Madvillain Exec Egon Remembers MF DOOM: ‘He Was Such a Master of His Craft’

Eothen “Egon” Alapatt was out on a bike ride in Big Sur, California on New Year’s Eve when the news broke that Daniel Dumile, the rapper who performed as MF DOOM, had died two months earlier. Dumile’s death set off shock waves in the music community; but for Alapatt, who put together one of Dumile’s most celebrated and critically acclaimed projects — the 2004 collaboration with beloved, equally elusive hip-hop producer Madlib known as Madvillain — the loss was personal.

“My phone just exploded and I started going through it and I was like, ‘What in the fuck is going on?’,” Alapatt tells Rolling Stone. “It wasn’t until I saw Madlib’s text that I was like, I can’t believe this shit.”

Madvillainy was the only album DOOM and Madlib worked on together; a heady amalgam of leftfield, blunt-inspired beats and insanely intricate wordplay and concepts that remains, 17 years later, some of the best work either musician has ever recorded. Rolling Stone called the album “one of underground hip-hop’s greatest moments” when placing it on the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list.

“When we were making these songs, we thought we were making them for ourselves,” Alapatt, who met Dumile in 2002 as the general manager and A&R for Stones Throw Records, says. “We didn’t think anybody was going to care about them.”

Many people cared. Egon, who now runs the labels Now-Again Records and Madlib Invazion, spoke to Rolling Stone about the brilliant, but complicated, personality of DOOM, his innate creativity, and that time he officiated Egon’s entire wedding ceremony, in a mask, unscripted.

Obviously, I’m a huge 3rd Bass fan; I loved everything that they did collectively and as solo artists. Even as a child, I remember being heartbroken when I read that [DOOM’s brother and member of influential hip-hop group KMD] Subroc had been killed. I must have been 13. When Subroc died and KMD disappeared, none of us really thought too much about it; just like a casualty of that era of the music business. But when DOOM popped up again with those Fondle ‘Em records like “Hey!,” my mind was blown.

Fast forward a couple of years and I moved to Los Angeles and I’m running Stones Throw and working very closely with Madlib. We were all living together at the time and I had to bring Madlib down to the Long Beach Aquarium for an interview, where he told a journalist that he wanted to work with DOOM and J Dilla.

I had a friend who lived in the same part of Georgia as DOOM and I called him and said, “Would you bring a request to DOOM like, does he know who Madlib is? Does he know what Stones Throw is? Would he consider collaborating with Madlib? Just deliver him some records?” He brought Madlib’s records to DOOM’s house and just made the pitch and DOOM gave me a shout. DOOM had never heard of Stones Throw or Madlib. [Laughs] But he really liked [Madlib projects] Quasimoto and Yesterday’s New Quintet and he couldn’t believe it was all the same guy doing it.

“We would sit there looking at his lyrics and the way that he thought about how he was going to choose one word over another.”

When I was negotiating with DOOM to have him come out to L.A., it was super simple. It was just bare bones; not sure what might happen, but if it does happen, maybe it’ll be an EP. It’s going to have to be a minimum of $1,500 and flights and hotels. There was a literal bomb shelter in the house we all lived in and that’s where Madlib’s studio went. I remember when DOOM came in, because he didn’t look like the guy from KMD. He did not look like Zev Love X. He just looked different.

We were all just very chummy trying to figure things out. It wasn’t like he was telling me, “You can’t take a photo.” He would just put his hand up in front of his face and I was very respectful of that, of course. I remember him being in the basement, listening to music with Madlib and [Stones Throw founder] Chris [Manak a.k.a. Peanut Butter Wolf]. [DOOM’s business manager] Miranda [Jane] came up to my bedroom, which was also my office, and negotiated the terms of how they would collaborate together and how the money would be paid out. My main thought during that whole experience was, “Do whatever you need to do to get an album to happen.” I knew, even at that point, that an EP wasn’t going to be what this collaboration needed.

