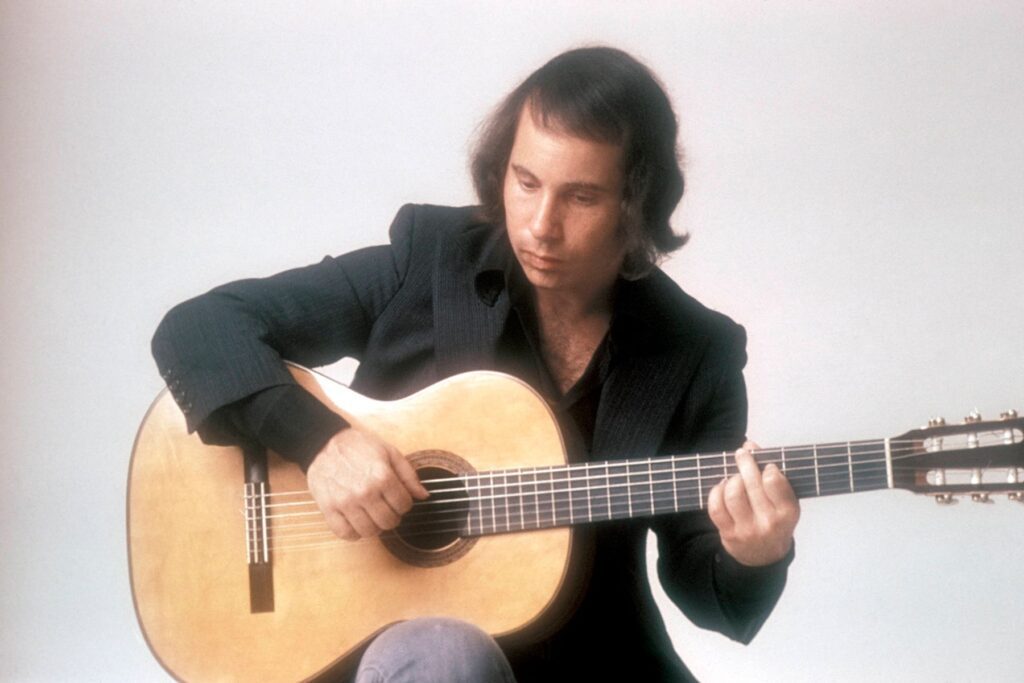

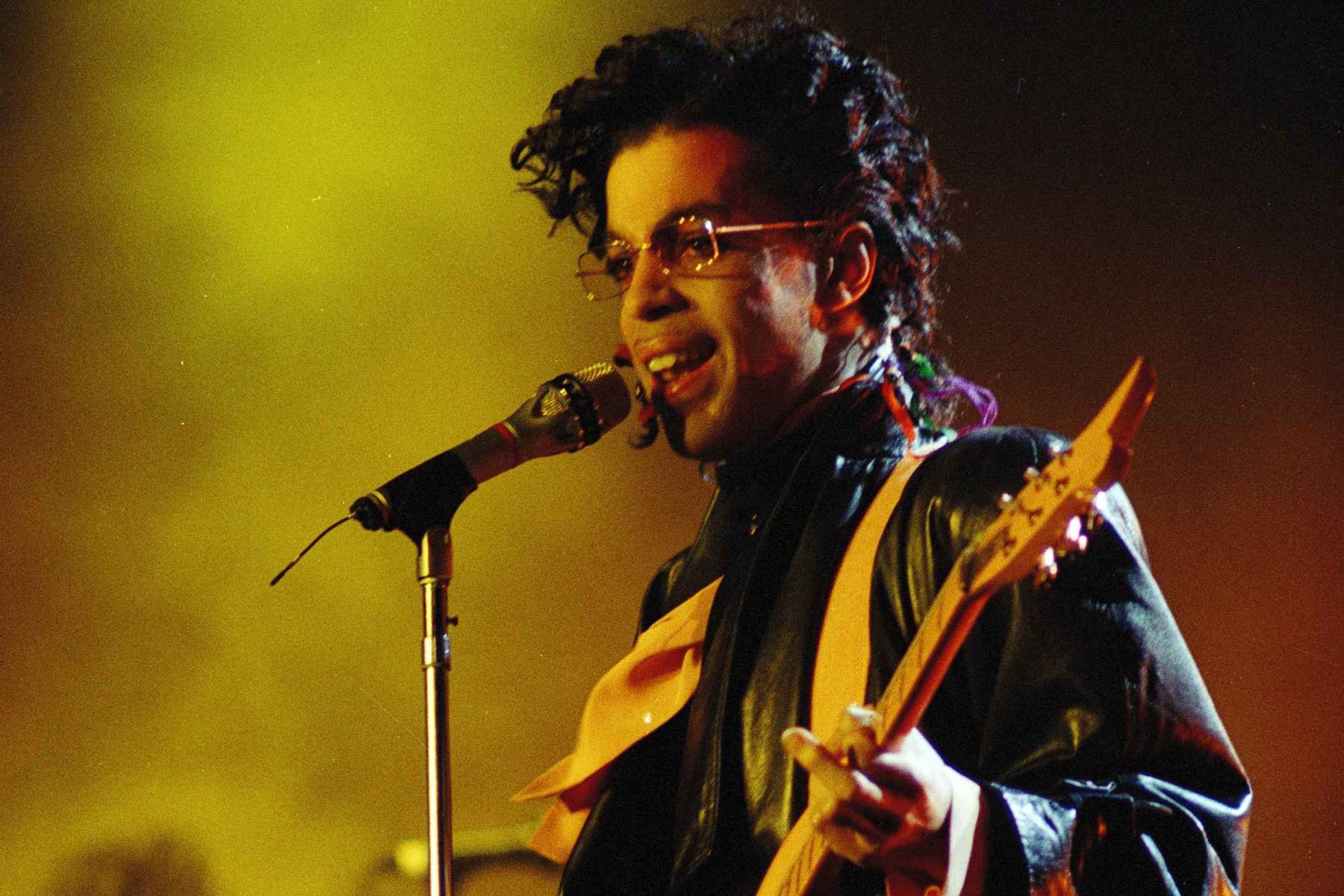

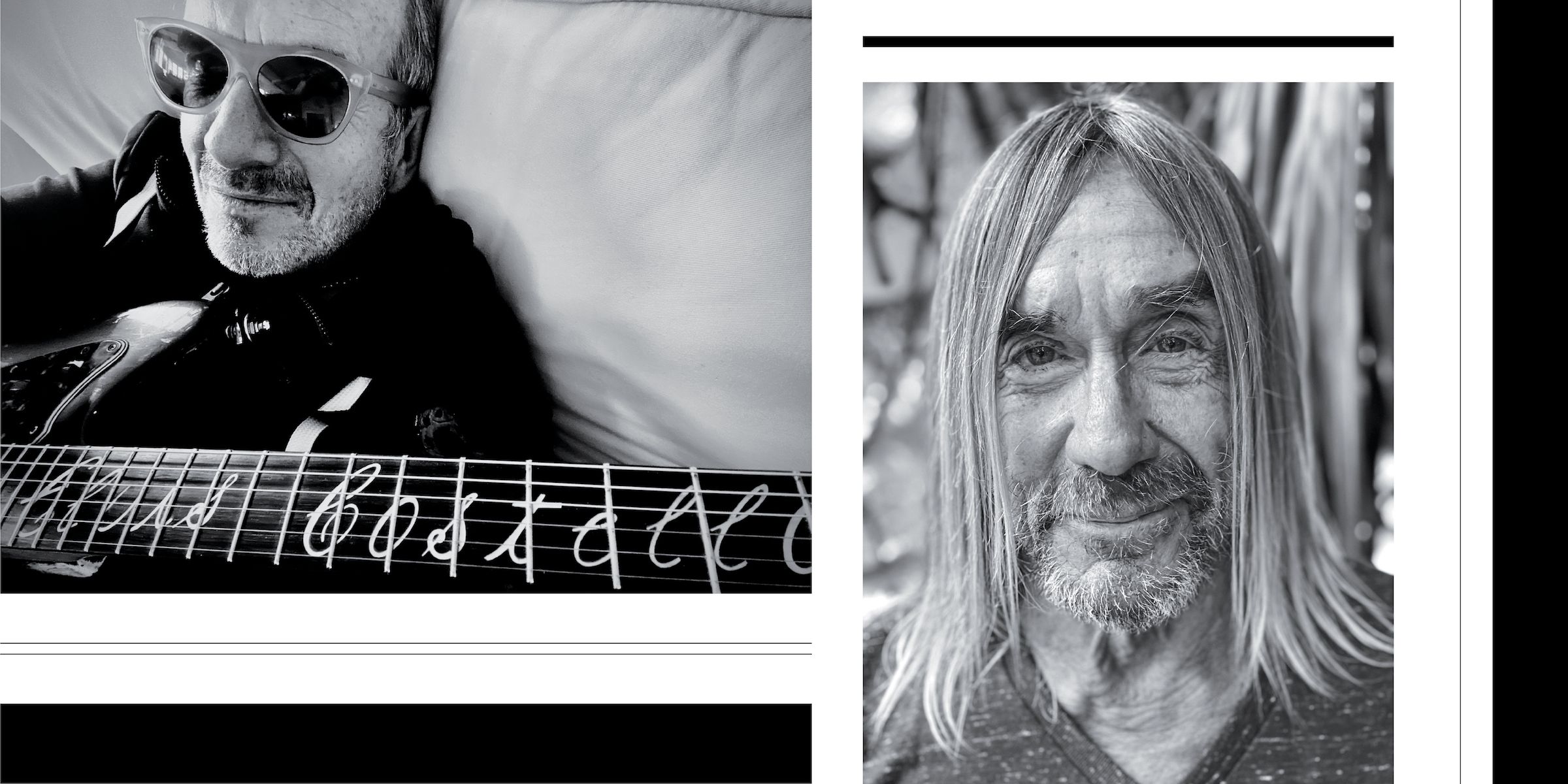

MUSICIANS ON MUSICIANS Iggy Pop & Elvis Costello

MUSICIANS ON MUSICIANS

Iggy Pop & Elvis Costello

The old friends on surviving the Seventies, why most hard rock is overrated, and staying in touch with their iconoclastic inspiration

Elvis Costello was less than 24 hours into his first American tour when he met Iggy Pop. It was November 1977, and the former Stooges frontman was playing at the Old Waldorf in San Francisco when a bleary-eyed Costello, fresh off a flight from London, wandered into the venue just in time to see Iggy sing “The Passenger.”

“My memory of it was I was slightly scared,” Costello tells Iggy. “At one point, you got this tiny chair and inserted yourself into it. It was kind of like if you took Marlene Dietrich and put her in a rock & roll band.”

When the show was done, Costello was ushered backstage for a quick chat. “You put your arm around me and said, ‘Just take care,’ ” Costello continues. “You were very kind, and I’ve never, ever forgotten it.”

It was the start of a long-distance friendship that culminated last year, when Iggy recorded a French-language cover of “No Flag,” from Costello’s new LP, Hey Clockface, which we are premiering today. Right now, Iggy is at his home in Miami and Costello is in Vancouver. They greet each other warmly once the Zoom begins (Elvis calls Iggy “Jim”) and spend the next 90 minutes talking about each other’s greatest music, high and low times in the Seventies, and their lives during Covid-19.

Costello: I read about the Stooges in the paper, but the real starting point for me came when there were a lot of bands trying to sound like you when I started making music in 1976 and 1977. Some of them were actually playing Stooges songs. You had two records that caught people’s imagination [1977’s The Idiot and Lust for Life]. Everybody was talking about all of it.

