Me and the Monkee: A Final Visit With Michael Nesmith

Me and the Monkee:

A Final Visit With

Michael Nesmith

As one 'Rolling Stone' writer got to know Nesmith over the past decade, the Reluctant Monkee surprised him again and again. By the very end of his life, the man who was legendarily disgruntled over the Monkees' prefab ways had come to love the band as much as anyone

When I stepped onto Michael Nesmith’s tour bus in Huntington, New York, on Oct. 28, the first thing he did was offer me some weed. I politely declined, as I did every time we sat down together, and asked about his health. The subject had been on my mind ever since I saw him at tour rehearsals early the previous month and was startled to find him gaunt and pale, unable to stand for more than a minute or two at a time.

“Don’t know,” Nesmith said between puffs on his vape pen. “Any health issues I have are trivial. And as you know, I’m a practicing Christian Scientist. I don’t go to doctors or the hospital.… But people keep asking, ‘Are you going to make it?’ Well, I don’t know what the fuck that means right now. Will I live to a thousand years old? I don’t think so. But I don’t know. Monkees are strange people.”

The Mike Nesmith I had seen in September didn’t seem like he’d be able to get through a single concert, let alone a 10-week tour. But after a very rocky couple of weeks where Nesmith stationed himself on a stool throughout the shows and freaked out the Monkee faithful with his droopy demeanor, he gained enough strength to stand throughout that entire two-hour Huntington gig at the end of October.

By the time the tour ended on Nov. 14 at L.A.’s Greek Theatre, just a few miles from the Columbia Studios lot where the Monkees were born 56 years earlier as a made-for-TV Beatles, Nez almost seemed like his pre-pandemic self, if a bit wobbly, gleefully belting out hits like “Pleasant Valley Sunday,” “Daydream Believer,” and “Listen to the Band.”

He died of heart failure at his California home on Dec. 10, just 26 days after the last notes of “I’m a Believer” rang through the Greek and Nesmith walked offstage alongside Micky Dolenz, now the only surviving member of the Monkees. “I found out a couple days ago that he was going into hospice,” Dolenz told me just hours after he heard the news. “I knew what that meant. I had my moment then and I let go. It’s just good to know that he passed peacefully.”

“Peaceful” was not a word you’d have often used to describe Michael Nesmith’s demeanor over the decades, but something changed in those last few months. A Zen-like calmness took over as his body started to fail, and the prefabricated band that often seemed like the product of a Faustian bargain became a source of deep meaning to him. It was not the first time he’d surprised me over the years. Monkees are strange people, indeed.

Nesmith, Dolenz, and Tork onstage in 2012

Noel Vasquez/Getty Images

My first contact with Mike Nesmith came in early 2012, when I was reporting an obituary for fellow Monkee Davy Jones. I knew only the broad outline of Nesmith’s story. I knew he was heir to a substantial fortune that his mother, Liquid Paper inventor Bette Nesmith Graham, left him upon her death in 1980. I knew he played a pivotal though underappreciated role in the development of country rock in the early Seventies, thanks to three albums he made with his post-Monkees outfit the First National Band. I knew of his 1977 “Rio” video, the success of which inspired him to start a TV show called PopClips, which directly led to MTV (though Nesmith rebuffed the company’s offers to help run the network).

Most of all, I knew him as the Reluctant Monkee, the dour one who spent the entire Monkees chapter of his life in a simmering rage. The band was created in 1965 by TV producers Bob Rafelson and Bert Schneider. Almost instantly, their TV show and songs became wildly popular, but in the beginning they had almost no control over their music. This did not sit well with Nesmith.

I’d seen the 2000 VH1 movie Daydream Believers, where the Nesmith character punched a hole through a wall at the Beverly Hills Hotel when he was told by Monkees producer Don Kirshner he had no choice but to record the songs they gave him, even though he’d already penned classics like “Different Drum” and “Mary, Mary.” “That could have been your face!” biopic Nesmith snapped at Kirshner.

