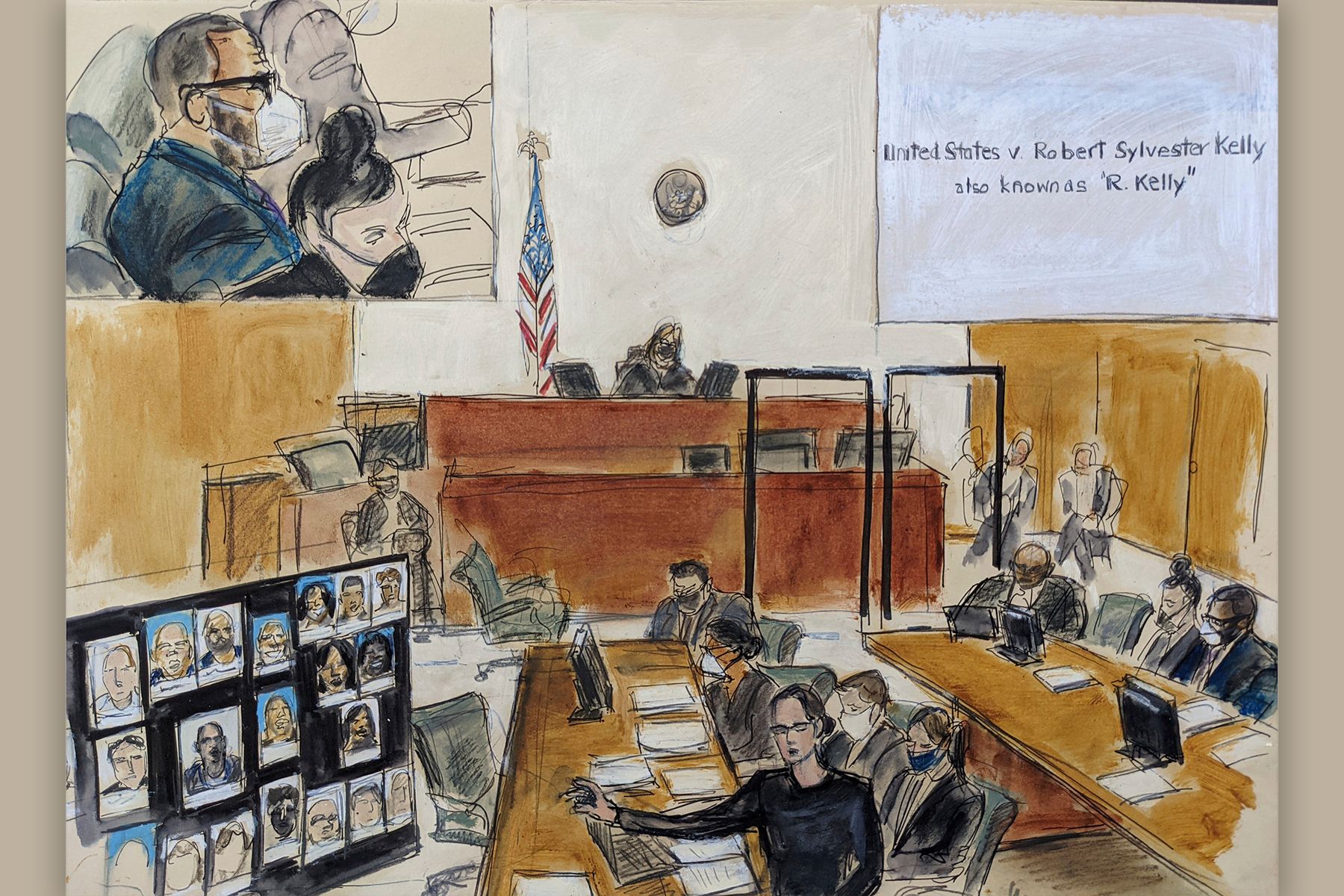

Prosecutors’ Closing Arguments: R. Kelly Used ‘Threats and Physical Abuse to Dominate Victims’

The trial of R. Kelly in Brooklyn crawled, dragged, and inched nearer to an end on Wednesday afternoon, as the prosecution started its closing arguments.

Kelly “used lies, manipulation, threats, and physical abuse to dominate his victims,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Elizabeth Geddes told the jury. And he relied on “his money, fame, and persona to hide his acts in plain sight.”

Closing arguments started more than a month into a trial that has involved dozens of witnesses and hundreds of exhibits of evidence. That’s a heavy emphasis on “started”: Kelly is accused of one count of racketeering with 14 underlying acts — he has denied all charges — and on Wednesday, the prosecution worked painstakingly to present proof for each of those acts. This was a wildly slow process: Over the course of the afternoon, Geddes only got through five of the 14.

Not that prosecutors have an easy task; they’re effectively rebuilding a mountain of evidence in just a few hours to make one final argument so it stays fresh in the jurors’ minds for their final deliberation. Geddes’ comments were an avalanche of names, dates, exhibits, floor-plans, and phone records. She toggled back and forth between timelines — frequently relying on phrases like “let’s rewind” or “we need to back up again” — as she attempted to demonstrate patterns in Kelly’s actions that might not have been visible during earlier testimony. The performance was at once intricate and repetitive, an overwhelming data dump that was effective if also numbing.

The most straightforward arguments came earlier, before the prosecution burrowed into minutiae. The point of bringing the racketeering charge, Geddes noted, was that “when someone commits a crime as part of a group, he’s more powerful, more dangerous.” Kelly was “more than just a part of an enterprise,” she asserted. “He was a leader, and he used the others to achieve his goal.”

To help illustrate the extent of Kelly’s enterprise, the prosecution prepared an old-fashioned visual aid: A board full of photos — featuring the singer’s business managers, personal assistants, runners, security personnel, drivers, and more — arranged with Kelly at the center. “Working for the defendant was not like a normal job,” the prosecutor insisted, noting that former employees had testified that the experience was “a hostile work environment” and compared it to “The Twilight Zone.”

Then Geddes hit her main theme: Kelly “was able to carry out racketeering acts… because he had the enterprise at his disposal,” she asserted. Some of his employees actively helped him in myriad ways — by distributing his phone number to underaged women at concerts, driving women to appointments with Kelly, keeping them under surveillance, and even bribing a government employee to make a fake ID for an underaged Aaliyah. Other employees helped Kelly’s efforts just “by turning a blind eye,” according to Geddes. She repeatedly returned to the same point: “Without [Kelly’s] inner circle, [he] could not have carried out” his alleged crimes.

Geddes then returned to those alleged crimes, one by one, accusing Kelly of “groom[ing] girls and boys for sexual activity despite the fact that they were too young to consent.” The first five counts for which she worked to establish proof on Wednesday related to bribery (to obtain a fake ID that claimed Aaliyah was 18), child pornography (videotaping sexual activity with a 17-year-old in Chicago), secret confinement (an aspiring radio broadcaster testified she was locked in a room in Kelly’s studio for days), crossing state lines for illegal sexual activity (that same broadcaster, who lived in Utah, says the singer’s minions flew her to meet Kelly in Chicago, where he engaged in sexual activity with her while she was unconscious), and coercion of a minor into illegal sexual activity (when a 16-year-old girl told Kelly her age, she recalled him responding, “what is that supposed to mean?”).

Earlier in the week, the judge said she hoped to hand the case to the jury by Thursday, though it’s hard to imagine this happening if the prosecution moves at the same pace as it finishes its summary. The defense still has to present its closing arguments as well.