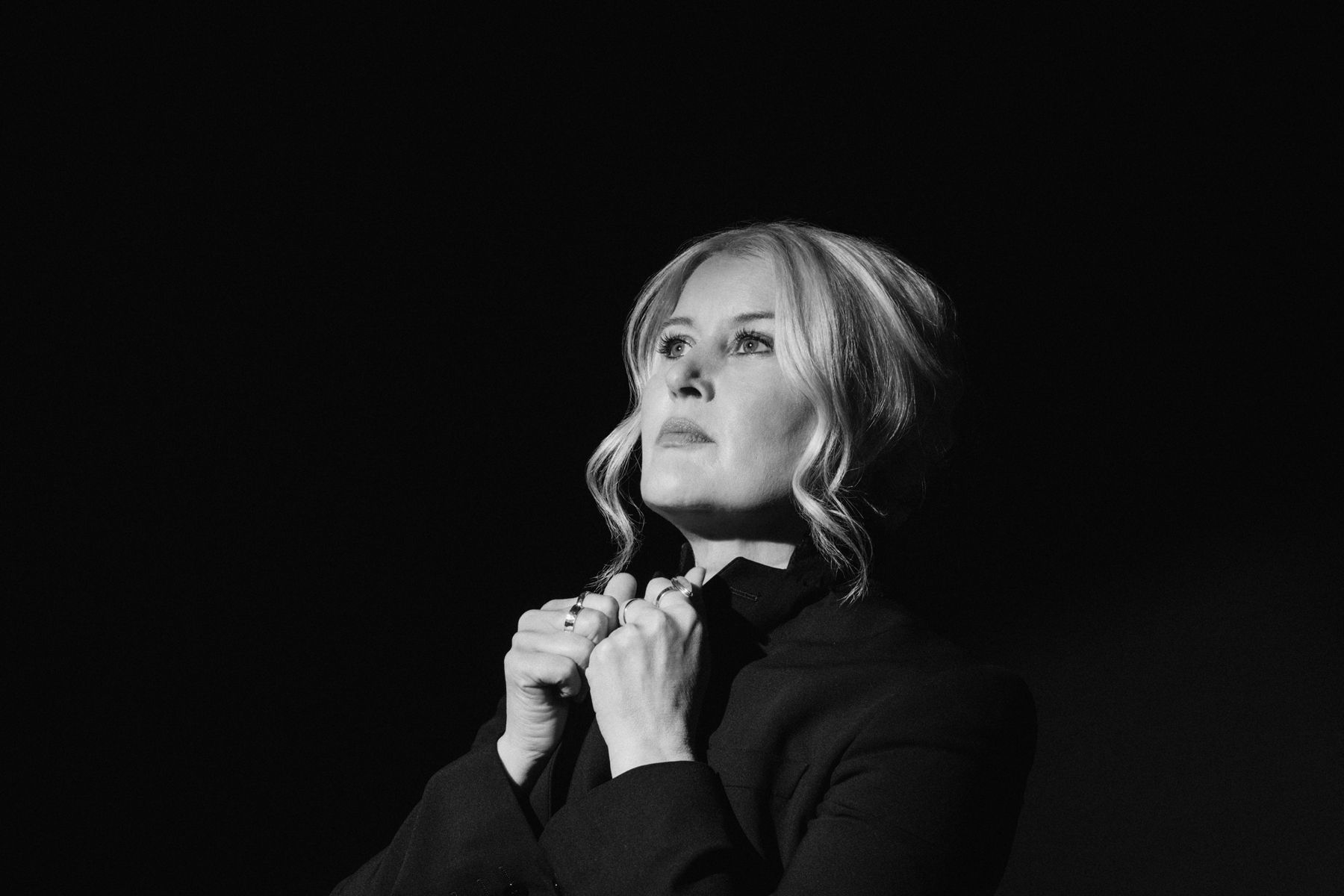

Paula Cole on New LP ‘American Quilt,’ What She Learned From Emmylou Harris

When Paula Cole released her 2016 album, Ballads, a double LP of folk and jazz standards, she felt her work was incomplete. “It didn’t sit right,” the singer-songwriter tells Rolling Stone over the phone from her home in Massachusetts. “I needed it to be more of a diverse patchwork, incorporating my roots as a typical American and also as a daughter of a professional musician. I’ve been in this melting pot of music since I was a little girl, and I needed the album to reflect that diversity.”

American Quilt, out May 21st, is the fondue of Cole’s melting pot, blending a variety of genres that include jazz, folk, and country. Cole takes on classics like “Black Mountain Blues,” “Nobody Knows You (When You’re Down and Out),” and “What a Wonderful World,” creating a patchwork of American music. The album also includes one original song, “Hidden in Plain Sight,” which is about quilts women made that provided clues to slaves in the Underground Railroad.

Cole spoke with us about the LP and looked back on her career, from her friendship with Emmylou Harris and touring with Peter Gabriel to “Where Have All the Cowboys Gone?” fame and feminism in the music industry.