I knew he sat out every Monkees reunion tour with the exception of a 30th-anniversary run in 1997, when he bolted after just 11 shows, all overseas. When I saw the Monkees at a rib cook-off in the parking lot of a Cleveland airport in the summer of 2001, they didn’t mention Nez a single time from the stage, even though they played several of his songs. “He’s always been this aloof, inaccessible person,” Davy Jones said in 1997, “the fourth part of the jigsaw puzzle that never fit.”

My mental image of Nesmith at that point was a combination of Charles Foster Kane, Howard Hughes, and Gram Parsons. I imagined him wandering about his mansion, still muttering to himself about Don Kirshner and punching through walls whenever “I’m a Believer” came on the radio.

In the aftermath of Jones’ death, Dolenz and fellow Monkee Peter Tork readily got on the phone and spoke movingly about their late bandmate. I figured Nesmith was a long shot to talk, but I tracked down his lawyer and put in an interview request. Much to my surprise, Nez agreed to an email interview. And when the answers came back a couple days later, I was surprised at the eloquence and detail of his responses.

“For me, David was the Monkees,” Nesmith wrote. “They were his band. We were his side men. He was the focal point of the romance, the lovely boy, innocent and approachable. Micky was his Bob Hope. In those two — like Hope and Crosby — was the heartbeat of the show.”

“[Jones] told great jokes,” he continued. “Very nicely developed sense of the absurd — Pythonesque — actually, Beyond the Fringe — but you get my point. We would rush to each other anytime we heard a new joke and tell it to each other and laugh like crazy. David had a wonderful laugh, infectious. He would double up, crouching over his knees, and laugh till he ran out of breath. Whether he told the joke or not. We both did.”

This didn’t seem much like the bitter, resentful Michael Nesmith I had created in my mind. It felt like a man who missed his bandmate and was finally able to look back at his past with no small degree of joy. This was confirmed later that year, when Nesmith agreed to reunite with Tork and Dolenz for a brief American tour. “I never really left,” he told me. “It is a part of my youth that is always active in my thoughts and part of my overall work as an artist.… We did some good work together, and I am always interested in the right time and the right place to reconnect and play.”

The Monkees’ show at the Beacon Theatre on Dec. 2, 2012, left me stunned. The band had maintained a hardcore following over the decades that flocked to all of their partial reunion shows, but with Nez back in the fold, we were witnessing something extraordinary. It felt almost like Peter Gabriel back in Genesis or Peter Green back in Fleetwood Mac, an impossible dream happening right before my eyes. They played their catalog in chronological order, and even during early songs like “Your Auntie Grizelda” and “Last Train to Clarksville,” tunes that might have once caused him to stick his fist through drywall, Nesmith was smiling and engaged.

When they got to latter-day classics like “Circle Sky” and “Listen to the Band,” songs they recorded after the Monkee rebellion in 1967 that gave them the freedom to write and record their own material, he radiated joy and energy.

For the first time I had ever seen — possibly for the first time ever — Nesmith looked like he loved being a Monkee without any reservations.

Over the next few months, I listened to little music that wasn’t written or recorded by Michael Nesmith, and I learned a lot more about his life. He grew up in Texas, the only child of a struggling single mother (Bette Nesmith Graham didn’t found the company that became Liquid Paper until 1958). He moved to Los Angeles in the early Sixties after leaving the Air Force. He worked as a “hootmaster” during Monday-night hootenannies at the Troubadour, and released a handful of unsuccessful songs under the name Michael Blessing.

In 1965, he responded to an ad looking for “Folk & Roll Musicians-Singers for acting role in new TV series” in the trades. This was the brainchild of two television producers who wanted to cash in on the success of the Beatles. Nesmith was cast alongside fellow folkie Peter Tork, British stage actor Davy Jones, and Fifties child star Micky Dolenz, best remembered for the show Circus Boy. They would play a fake group that would release real music.

The latter part intrigued Nesmith the most, but he quickly learned that pro songwriters like Neil Diamond, Carole King, Carole Bayer Sager, and Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart would write the vast majority of the songs, with studio pros handling the instrumentation. The actual Monkees were asked to do little besides sing. The arrangement led to enormous hits like “I’m a Believer” and “Last Train to Clarksville,” which dominated pop radio and, along with the TV show, turned the foursome into superstars. But Nez felt like a phony even though the producers placated him by including a couple of his songs on the early albums.