Chris wrote some crazy 24 Hour Party People-type contract on the back of a paper plate or something like that. You cannot just write the name of the project on a check and have that be anything other than a check given to a person. [Laughs] DOOM’s lawyer ended up framing that thing, whatever it was, and told me, “It’s the craziest thing I’ve ever seen.”

A lot of the first portions [of Madvillainy] were very simple. They were all done in our house between Chris’s bedroom, where he had a microphone, and Madlib’s Bomb Shelter studio. This was the one time that I was aware of, when Madlib was in the same physical space as his collaborator. For the most part, he didn’t work like that. After 2000, he stopped going into studios and working with rappers. The second portion was DOOM going back to Georgia and recording stuff and sending it our way. Then DOOM came back to L.A. and recorded some vocals and multiple takes on certain songs. It got to a point where we were recording songs and rerecording songs and getting songs ready to press, and we would end up with songs that didn’t end up with the vocal performance that he wanted.

After we met DOOM, Madlib and I went down to Brazil, in October 2002, with that first set of music, and the original version [of the album] leaked. So there was a lot of scrambling being done. The album had to be put into a new context. It was really chaotic. Madvillainy was not the priority at Stones Throw. Champion Sound [the collaborative album between J Dilla and Madlib] was the priority. Madvillainy was the project like, if it gets finished, it gets finished. We had to get the record done and out. And eventually we decided, this is the record. It took a lot of arguing back and forth as to what should be on the record, who should be on the record, if it should only be DOOM and Madlib, etc.

I made hundreds of records at Stones Throw and I was involved in each and every single one of them. But Madvillainy was the record that I was able to do. I forget what my credit says on the record; It’s something stupid because no one really thought about credit back then. “Project coordination.” It sounds like I got coffee for them. [Laughs] It was my baby. This was the record I believed in, so I fought every fucking step of the way for everything I believed in.

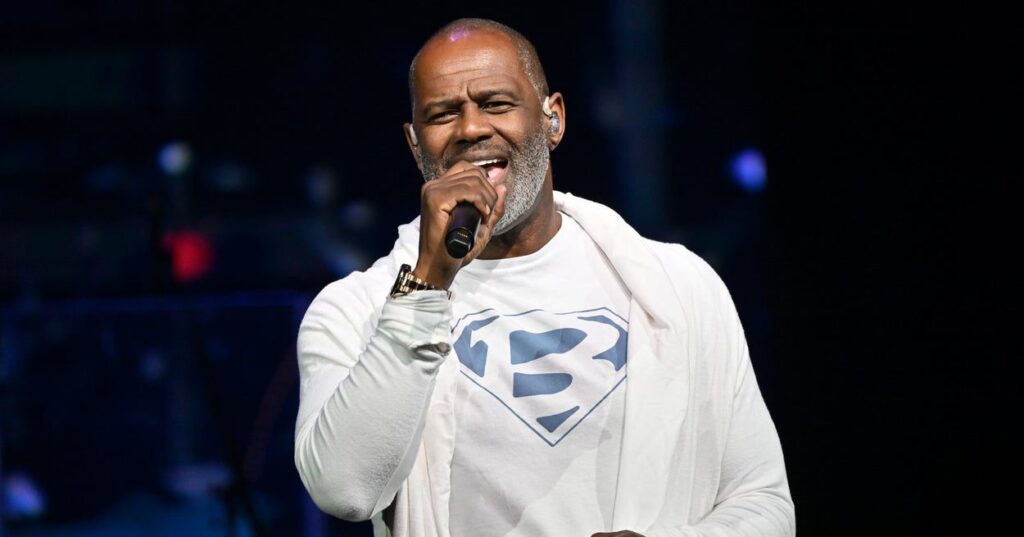

MF DOOM officiating Egon’s wedding in 2009.

Grace Oh

When I listened to the record [for the first time], my mind was blown because it’s the first time that something that I truly believe in had come together. And Madlib himself is rapping on it, something he told me he was never going to do again. It was like a dream come true to me. When we were making these songs, we thought we were making them for ourselves. We didn’t think anybody was going to care about them. It was either going to do really well or just be some other thing and we’ll move on to the next thing. But this was the thing that I came out here to do.