How has your quarantine been?

Thanks for asking. For a while, I felt like a matriarch at a B&B because I was taking care of young adults — my daughter and my stepson and my niece. But now they’ve all gone off to college and I’m going through empty-nest, so that’s been a very interesting psychological life shift. I also have my parents. I’m in their life and help take care of them. So it’s been very much about family — hunkering down and guarding and protecting and working for those who love most.

And thank God for the music, which really forces me to still be connected to people online. But having this “Sunday Evening Song,” I kind of put it on myself because I realized, “Oh, my God, I’m such an introvert.” I test so highly as an introvert that if I were to go into this pandemic feeling even more deeply into myself, that could be a recipe for disaster. So, thankfully, I can make music at home and I think I’m managing quite well. I take a lot of walks. I learned to knit [laughs]. I also am a visiting scholar at Berklee College of Music. I’m still able to have a job and I really know how fortunate I am.

How did the album come together?

The first part happened in 2016, when I recorded my Ballads album. It’s a bit of a long story, but I started as a jazz singer. I’ve loved jazz my whole life. That’s why I went into music — I thought I was going to be a jazz singer. And then a lot of those standards felt very ill-fitting to me, so I ended up writing my own truths, and my career happened through my own songs. But often I think about the catalog I want to leave and I even have a meditation of being on my deathbed and looking back. That’s not to sound morbid. It’s more just an exercise in awareness. I think, “What did I do in my lifetime?” and I often ask, “Am I doing enough?”

So I always have needed to make an album of standards. I made Ballads, and I was so pent up that we made 31 songs in five days. I released it as a double album, and I was sitting on a lot of great tracks that I felt were very strong. So I used that as a basis, but it didn’t sit right. I needed it to be more of a diverse patchwork, incorporating more of my roots as just a typical American and also as a daughter of a professional musician. My dad surrounded me with jazz and folk and country, and I needed to address all of these genres. I’ve been in this melting pot of music since I was a little girl. I grew up in an extremely musical household where everyone played multiple instruments and my dad was gigging on weekends, and I needed the album to reflect that diversity.

Also, I hate labels. I hate genre classifications, which tend to narrow music for marketing, which is for money, and it’s usually about race or age or gender. It’s all the bad things. And that’s what non-musicians do: They classify the music. So I’ve always been rebellious against labels, and it’s always been hard to describe my music. At some point I just threw my hands up and said, “Well, time will tell, and it’ll just be me and it’ll just be my music. Even if I’m popular one day and I’m not popular in the next year.” I’ve been on four or five major labels and I’ve been an independent artist. I just keep going. Because I worship at the altar of music, I keep picking myself up. Because I love music. I need it as a therapy, as a reason for existence.

How did you come up with the concept for American Quilt?

I went into the studio in January 2020, right before the pandemic hit, and cut “Wayfaring Stranger,” “Shenandoah,” and “Black Mountain Blues,” which I learned through Bessie Smith and also Janis Joplin. Now we’re now in the pandemic, and I was thinking of calling it American Quilt because it truly was a patchwork, and [because of] my mother being a visual artist and surrounding me with her work. Quilting was a longtime part of her heritage.

In doing more research on quilts in America, what really stunned me was coming across stories. Some people dispute their truth, but I believe it. It’s a whole history of the concept of slave quilts and how often they were created by women, and women’s work was considered trivial and overlooked. They were making quilts that served as clues and guides to access the Underground Railroad. So I realized, “OK, even though this is not my story to tell, it’s not being told, and I feel like we need more consciousness about our past, who we are.” It’s one of my important life missions to be in the conversation of race. My daughter’s biracial. And also, I’m a singer of American music. It’s a blend of so many voices and cultural influences. So I need to be in on that conversation. And if we’re going to be anti-racist, we have to bring these subjects to the table.

The lead single “Wayfaring Stranger” leans into Americana. Why did you decide to record that one?

“Wayfaring Stranger” I knew best through Emmylou Harris’ version on Roses in the Snow, because that album has been pivotal for my life. I think it was Emmylou’s version that was deep in my DNA. One day I was on NPR and I was at soundcheck, and I found my fingers moving in the shapes around C minor on the keyboard, and it just brought me to this place. It was this weird lightning bolt, like, “I need to do this song!” It just flowed really well in the studio that day. It was a blessing.

And Emmylou, I’m so glad to be able to even just talk about her, because I think she’s one of those important voices for America. And she’s also been an important person to me. I remember when my career went up very quickly and I didn’t like the way it was going. I needed to return to my roots and have personal relationships again and take a break from the music business. So I took about a seven-and-a-half year hiatus, and in that time, I did this singer-songwriter [concert] in the round in Nashville that she was in as well. I confessed that I was thinking about leaving the music business and she had a very tender, wise, and motherly moment with me, saying, “It just happened too fast. You can’t quit.” She said, “I’m lucky because mine’s been this nice even plateau.” So I’m partly here because of those words.