By early 1967, Nez led a successful revolt, and the group was given permission to write and record their own songs, leading to the brilliant album Headquarters. But their sales slipped drastically in 1968, when their TV show was canceled after just two seasons, and Tork quit the band. Latter-day albums like Instant Replay and The Monkees Present (both from 1969) were commercial disasters, but they gave Nez the opportunity to fuse country and rock together in bold new ways, an interest that went back to his childhood in Texas, where he had equal love for both genres.

The experiments continued after the dissolution of the Monkees, when Nez formed the First National Band and recorded three near-flawless country-rock albums in an incredible burst of creativity between 1970 and 1971. None of them rose higher on the album chart than 143, and he dissolved the group right before the Eagles took country rock mainstream. Nez was broke and despondent. He gave his 1972 solo LP the bitter title And the Hits Just Keep on Comin’.

First National Band, circa 1973

GAB Archive/Redferns/Getty Images

“I was agonized, Van Gogh–agonized, not to compare myself to him, but I wanted to cut something off,” he told me in 2018, “because I was like, ‘Why is this happening?’ The Eagles now have the biggest-selling album of all time, and mine is sitting in the closet of a closed record company?”

Finding Nez’s Seventies albums before the recent wave of reissues required a bit of hunting, and when I finally heard “Joanne,” “Grand Ennui,” and “Propinquity (I’ve Just Begun to Care)” I was amazed. It was like discovering this whole other musical universe I never knew existed. I must have watched the “Rio” video 100 times, but I still laughed every time he took off into the sky like a human airplane with three women strapped to his back.

In the Eighties, after inheriting his mother’s fortune, Nesmith invested in movies like Repo Man and Tapeheads, and launched projects like an NBC variety show, Michael Nesmith in Television Parts. When MTV began re-airing The Monkees episodes in 1986, creating an entirely new generation of fans, he declined the chance to take part in the reunion tour because he simply couldn’t break free from his many business commitments. As the years went by and Sixties ideas about “authenticity” no longer resonated, the Monkees slowly became cool, especially when bands like Weezer, REM, and Death Cab for Cutie started gushing about their influence.

Nez wasn’t around much to enjoy the revival. His public profile dimmed down to almost nothing in the Nineties as he devoted nearly all of his time to quiet business pursuits. That made his return to the band in 2012 all the more shocking.

We finally spoke on the phone in 2013, when the Monkees were on the verge of launching another tour. I told him I always pictured him as a crazy recluse, and he just laughed. “I’m not the least bit reclusive,” he said. “I love being with people, and I love society and I love civilization and all the accoutrements. I think we’re all here for each other.”

It was the start of a long period where I found myself talking to Nesmith every few months, and seeing him play solo and with the Monkees at every chance I had. He was game for whatever topic I had in mind, whether it was a detailed breakdown of Monkees songs he wrote, his nontraditional memoir Infinite Tuesday, his newly-unearthed 1973 live album, his fraught relationship with Tork, or his obsession with Vaporwave, a fringe musical genre I’d never even heard of until he explained it to me. (The average age of most enthusiasts is about 17.)

When he was in New York in 2016, we met up at the Loews Regency hotel. He’d just come back from Comic Con and excitedly showed me photos on his phone of Marvel fans in elaborate superhero costumes. We got into a long, philosophical argument about whether or not the Monkees were even a real band. To me, their origins didn’t matter, and they were as real as any group I loved. Nez felt differently.

“All three of us have our own ideas,” he said. “This being, ‘What is this thing? What have we got here? What’s required of us? Is this a band? Is this a television show?’ When you go back to the genesis of this thing, it is a television show because it has all those traditional beats. But something else was going on, and it struck a chord way out of proportion to the original swing of the hammer. You hit the gong and suddenly it’s huge.”