Pop: [You] had something out in the late Seventies in England. It had two things that struck me. One was a whole lot of facility with the melody. I was like, “Jesus, this geezer can lift a hook.” The other thing was the use of the keyboard and the organ by [the Attractions’] Steve Nieve. That really struck me. Wait, didn’t we have dinner at a curry joint once in London?

Costello: That was later. Good memory.

Pop: We had dinner and talked about music. You had the curry and a big lager.

Costello: When we were teenagers, my friends and I would go to a pub where they played music, and then we’d order the hottest curry we could eat. It was a badge of honor. The first time I suggested that to an American, they looked at me like, “Are you crazy?” I guess you’d spent some time in England and maybe in the company of English people that have done that.

Pop: I used to love the newsstands in England. I’d get very excited on Wednesday morning, when you’d get up and they had the music papers. Sounds, New Musical Express, Melody Maker. Each one would have their own slant. Sounds was the cheap one, and it was pretty easy to get in there.

Costello That is definitely right. I think I got my first mention ever there. That happened once they put these glasses on me and changed my name. It was a little like Clark Kent in reverse. I appeared in Sounds, and I couldn’t believe it. In one minute, I was working in an office. In the next minute, I was on the cover of Melody Maker for being arrested.

Pop: The busking!

Costello: We did a publicity stunt to try and get arrested. The policeman came along like, “You have to move along, sonny.” He picked the wrong guy. There was no way I was walking away. I think we might be slightly wired that way. If you say, “Do that,” I’ll do this. They hauled me off.

Pop: When I heard your music, I felt like you were the only thing coming out of the U.K. that wasn’t going along with the I’m-a-monster-with a-guitar-riff thing. The whole guitar riffage was going up and up and up. You were either that or, no offense to her, you were Lulu.

Costello: I actually like Lulu better!

Pop: I love Lulu. But you were either doing schlock or you were doing this thing that every six months was getting more stupid and dull. Being English, you know about this — when you don’t have much money, you save the tea bag for a second squeeze. That’s how rock was getting at that time. You came up with something different.

Costello: Even after all these years, people say to me, “You came out of the punk time.”

Pop: But it wasn’t punk. It was just that time.

Costello: The Pistols called themselves the Pistols because that was a great name. It was probably a better name than it was a group. The Clash were the Clash. I had the blessing or the burden of this crazy stage name. But there’s a person behind that name, and you just try to keep that person from getting too injured by the process.

The squeezed-tea-bag thing about rock & roll is so true. Elvis’ first record doesn’t have drums on it. Jerry Lee Lewis doesn’t have bass, because that’s all they had, all they could afford. Johnny Cash’s first record didn’t have drums. The rhythm was coming from guitar. Did you need it? No. Does anyone think it doesn’t rock? No.

Pop: Little by little, you needed more. You needed a bigger drum set. You needed someone that could wail [screeching banshee voice], “Whoaaaaa, baby!” And all that.

Costello: [Sarcastically] I can’t think who you are speaking of! Who are you referring to?

Pop: That one group led to groups in the States like Cinderella.

Costello: It’s so horrendous. The first time I ever met Robert Plant was at a benefit show in 1980. I went right up to him. I was full of drink and drugs, and I got right in his face, and he thought I was going to say hello. I just said, “Stairway to Heaven,” in my most sneering voice. Back then, there was all this ridiculous rivalry between the generations, when we were only actually four or five years apart. We saw it as the old folks’ music.

Pop: In rock & roll, five years is a generation. For me, [starting a solo career] was somewhere below hopeless. You knew you were not going to get on the radio, and in America, the business was starting to get taken over by the overweight muscly guys with the baseball caps who later took over the whole biz. It was either them or you had the “Rock Goes to College” magazines. It wasn’t going to happen for me.