And she knew me too from Lilith Fair. She sang “Carmen,” and I sang on “Green Pastures,” this other beautiful song from Roses in the Snow. I would go on her set and sing that song with her. And I just love her so much. I love her for her musicianship and for fostering community amongst musicians, including someone like me, who was a bit written off as a pop artist.

The album also contains “You Don’t Know What Love Is,” which has been covered by everyone from Miles Davis to Chet Baker. How did you approach the songs knowing they all have so much history?

Having been in jazz, it’s a heavy mantle. You’re inheriting the music from your elders, and you try to revere it and love it and then send it on to those younger than you. It’s multigenerational. I was really most influenced by the [John] Coltrane version. We really acknowledged that particular recording of it in that its front half is rubato feel. It ebbs and flows. Even my phrasing was very influenced by Coltrane. I’m doing weird things with my voice and it’s kind of melismatic.

A video I’ve been watching over and over in quarantine has been “In Your Eyes” from Peter Gabriel’s Secret World tour. I even have all the dance moves down. How did touring with him help you grow as a performer?

He was a big influence on me. I felt like when I heard “Don’t Give Up,” I needed to sing that song. I just loved it so dearly, and it’s just miraculous that it came true. I’m also a huge Kate Bush fan. I thanked her when I won my Grammy. Working with Peter and his band was a beautiful affirmation. I’m there with my heroes, and I knew the music inside out.

It was 1993. Peter heard Harbinger and he loved it. He left me a message on my voicemail just asking me point-blank to join the tour. I think Sinéad O’Connor had stepped out. I flew to Mannheim, Germany, and I had a very short soundcheck. We sang “Don’t Give Up” and maybe one other song. So that night I was thrown out in front of 16,000 Germans.

We didn’t rehearse dance moves, and that video was shot, like, less than a week after I joined. So it was time to sink or swim, and I swam because I was a musician and I was a huge fan of Peter Gabriel’s and I loved the music. So I learned a lot from Peter. I also learned that I wanted to be my own artist. I didn’t want to be a background singer. I didn’t want to be in somebody else’s touring company. I needed to be my own feminist boss and have people around me that were supportive of that [laughs].

The music industry has improved for women, but we still have a long way to go. How do you look back on 1997 and that period of fame?

It was a very tumultuous time, and like Emmylou said, it happened very fast for me. It was constantly shocking for this introvert, and it was shocking that “Where Have All the Cowboys Gone?” became such a big hit. And then it was shocking that half of America didn’t quite understand the irony of the feminism in it. I felt a bit misunderstood, because it probably couldn’t get more feminist than me. So it was pretty ironic that there was misinterpretation.

I was just being me. It was free and strong. And how wonderful that some of those women have been allowed into pop. But, yeah, after the Grammys, there was just such meanness aimed at me. It was really harsh for having hairy armpits. Who cares, you know? I just honestly hated it. I hated the music business and I hated what my career became.

So I made my follow-up album [1999’s Amen], which definitely took a different tone. It was less art rock and moving more into neo-soul, and I’m still proud of that. But in came Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera, and it was very anti-Lilith. And I was probably the most darkhorse feminist of them all [laughs]. So it was not good timing. I thought, “Fuck this,” you know?

So I left, and I wanted to renew myself. I needed a reset. When I think back to those times, it was electric. It was intense. It was shocking. It was disappointing. It would have been better if I could have had more of a plateau and a longer, slower build and people had seen me live more, just to see that aspect that I’m, like, a performer, not just so much about hits. But that’s all from the past. I’m constantly coming up against that and I’m grateful for my hits, because they allowed me that hiatus. They allowed me time, and they still do. But I think of myself more as a catalog artist and legacy artist, and I think finally people are understanding that now. It’s interesting to see a younger generation. They find my music and they don’t have that judgment that came to me after the Grammys, and they’re excited about it. I’m happy. I feel like it’s the story of the tortoise [laughs].

Tell me about recently rerecording “I Don’t Want to Wait,” the Dawson’s Creek theme.

I rerecorded my two hits in 2015. I will not allow any usage of the original recordings because I got screwed with that deal and I’m still being screwed by that deal. It’s just extremely unfair and I’m not going to do that. So I rerecorded them and now the rerecords get used. Actually, because of the reaction from fans of Dawson’s Creek, Sony TV is finally going to use my song again. We’re in negotiation for that, and they’re going to use the rerecord. So that feels positive too. I just said no, and I’ve been waiting it out. Having faith and staying the course and keeping making truthful music. Time will tell.

American Quilt will be released at a time when tours are being scheduled again. Are you thinking about doing that at all?

I had a tour built for the fall of 2020, and, of course, it was all canceled, and now it’s being scheduled for fall of ‘21. So I have venues booked and I’m doing some shows with Madeleine Peyroux as well, and we’ll see if they happen or not. By then if they’re happening, people will have heard American Quilt for a few months and know the songs better. So that’ll be nice. And if not, I’ll just tour when I can. It’ll happen eventually.