slowthai, 26. “It makes people think it’s a bubble here, like this is as far as it goes. They’re up here, we’re down here. It’s a ‘Shoetown’ mentality.”

The gap-toothed, sharp-tongued MC, born Tyron Frampton, stepped out of Northampton and left a print on his country’s London-centric hip-hop and grime scenes around 2017. Songs like “T N Biscuits” and “Ladies” were a bit grime, a bit U.K. drill, a bit punk; the bars balanced ferocity and vulnerability and conveyed a seething clarity about the anxieties, inequities, indignities, and dead-ends facing those growing up in post-recession British austerity. His 2019 debut, Nothing Great About Britain, made Slowthai a critical darling and a budding star.

Slowthai describes Tyron, his second album, out February 12th, as a much more personal project. Though work began at the beginning of 2020, he made much of the LP during lockdown, while he was living back at home in Northampton with his mother and fiancé. For this interview, he Zoomed in from his charmingly cluttered basement studio, where a ladder of keyboards and synths rose up against a wall, and cups of old tea and other tchotchkes lay strewn about his desk. Tyron is split into two halves — opening with fire and rage before cooling into something more meditative and poignant — a creative choice to echo its thematic concepts of contradiction and duality.

“I felt like, coming off the back of all the bullshit going on, that people only see one side of you through their phone or computer screen, and most of the time that’s not who we are,” he says. “That’s the image we want people to see, or we believe is us. But then there’s the side of us where we’re just home, chilling with people. The people who are closest to you know you better than anyone, so it’s just allowing people to see into that. Pull back the curtain, if you will, and lock in.”

The Tyron most people saw over the last two years was the one who could swallow you with a grin while cursing out the Queen or closing a performance at the 2019 Mercury Prize ceremony by holding up a fake decapitated head of Prime Minister Boris Johnson. He did a U.K. tour where tickets cost a fiver. At a Brooklyn club in 2019, I watched him take time in between songs, not to catch his breath, but to shape the crowd into large circles, triangles, trapezoids, and squares, just to have them collapse into pits at the next beat drop. Opening for Brockhampton at the theater at Madison Square Garden a few months later, he commandeered the bigger stage with equal ease; a solid chunk of the American crowd even knew all the words. Since then he’s done a song with Gorillaz, recorded a riotous Tonight Show performance with Mura Masa, and scored a Grammy nomination for his track with Disclosure and Aminé, “My High.”

Then there was the Tyron people saw last February at the NME Awards. It was about a week after that Tonight Show appearance, and, back in England, Slowthai was on hand to receive the “Hero of the Year” award. Early in the show, he did a bit with the host, Canadian comedian Katherine Ryan. He’d had a bit to drink. He took a bit of cheeky banter they’d rehearsed earlier somewhere too lascivious. The backlash was fast online, but also in the crowd: When Slowthai went up to accept his award later, there were boos, someone appeared to call him a misogynist, things were thrown. He jumped off stage, there was an altercation, and Slowthai left the ceremony. The following day, he apologized to Ryan on Twitter and sent her the award. Ryan, for her part, said Slowthai hadn’t made her uncomfortable and compared the moment to a comic dealing with a drunk heckler.

Tyron isn’t solely a reaction to that night, though Slowthai acknowledges that the whiplash of going from hero to villain put into stark relief the themes he’d already been mulling. In Northampton, he settled into lockdown and the self he knew himself to be among his closest friends and family. He gave up drinking — a vice he’s admitted to leaning on too hard while touring — and focused on making music with a group of collaborators who’ve been with him for years: Kwes Darko, SAMO, Krash, and JD Reid. The record also features grime great Skepta (who featured on Nothing Great About Britain), plus new friends and peers like James Blake, A$AP Rocky, Mount Kimbie, Kenny Beats, Dominic Fike, Denzel Curry, and the budding L.A. singer-songwriter Deb Never.

“I’m very big on family, and everyone I work with is close to my heart,” Slowthai says. “And working with people you’re close with, they’re gonna tell you when something’s shit or something’s good.”