Costello: I read about all these rock clubs in those magazines. Suddenly I’m in the Whiskey a Go Go, and it really didn’t look that splendid.

Pop: You were a little late for that. You caught the tail end. We recorded Fun House in 1970 in L.A., and we went to play the Whiskey. We were staying in the same hotel as Andy Warhol and his entourage. They all came to the gig and sat in the booths in the back. You had the Stooges onstage, and there’s that dance floor. We had three little surfer babes with the hip-hugging miniskirts and the bell-bottom pants doing the surf dance. That was pretty special, because it didn’t really go with us or our music.

Costello: It’s so great they still did that dance regardless. We had a bunch of sneering people looking at us. We stayed at the Tropicana, too. That was still in operation.

Pop: That was the place.

Costello: I knew that strip pretty well. In one direction there was a car wash, and in another direction there was an IHOP. I didn’t drive, so I was really at a loss in Los Angeles. No buses, no subways. “Oh, that place you want to walk? That’s four miles away.” It was so mystifying to me.

Pop: I never really learned [how to navigate the music industry]. The Stooges started on Elektra. Jac Holzman was a record-store owner, that’s all he was, but he had good taste and a good education. Elektra got sick of us, and we moved to CBS [for 1973’s Raw Power]. Clive Davis was there. He wished he’d never signed us. And then RCA signed me [for a solo deal], because any project that David Bowie was doing, they wanted to be the ones doing it so he wouldn’t talk to other executives. By the time I got on Arista, it was a wonderful guy from England named Charles Levison. Then Clive Davis took control of the company, and the first thing he said was, “You did what?! You signed Iggy Pop! Oh no!”

Costello: There were all these horrible machinations around Raw Power.

Pop: Really bad.

Costello: The first edition of that album sounded like a copy of a cassette, with no bass, and that weird compression. The energy you can’t extinguish. It’s coming at you. But it must have been weird that a lot of people in England cited that record. Was it hard for you?

Pop: The good thing was there we were, taken out of Detroit, completely away from all our bad distractions. We had a place to rehearse, a place to write, and finally we had a good studio. We were able to make a really great record, but things started falling apart when it came to, “Are we going to be able to do a gig?”

Later, I became sort of like Colonel Kurtz. I tried to mix it the way I imagined it could sound. Finally, gently, it had to be taken away from me. James Williamson and I went in for two days with David Bowie in L.A., and we did a mix together. At that time, none of us knew anything about what mastering was. As soon as the needle went anywhere near the red, it was like, “Wow, turn it down!” We were the red.

Costello: Were you ever on any really eccentric bills early on — those crazy juxtapositions where you got Quicksilver Messenger Service, Freddie King, and Miles Davis at the Fillmore?

Pop: One of the worst bills I was ever on was the J. Geils Band, Slade, and Iggy and the Stooges.

Costello: Wow!

Pop: The last thing I remember is popping ’ludes in Peter Wolf’s hotel room after the gig. And then [Stooges guitarist] Ron Asheton always claimed that I was chased around the hallways by Slade’s tour manager with an ax. “I’m going to kill him!”

Costello: Sounds like a regular night around that time, really.

Pop: We were the band that a lot of rock acts wanted to avoid. People did not want to follow us. In 1970, right after Fun House, the Stooges played the Fillmore with Alice Cooper. That was when it was the old homemade Alice Cooper Band. They were singing about spiders, and they all had the matching spandex outfits, and they’d shake their hips like ladies. Alice had a little light show that he’d control with a foot switch. They were cool. At that show, the front row was occupied by these people called the Cockettes, who were early drag performers. They had Carmen Miranda banana hairdos and everything. They became part of the show.

I did one show later on at one of my lower periods at a place called Bimbos in San Francisco.

Costello: I know Bimbos.