I was disappointed when he sat out the Monkees’ 50th-anniversary tour that year, leaving Tork and Dolenz to bang the gong as a duo. He agreed to come back for a 2018 tour with Dolenz after health issues sidelined Tork, who died in 2019, but had to leave shortly before the New York date for emergency quadruple-bypass surgery. I worried that would mark the end of his touring career, but when we caught up on the phone a few weeks later, he assured me all was well.

“I was using the words ‘heart attack’ for a while,” Nesmith told me in his first public statements after the surgery. “But I’m told now that I didn’t have one. It was congestive heart failure. It has taken me four weeks to climb out of it. If anybody ever comes up to you on the street and offers you [bypass surgery] for free, turn them down. It hurts.”

Nearly every farewell tour in rock history has been bullshit. They are usually cynical ploys to suck money out of fans that have grown tired of shelling out big bucks to hear the same tired hits played yet again. But when the Monkees said they were going to call it a career after their tour this year, I believed them. Half the band was dead, and Nez was pushing 80 and clearly ready to hang up the green wool hat forever. He was starting to look tired, and had seemingly developed an insatiable appetite for marijuana. It came up whenever we spoke.

I flew to Los Angeles in September to be a fly-on-the-wall during rehearsals, with the plan of checking in every few weeks for a feature on their last hurrah. But before I even boarded the plane, outrageous rumors about Nez kept filling my inbox from hardcore Monkees fans. They had noticed his alarming weight loss in a series of videos he posted on Facebook and that he appeared disoriented, confused, and incredibly stoned. A disreputable gossip site posted a series of anonymous blogs saying that Nesmith was the victim of elder abuse. I started seeing the hashtag #SaveMikeNesmith in Facebook comments by some of the more fevered fans. “[He] is being starved, horribly abused, and gaslighted on a daily basis,” read a typical comment

I dismissed everything I read as typical internet nonsense, but when I arrived at the studio space in Burbank, Nez was nowhere in sight and the band had yet to lay eyes on him. The tour launch in Spokane, Washington, was just days away, and manager Andrew Sandoval was handling Nesmith’s vocals parts and leading the band through the set. They ran through “Porpoise Song,” “Last Train to Clarksville,” and “Steppin’ Stone” for an audience of one, and Dolenz’s vocals were as sharp and pristine as ever, reminding me yet again he’s one of the most underappreciated singers in rock history. But I kept staring at the empty stool next to him.

“Nez is under a lot of pressure,” Sandoval told me later that morning in a makeshift office opposite the rehearsal hall. “He wants to do the tour, but a lot of people around him don’t want him to do the tour. There’s all this chitter-chatter online that’s very negative. It’s tough.”

I asked if they considered delaying the tour until Nez felt better and Covid was further in the rearview mirror. “I don’t know if there will be another time on the calendar to do this,” Sandoval said. “Time is going on, and the window is closing to do this.”

This all sounded a little ominous, and I was still trying to process it when Micky Dolenz poked his head in and asked me to join him for a drink in the lobby of his hotel.

The Monkees in 1967

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Dolenz is the only Monkee to participate in every single reunion project the band has undertaken. “I never resented being known as a Monkee,” he told me between sips of pinot grigio. “Your career is like a train that takes an enormous amount of inertia to get it going. When it finally gets going, some people try to stop the train. Those are the people that you see in concert and they go, ‘I’m not going to sing any of my old hits. I’m going to change my entire image.’ They try and stop the train. Very seldom does that happen. It’s virtually impossible, and you just piss the fans off.”

“I knew after the Monkees I wouldn’t be getting any great, juicy parts,” he continued. “And I wasn’t really that interested. I went over to England, where I wrote and directed shows for years. When I came back to the Monkees in 1986, I came back with bells on. I was like, ‘Oh, my God, the Monkees! I remember that!’”

The Monkees’ 1986 comeback tour was a huge success, but there were tough moments behind the scenes. They had to pay Rhino, which own the Monkees trademark, a significant sum to use the Monkees name whenever they played. “That drove Davy insane,” Dolenz says. “We had endless arguments about it. He’d go, ‘But we are the Monkees! We shouldn’t have to pay!’ I’d say, ‘But David, if you want to make a Batman movie, you just don’t go out and make a Batman movie and use the logo. You have to make a deal with DC Comics.’ He never quite got that.”