As much as Tyron is an exploration of self, crafted during a time when it wasn’t exactly difficult to slip into deep solipsism, it’s very much a product of a community. Slowthai recalls a moment during the summer when conditions were safe enough for him, Kwes, SAMO, Krash, and Reid to get into a studio together. After months in lockdown, it was revelatory: “We just were just making noise like a band,” Slowthai recalls. “We never even finished anything — we’ve got like a two-week file, which is like a terabyte, just audio of us doing that. Just making noise.”

There’s one more element to the “Shoetown” mentality that permeates Northampton, and it speaks to what Slowthai has already achieved over the past few years, and what he’s aiming to take further with Tyron. It speaks to the idea of community, solidarity, and the way we all need each other if we’re going to survive — not just this pandemic, but everything else. it’s the reason people still converge on Northampton for a pair of shoes. “You’re creating something for people to last,” Slowthai says. “It’s not like a pair of trainers. A good pair of boots will last you a lifetime.”

You’ve said in interviews that you plan your albums in advance, and you thought Tyron might be your third instead of your second. What kind of album did you put on the backburner, and why’d you decide to make this one now?

I wanted to play on the irony of life. My first album was like a social commentary, and then I wanted to go into different characters and make something like a TV show. But the music for that, we need to get there — I can’t just jump to it straight away. And especially with being locked down, and mental health being a thing I was struggling with, and others were struggling with, I felt it was more pressing to talk about that than build an alternative reality.

Why did you split the album into two parts?

I love making the heavy shit that’s gonna make people angry and wild out [laughs]. But I’m probably better suited to make music that’s not that angry. I’m just at a different point in my life where I’m not as angry anymore, so it’s easier for me to write softer songs and talk about actual issues of my life than just do the hype shit. I just wanted it to be like, these are two different sides, two different types of people.

There’s moments where you get frustrated making [harder] stuff because it’s just a certain pocket. Be it based on tempos, speed or rhythm, there’s only so much you can do with it, there’s only so many pockets. Whereas the softer shit, there’s fucking endless pockets.

Were there any artists you were drawing inspiration from while making this album?

Weirdly enough, Jay-Z — more so for flow, wordplay, and delivery. I’ve always appreciated that from being a little kid when my uncle was playing it. I feel like there’s a lot of anger even when he’s doing the soft stuff. A heavy inspiration for me is Alex Turner from Arctic Monkeys. Thom Yorke. Eliott Smith — but that’s a weird one because it’s not like you can hear any influence from it. I suppose everyone I’m influenced by, it’s not like I’m trying to imitate them. What inspires me is the way they’re talking, the emotions they’re hitting, how they’re getting the message across. That’s why I think my inspirations come a lot from more band-oriented music. Like with Radiohead: “You do it to yourself, you do, and that’s what really hurts… ” That shit, to me — I want my writing to be as great as that.

What you were describing earlier, in terms of cultivating a family of collaborators, sounds not so far from a traditional band. Are you seeking that as well?

When we were making the album, it wasn’t like, “Yeah, get the big fancy studio with a big mixing desk that we’re never gonna use!” We like doing it in our houses, or someone will have their own studio. I used to think music was a really isolated process. I just wanted to be with my boys and enjoy it. When you’re first starting off making tunes, you’re trying to hype up your friends. You’re not great, you’re just playing around. Your friends are putting you on, they push you to be better. I want that vibe constantly.

Whose idea was it to slip in that sample of Mariah Carey’s “Dreamlover” on “Feel Away?”

You know what’s funny about that, everyone thinks it’s a sample, but it’s actually James [Blake] singing it. He was inspired by one of my lyrics, the Mariah Carey reference, and he was like, “Oh, if you’re doing that, then I can sing this!”

Deb Never has a great guest appearance on “Push.” How did that come about?