Pop: Oh wait, the best one! This kills them all. One time, Iggy and the Stooges played a small place in Nashville called Mothers. This was when Nashville truly was Nashville. The other band was the Allman Brother roadies. They took one look at us during the soundcheck and started making loud comments like “Do you think they have pussies under those jeans? Let’s go to the bathroom and find out.” We thought they were going to beat us up. Then they stayed for our set, and they all came and apologized: “We didn’t know. You rock good!”

Costello: When we’d go into a town like that, we’d seek out the record shop and go, “Where are the records by groups from here?” I’d be in Akron and I’d get the Pere Ubu singles that I couldn’t get in London. You’d be in Boston and you’d get a record that was just in Boston. They’d be on their local label, just like we were. Texas was a little bit different. We’d play the Armadillo in Austin. The poster would have Mose Allison and the Flying Burrito Brothers on it. I didn’t know what decade I was in.

Pop: We did a lot of good bills in the early Seventies in Detroit. The Stooges got to open for the Who, Cream, Zeppelin. We saw Jimi Hendrix play to a converted bowling alley in Ann Arbor. I was six feet from him. The stage was eight inches high. Things were more easily accessible. There was usually some sort of egomaniacal nutter in each town that had some business sense, but also just wanted to do something cool. Music was a way in for some people.

Costello: I think something we learned from each other is fearlessness, particularly in recent times. You can make records in France, where you’re singing in French, or the record you made with Josh Homme [2016’s Post Pop Depression]. I saw you one night on the BBC when you were playing with those guys, and you closed the show with “Lust for Life.” You ran past the cameras and into the audience. I was like, “This is so full of joy, and it’s also the kind of music that the authorities usually say, ‘Let’s ban this immediately, because it’s going to cause some trouble.’ ” It’s still right there if you want it. I think that’s rock & roll. What we’ve been talking about is the danger of sticking to that first plan and not having another idea. It becomes harder and harder to have the surprise you felt when you made those great records at the beginning.

I went all the way to Helsinki to record these three songs that I began [Hey Clockface] with. The first is called “No Flag.” That should have been a clue right away. It shared one word and one letter with a famous song of yours [“No Fun”], but nobody spotted where it was drawing from, because nobody expects me to take a cue from you. I thought, “What don’t I need?” I have a bass player in my band, but I didn’t take him with me. Unlike you, I can’t play the drums, so I’m going to sing the drums. Even if it’s just three chords, you have to find a way to make that fresh.

There was a “toes right to the ledge” philosophical idea in that song, which I hear on a lot of your songs. I think of “Some Weird Sin.”

Pop: I thought of that song too when I heard it.

Costello: The line in that song “stuck on a pin” came to my mind. You reach that point in your career where there’s a version of you that is like a butterfly in a collection. You have to get off that pin. I love that song so much.

[Since the pandemic began] it’s difficult not to be able to visit my mother in England, who is 93 and not in great health. You worry. I have a son who is in London. I worry and want him to be safe. Things are a little bit more tense there. But for myself, I can only be grateful for the time and relative calm we’ve had.

I’ve had time with Diana [Krall]. Normally, one of us would be on the bus to a place like Wichita at this moment, and our boys wouldn’t be with us. That’s our life. I’ve watched her put a record together, which I never have a chance to do. She usually makes her mixes in the music room upstairs, and I’m working on things even newer than Hey Clockface.

Pop: I had a tour booked this year. And then “Bam!” It’s part of the summer gone. “Bam!” There goes the rest of the summer. And so immediately I have this huge muscle buildup. “This is what I do! Nothing stops me!” And then I developed a healthy fear of the virus for an old boy with a history of asthma and bronchitis.

I said, “All right! We’re going to reschedule!” I rescheduled the whole thing for 2021. And then one by one, as the months went on, this thing is not going to be predictable or doable in 2021 either. At that point, I made the decision to back out. But I would have these nighttime attacks of, “Who am I now? Who am I going to be?”

Costello: I know when I do come back onstage, it’s going to feel great. Imagine what kind of party we’re going to have!