And even Dolenz had a hard time shaking his anger towards Monkees creators Schneider and Rafelson for sharing little of the windfall they made from the group, instead investing it in movies like Easy Rider and Five Easy Pieces, which turned them into Hollywood titans in the Seventies. “I count myself lucky I lived in England during that time,” said Dolenz. “If I had been living in L.A. and seeing Bob and Bert and all their fucking money, it would have driven me crazy.”

Before we could delve any further into Monkees history, tour manager Dan Mapp appeared at our table and told us Nez was in an upstairs room and wanted to see us. Dolenz had seen him only once since the pandemic started and was eager to tell him about rehearsals and minor changes they made to the show.

When we walked in, the room smelled strongly of weed and Nez was perched in a leather chair near the window, looking even slimmer than he did in the last Facebook video. He was wearing a black sweatshirt with a marijuana-leaf logo on the breast pocket. A mask dangled from one ear, and a margarita was in his hand. “I’m so drunk,” he told us. “Hold on.”

“God, it’s good to see you,” Dolenz beamed. “You look great. You lost some weight.”

“I’ve trimmed down,” Nez said. “And I’m fucked-up.”

The only other people in the room were Nez’s new assistant, Gretchen, and a young woman named Melodie Akers, who worked for Nez for the past few years. It was hard not to wonder about Akers’ exact role in his life, and the way she stroked his fingers made it seem like she was more than an employee.

Akers had a leather pouch full of marijuana gummies and tiny plastic bags of weed, but when Nesmith reached for it, she pulled it back. “You had an edible,” she said. “You’re in good shape … besides, [your son] Jonathan doesn’t like you stoned. If you could hold off until you see him, I think he’d appreciate that. He’ll be here soon with [his wife] Susan.”

“She recognizes me as a stupid old man,” Nez said. “But I’m not a stupid old man. Anything I come up with that looks like fun …” He stopped and moved onto a different thought. “I keep thinking about boats on the water,” he said. “I want to go to the Mediterranean for 10 days.”

Dolenz changed the topic to tour rehearsals. “The band is shit-hot,” he said. “They haven’t dropped a beat.”

Nesmith was pleased to hear this, but horrified to learn that longtime Monkees guitarist Wayne Avers was going to miss the first few weeks of the tour due to Covid-related anxiety. “Mick, can I help him?” he asked, looking absolutely devastated. “I have millions of dollars!” (Avers joined up with the tour later and was fine.)

Gretchen headed out to charge up Nez’s Tesla, and Nez mentioned he just bought Teslas for all of his children. But he still had a fortune in the bank, and he wasn’t sure what to do with it. “I look around and go, ‘How the fuck did I get here?” he told Dolenz. “Who was so good, so generous to me in my life that I made it? There are people out there that are cold and hungry. I don’t know what I can do to help them.”

Jonathan and Susan arrived and warmly greeted “Pops.” (The Nez conspiracy theorists said he hadn’t been allowed to see his children, but this was obviously ridiculous. His other son, Christian, also plays guitar in the Monkees touring band.)