I met Deb in L.A. through Bearface from Brockhampton, and we just really got along. We call each other twins. My sister from another mister, if you will. [Laughs] She was there when I was drinking too much and was always like, “This isn’t the way.” Just someone who looked out for me, who always had my best interests. When I had this song, it was only one or two people I wanted on it, either Bearface or Deb. Deb just came through with the tone, man. She hit it. You meet people and you connect, and I feel like Deb’s gonna be there til the end.

Has meeting people been one of the better parts of all the traveling you’ve done the past few years?

I’ve always been a weird person who would bounce from group to group. I always felt like an alien or something. And then traveling, you meet people who are just as fucked up as you! And you’re like, “Yo actually, I’m not alone!” [Laughs] You meet that person for five minutes and it feels like you’ve known them your whole life. That’s the most important thing, and that’s why it’s important to travel and see the world, because you don’t know what’s out there, or who’s out there. Without it, I’d probably have never made friends and be this moody, lonely, fucking musician or whatever [laughs].

After all that travel, what was it like coming home to Northampton and making this album? Did being in this familiar setting offer any kind of clarity?

Yeah, we’ve all got that safe haven. You can be as honest as you can with your family. My mum’s one of my best friends, so I can come back and be like, I’ve been feeling like this. It’s nice to go back to where everything started and be in the same place and the same position. Because traveling all the time, it’s inspiring, but you can veer off and start doing things that other people do. But I don’t want to be talking about how I’m living this fucking life — I’ll end up making pop and being like, “Yeah, I’m in the Hills, I’m in the Valley! The sun’s shining! Life’s so great!” Because it’s not [Laughs]. And when you’re traveling, it feels like another life. You don’t feel like you’re taking it all in. You see pictures of a crowd, and when you’re there it just don’t seem the same, it don’t feel real. When you come home, you remember, I’m from here, this small place. Stuff like that makes you appreciate it, and I think that helps writing. It helps knowing, this is where I’m from, and this is where we’ve got to, and this is where we can get to.

Skepta appears on “Canceled,” which seems to be about the NME Awards. Tell me about your relationship with him, and how someone with his stature helped you contend with that moment, both in life and on this song?

He’s not like a mentor, but everyone’s got that person who can tell you, “Yo, don’t worry about this.” There’s so much self-doubt; I believe we all have it, even if you’re in the best position in life, or the worst. Before I made music, he was someone I always respected and wanted to be on that playing field with. You need to be around people that teach you, because if you’re always stuck around people who don’t have no understanding of what you’re doing, you’ll never learn, you’ll never grow.

I was in my head a lot [after the NME Awards]. When you’re not a certain way and people tell you who you are, you doubt yourself. If you’re fully against stuff and people are saying, “That’s you” — you can’t fathom it. So I’m sitting there, I’m in a dark head space, and he’s like, “This isn’t your defining moment, bro. Use this. Come out stronger, come out harder. Show the world what you’re about. Fuck all that worrying. Just be you and live your life. It’s rock & roll, you’re a rock star.” From that, we just banged out that tune. It was like being the kid again — you’re all in a room, bouncing ideas and flowing. It’s one of them tunes that’s — I don’t know — it’s like, fuck all that shit, I know who I am and I know what I am. No one can tell me any different. No one can change the course of my fate based on their views and opinions. I’m not about that. I’m here to change things, I’m here to make things better and I’m here to lead people to a brighter future with optimism.

There’s a saying that you have your whole life to make your first album and six months or a year to make the second — did you feel any pressure like that?

As long as you’re being honest, putting your heart and soul into it, it doesn’t matter. It’s like when you go to therapy and they say, “How you’re feeling, write it down, so you can get a clearer picture.” So you bang it all down and you read it, and you’re like, “Oh fucking hell.” And I feel like making music’s the same way. You just have to get it out. And if you’re not being honest, you’re not gonna feel it; but if it’s your truth, you can’t really go wrong. You can sit there and go, “Let me re-write it.” But then you’re taking the rawness out of it. Just keep it moving, keep making songs. I would rather be a David Bowie or a Daniel Johnston than a polished rapper.