Dissecting DOOM’s lyrics is difficult. Let’s just go back to the most simplistic days in the early 1970s where you had radio DJs like Bill “Butter Ball” Crane or you had Blowfly rapping on a record – they’re basically talking with a great cadence and simplistic rhymes over a funk rhythm. Then you got the disco rappers and it’s the same standard type of hip-hop for years – until you get people like Rakim and Kool Keith. Then you hear Pharoahe Monch, who’s way more visceral in his imagery. By the time you got to Lord Finesse and Big L and people doing compounds and punchlines, but who are still witty and lighthearted, they were so far advanced that they didn’t even sound like they were creating the same music as those that came before them.

But by the time you got to DOOM, shit, you couldn’t hold a candle to him. I remember when he was recording “America’s Most Blunted” and he said, “Someday pray that he will grow a farm barn full / Recent research show it’s not so darn harmful.” This is some Shakespeare level shit. Like there’s no possible way I’m going to be able to explain this to people. I’d point that line specifically out to people and it would go over a lot of people’s heads. He did it so naturally that you didn’t realize how hard it was for him to do that over and over and over again. We would sit there looking at his lyrics and the way that he thought about how he was going to choose one word over another. It was transfixing being around a person that was such a master of his craft.

It became obvious to me, as I got a little bit older, that I was part of a long lineage of people who, like myself, are a bit anxious and weird and a little rough around the edges, but who could work with DOOM. It was this really lovely, familial bond that you could share with him that was also really complicated and difficult and full of pain and hurt. And that’s not just for me, but I’m sure for him, too. And there was a lot of that going on. And you had to be a really special sort to work with DOOM. It was just a really complicated thing working with DOOM and, at the same time, was one of the most rewarding experiences that one could have, because DOOM is one of the most special people that any of us working in music could ever possibly want to work with. He just thought about things in a different way.

I remember going through this with Dilla; within a month of his passing, people wanted to make him into an angel, but I remember him as a person. It was lovely, but I remember how complicated it was too. It doesn’t mean that the mourning is any less real. It doesn’t mean that his creativity is any less real. It doesn’t mean that the pain is any less real. How do you process that? Well, you tell the truth and after you tell the truth, you sit there with that being your experience, in the quiet times.

I really loved the guy, man. DOOM and I hadn’t spoken in years and I was immediately overcome with guilt and regret [when I heard about his death]. He and I would go through periods where we wouldn’t be on good terms. Anybody that was close with him went through a period — or multiple periods — where things were just haywire. And so the last communication I had with him was around when his son passed [in 2017] and it was a very simple exchange; just one of condolences. I just realized I was just angry; angry at myself and angry at DOOM. It’s because he’s a really special guy. And to spend time with that dude — like personal private time — was really hard to describe. DOOM was very talkative; he had a lot to say. He was super worldly and traveled and intellectual and spiritual — all these things going on at the same time. When you spent time with DOOM, if you knew him and he knew you, you really started to get to know how he viewed the universe. It didn’t take a month; It took years. But you got to know him and his philosophy.

He was a fucking really, really unbelievable person. When I called him up and said, “I’m getting married next month. Would you officiate our wedding? It would mean the world to us,” he said, “What’s the date?” He showed up at three in the morning, the morning before we were going to get married, and we walked through the whole thing. He had this big leather book and he walked everywhere with me, and he took notes. The next day, he showed up early and my mom asked him to put his mask on because she was like, “C’mon, that’s you.” He wore the mask through the whole ceremony and reception.

He did that not because he was getting paid; he never asked me for a dime. He showed up that night at three in the morning to make me feel comfortable, did the most beautiful job officiating, and then forgot that leather book. I found it as I was cleaning up, and I just wanted to see the notes he took about what I said to him, and when I opened that fucking book, it was just triangles, squares and circles. [Laughs] He freestyled the whole ceremony! I’m telling you this because, first of all, when I saw that, I burst out laughing — this guy is a genius. But also to say, he showed up and made me feel like I was the most important person in the world at that moment. How special is that? How many people can do that?