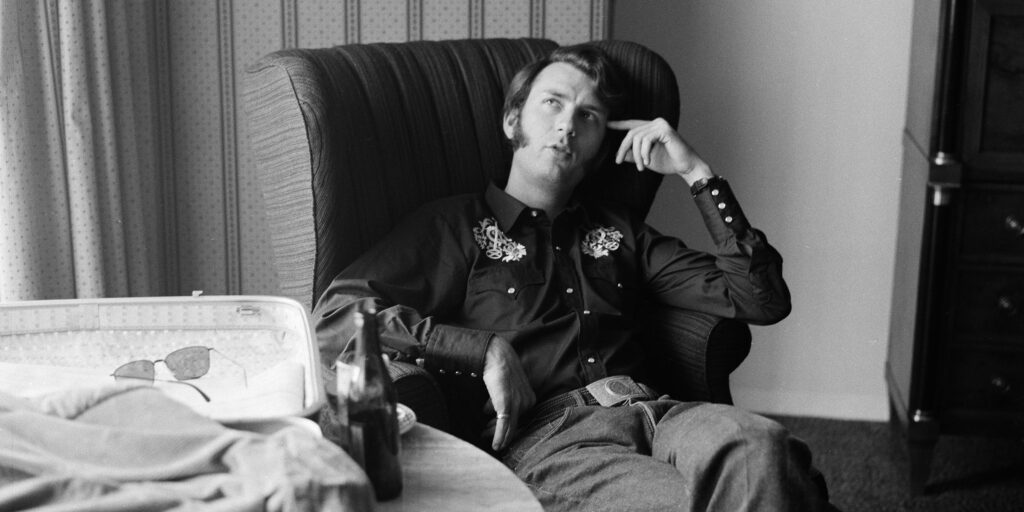

Nesmith in the Sixties

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

For the next two hours, I sat still on the couch, and soaked up the scene. The conversation went from the possibility of an official Monkees biopic or documentary to Dolenz’s love for revenge movies like Taken and Nobody to John Wayne films Nez has been watching on TCM. There was the sort of effortless rapport between Nez and Dolenz that only old friends can enjoy, and when they joked around it felt like missing scenes from the Monkees TV show.

“I just took Aaron Franklin’s MasterClass,” said Dolenz. “I’ve become a gourmet chef. My speciality is …”

“Roadkill,” deadpanned Nez.

“It’s tough getting a good roadkill dinner,” said Dolenz. “You have to chase that shit down. But if you get a good roadkill groundhog with a little béarnaise sauce …”

“And you add a little white wine to it,” said Nez.

They started giggling, and I thought how amazing it was that two men brought together by television producers in 1965 were still choosing to spend their free time together, and how much they seemed to genuinely love each other.

At rehearsal the next day, Nez was perched on a stool and learning how to interact with a teleprompter brought in for this tour. He offered Dolenz some weed. “No thanks,” he said. “I’m still high from 1967.”

The band launched into “Randy Scouse Git,” with Dolenz banging out the familiar intro on the kettledrum, but Nez just sat on his stool and stared at the ground. He looked deflated. Akers sat near him on a chair, looking concerned. “I’m going to go out back,” he said when the song wrapped. “And smoke some dope.”

He came back and they kicked into “Circle Sky.” Nez sang it with surprising force, but it seemed to take a lot out of him. He picked up a guitar for “Papa Gene’s Blues,” but playing and singing at the same time was clearly a challenge, and his vocals suffered. They tried it again without the guitar, and he’d remain guitar-less for the rest of the tour.

I headed to the airport the next morning worried about Nez, thinking a 10-week tour was way too much for him. And the reaction from the press and fans to the early shows was indeed negative, with a heavy focus on Nez’s diminished state.

“I gave him the out many times,” Sandoval told me several weeks later. “I said to him, ‘Should I cancel the tour? What do you think?’ He said, ‘No. I really want to do it.’ I felt we should go and do as much as we could since it was giving him a reason to kind of carry on. I felt in my soul this tour would be good for him.”

I asked Sandoval what exactly was ailing Nesmith. “Everyone is very protective of him, so nobody really wanted him to leave his house during the pandemic,” he said. “His means are great enough that he can have people bring him whatever. He sat and didn’t do much for a year and a half.… His muscles just atrophied and he got really weak.”

I brought up the conspiracy theories circulating online. “The fans want attention, specifically the fans that are the propagators of this stuff,” he said. “I feel like they are trying to shame us into telling them more about what’s going on than I feel they should know. Everything they’re saying is untrue. But if you get down in the mud with them, and you get nowhere, you just get dirty.”

“What they write hurts my heart,” he continued. “Their gripe is with one person, and it’s not Nez.”