The political commentary was at the forefront about Nothing Great About Britain, but it’s also personal in ways that echo on Tyron. How do you think those two records are in dialog with each other?

It’s the growth, innit? Me being a boy, me going into manhood. You can hear it in my tone, in my voice — the aging, if you will. It’s my journey, how my views differ, how things change. I believe in life we’re all a contradiction. Life is about contradictions. At one point you believe this and it’s the God’s truth. At another point you’re like, “How could I believe this? What the fuck was I thinking?” Later on, you’re probably gonna tell your kids, “When I was your age, I fucking did this once, and I couldn’t believe what I was doing!” [Laughs] It’s just the way of giving your experiences and helping people learn from them, or showing them they’re not alone in thinking or feeling these things.

There’s a line on “Vex,” “Never been the boy/I was a grown man” — you’re obviously doing a lot of growing now, but do you feel you’ve had to always be older than you are?

I think in every generation, if you’ve not been coddled your whole life and given every opportunity on a silver platter, if you’ve had to work — they beat being a kid out of you so fast. You should remain as young as you can for as long as you can. But growing up and coming from where I come from, you’ve gotta grasp it with both hands. I always had thoughts of providing for my family, lifting people up, and I suppose that made me want to grow up faster than I should have. I didn’t want to play with an action man and Lego — I wanted to be out with the older kids making money. But as I’ve gotten older, I wish I stood in the moments of playing games and Pokémon cards and GameBoys and doing that shit for as long as I could. As long as I possibly could.

Do you feel like you can tap into that a bit more now at least, both with quarantine and the success you’ve had?

That’s what I’ve been doing! I did go buy some Pokémon cards, because my birthday was the other day [laughs]. I was watching all these kids on YouTube doing it, and I’m like, “This is so sick, I wish I could do it.” And I was like, you know what? I’m not gonna spend $40,000 on a box of Pokémon cards, but I will go buy some packs, open them and get that nostalgia. Just playing games, joking around, being cute and shit, being weird. I’ve been stewing in that. Video games until stupid hours in the morning. Eating sweets, running around, playing football.

“Play With Fire” ends with this brutally honest conversation with yourself. What was it like writing and putting that on tape?

Everything I say at the end of that I actually tweeted. I’ve been doing this thing for ages where, rather than writing an idea in my notes, I just write it on the internet [laughs]. There’ll be some things I should keep to myself, but if I’m feeling shitty and something pops into my head, I’ll just tweet it, because who knows? Someone else might be feeling this exact way. When I was recording that song, I literally pulled up Twitter and read it out as sporadic as I could, so it had that stuck-in-your-head feel, when you’re battling with your mind. It’s all things we place upon ourselves, fighting with your insecurities — that’s the fire, that’s the thing you’re playing with, your own demise. Because it’s easy for us all to sit around and say, “I’m happy sitting here forever,” but you’ve actually got to get up, make it happen and live your life.

“ADHD” closes the album and brings back some of those harder sounds, despite being on the softer second half. Why’d you choose to end the record that way?

I felt like that was the summary at the end of the book: what you’ve realized, how you’ve felt. On the whole project, I don’t think I’m that soft-spoken as I am in the first part of the song, but when it gets to the end, it’s my anger, like the last push — all them feelings, just getting it out. And being ADHD, this project is for the generation of kids coming up now that are hyperactive, can’t focus and feel like they don’t know where they fit in or who they are. This is my project for them. That’s why everything sounds choppy.

I’m becoming more confident and comfortable knowing I ain’t gonna sound like Future, or I ain’t gonna sound like Jay-Z. I’m not gonna keep you here on this one level. I am off-kilter, I’m weird as fuck — this is me. This is Tyron. It’s the best way for me to put my personality and the real me into song form for people to get it. There’s probably a billion kids that feel exactly the same way, and I just hope they’re taken with it and like, “Yo, this is for me.”

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.