He was talking about Akers, and I asked how Nez first came into contact with her. “They met about three years ago,” he said. “She got involved in some fan chat groups and made his acquaintance and then started working for him directly. She has worked in the past as his personal assistant, but she’s not actually an employee of the tour.”

I asked if they were dating. “I don’t understand the level of their relationship,” he said. “That’s an honest answer. They’ve never revealed anything specific to me about that.” (Akers declined to be interviewed for this story. It should be noted that the portrayal of her by some fans bears no resemblance to the compassionate caretaker I had the chance to meet. I found no truth whatsoever to the ugly rumors online.)

On Oct. 24, I went to Town Hall to see the band’s final New York City show. I held my breath when the lights dimmed, but Nez walked onto the stage with a huge smile on his face, his body no longer hunched over. He had a stool, but he opted to stand the entire night. The show was incredible, even if he lost track of the lyrics a few times and Dolenz had to jump in and save him.

Dolenz and Nesmith during the final Monkees show, at L.A.’s Greek Theatre, on Nov. 14

Scott Dudelson/Getty Images

Sandoval told me he noticed a shift with Nez when the tour hit Texas. “We were sitting outside at Stubbs BBQ,” he said. “Nez was telling stories at this table, and I looked at him and saw this light in his eyes, and it was like seeing my friend again. There was a really beautiful moment for me of going, ‘OK, this tour was a big, big gamble, but it’s paying off. He’s back.’”

Before the Huntington show on Oct. 28, I was escorted onto Nez’s bus. It was our first formal interview on the tour, and I knew I was going to have to bring up some uncomfortable questions. But first I wanted to ask about his feelings regarding the Monkees catalog. As recently as 2019, he was still dismissing it as “television music” and said he felt like he was “singing ‘Happy Birthday’ over and over” at Monkees concerts. I had the sense he no longer felt that way.

“People unjustly kicked us in the nuts over and over because they thought of it as vapid or whatever word you want to use there to indicate no artistic return,” he said. “But it is not. The more I sing it, the more I play it, the more I realize that even though the lyrics are pedestrian …”

He stopped himself and tried to gather his thoughts, knowing this is important. “I started off listening to my great aunt’s record collection,” he says. “One record she has was the Mills Brothers’ ‘Till Then.’ The lyrics go ‘Someday I know I’ll be back again/Please wait till then.’ It recently dawned on me that it was ‘Last Train to Clarksville:’ ‘And I don’t know if I’m ever coming home …’”

Tears filled his eyes as he recited the lyrics to the first Monkees single. “When I start to sing it, I get deep with emotion and all choked up,” he says, his voice cracking. “I think, ‘Wait a minute? Are we singing the same song?’”

I pointed out the Boyce-and-Hart-penned song is deceptively profound since it’s about a man headed off to war that thinks he’ll never see his love again. “That was missed with the Kirshner-ites,” he said. “They tried to kill those songs, and not for any other reason than they wanted the territory.”

I said Kirshner had no idea how willful Nesmith was when he first encountered him. “The corporate mentality that was at Screen Gems and Columbia, lumping both of those entities together, was the stuff of legend,” he said. “I didn’t know what to do with it.… And they wanted me to do anything but country music. That was hard.”

We shift into the farewell tour, and whether it means he’ll no longer be a Monkees when it ends. “I’m never going to quit the Monkees, no more than Paul McCartney will quit the Beatles,” he said. “It’s just not in the cards.” When he got the job five decades earlier, he presumed it would last no more than a few months. “Eventually I realized this was a point on the forever timeline,” he said. “And that’s not a burden to me at all. It’s been a dream job.”

By this point, any lingering doubts I had that he was in a state of mental decline were gone. This was the same Nez I spoke with nearly a decade ago. He was just a lot skinnier and a little more stoned. But I was still worried about his health, especially when he told me that, as a practicing Christian Scientist from birth, he didn’t believe in doctors. I pointed out that he seemed to believe in doctors back in 2018 when he had the quadruple-bypass surgery, which saved his life.

“That was because my loved ones and children were terribly frightened,” he said. “They went, [loud, whiny voice] ‘If you don’t get this operation, you’ll die.’ Well, that’s pretty draconian. I thought, ‘If nothing else, I’ll do this for them.’ But the idea that I was suddenly employing materia medica in a pristine field of clear metaphysics … was jarring. I got up to leave a couple of times, and they pushed me back down into the bed. My cardiologist was really good, though. I offered to get him high.”

I asked if he tought much about Davy Jones and Peter Tork these days, and he took the question in an oddly mystical direction. “I don’t really process that,” he said. “I just leave it to God to process. I have a very strong sense of a universal divine order. When that takes me over, life is heaven on Earth.”

He told me he wanted to start growing his own weed when the tour wrapped. He also told me people needed to stop fixating on his health. “The only thing that shows up is the occasional headache, the occasional stomach flu, the occasional foot rash,” he said. “I have a gorilla-level team of people who take care of me and this significant wealth that my mother left me … and right now, I’m happier than I’ve ever been, except when I was married to Victoria Kennedy.” (Nez dated Kennedy, a model 26 years his junior, throughout the Nineties, marrying her in 1999. She left him 2010. In Infinite Tuesday, he wrote that the divorce left him emotionally shattered.)

This seemed to be as good a time as any to bring up the ridiculous rumors he’s been subjected to elder abuse. “I am aware of this,” he said. “And I’m aghast. I want to be like, ‘What the fuck are you people doing? I’m a human being. You can’t just throw darts at me.’ And it’s all based in a fundamental non-truth. I’m sitting here. I’m fine! Please tell people that!”

Nesmith and Victoria Kennedy in 1993

Ron Galella, Ltd./Ron Galella Collection/Getty Images

I told him that many of the lies revolve around Akers. “Let me see if I can parse this so it doesn’t hurt her,” he said. “She’s in blind panic a lot of the time, and when she talks to fans they push her into that. They then think she’s got Nez tied down and she’s feeding him poison. How did that get started? It’s never been true.”

“Nobody is holding me captive,” he said. “I do exactly what I want to do, especially with my financial condition and everything else. I am the classic example of a guy that made it. I have nothing to complain about. Nothing at all.”

Onstage hours later, Nez introduceds the ultra-obscure 1969 Monkees song “While I Cry.” It had never been played live until this tour.

“There were moments in all of our lives where we went down to the basement … and we began to commune with these [Monkees] songs in a way I don’t think anybody knew,” he told the hushed crowd. “I thought, I need to write something that can express what’s going on in that lonely room playing those Monkees records by yourself…. So I wrote this song just to try and get at that moment you’re at as a young kid thinking about things that are just imponderable.”

What followed was one of the most intense moments I’ve ever witnessed in a concert. It was Nez, weeks away from his death, reflecting on the profound impact the Monkees had on their fans, something he only started to understand recently. Real tears filled his eyes when he got to the end of the song.

Thoughts keep turning round in my mind

Now I see reason and rhyme.

Time spent with you has brought me something

And I’ve lost nothing

If you are that kind.

They told me what you’d do

If I ever stayed with you

And sure enough,

It’s all come true.

The Monkees saga started long before I was born, and it lasted through the cancellation of their television show, the alienation of their fan base with the 1968 psychedelic movie Head, an army of critics that dismissed them as meaningless pop for children, and even the deaths of Davy Jones and Peter Tork, as well as Nez’s brush with death before his quadruple bypass. It didn’t feel like it could ever end.

When Nez’s team called me the morning of Dec. 10 to say that he’d died, I was shocked. Then my mind went to a lot of places. I thought of him using every ounce of energy he had left in him to play 40 final Monkees shows, honoring a body of work he spent decades running from. I thought of him tearing up while reciting the lyrics to “Last Train to Clarksville” on the bus, finally seeing the beauty in the bubblegum. I thought of the fact that whatever health matters he was dealing with at the end, he had every right not to share them with the public. And I thought of the moment he grabbed my arm right before I left his hotel room back in September.

“Do you think this is the end of an era?” he said, staring me right in the eyes. “It feels that way to me. It’s certainly the end of the Monkees. That’s a big deal.”