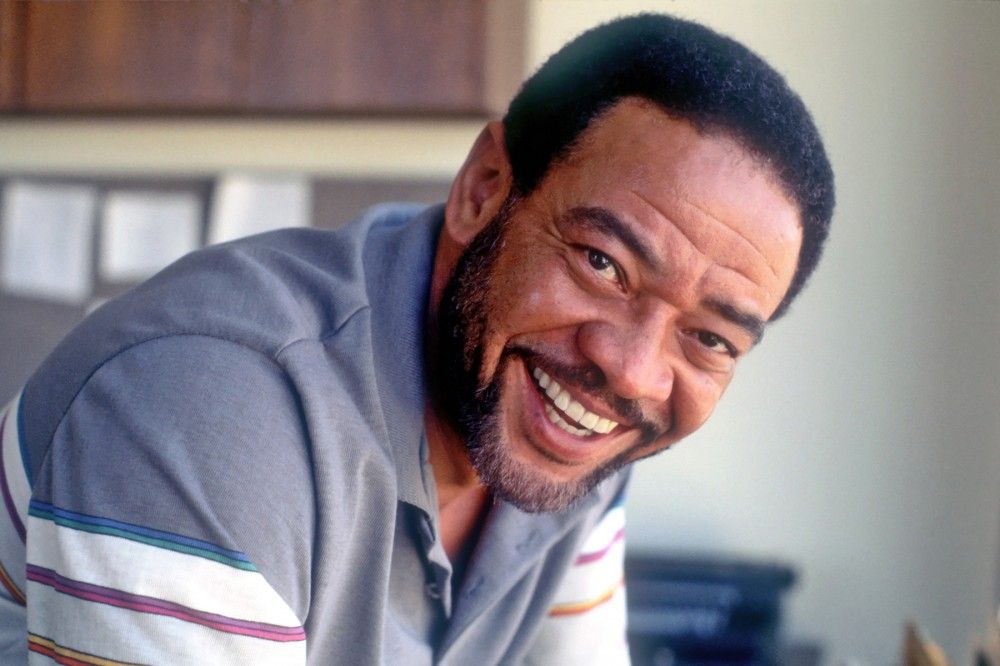

Kirk Douglas, 'Spartacus' Actor and Hollywood Icon, Dead at 103

Kirk Douglas, the epitome of old-school Hollywood star power whose intense performances conveyed his characters’ fiery and sometimes conflicted core, died Wednesday at the age of 103.

“It is with tremendous sadness that my brothers and I announce that Kirk Douglas left us today at the age of 103,” his son Michael said in a statement ( People). “To the world, he was a legend, an actor from the golden age of movies who lived well into his golden years, a humanitarian whose commitment to justice and the causes he believed in set a standard for all of us to aspire to. But to me and my brothers, Joel and Peter, he was simply Dad, to Catherine, a wonderful father-in-law, to his grandchildren and great-grandchild their loving grandfather, and to his wife, Anne, a wonderful husband.

“Kirk’s life was well lived, and he leaves a legacy in film that will endure for generations to come, and a history as a renowned philanthropist who worked to aid the public and bring peace to the planet,” Michael added. “Let me end with the words I told him on his last birthday and which will always remain true. Dad, I love you so much, and I am so proud to be your son.”

Three times nominated for the Best Actor Oscar, Douglas was one of American cinema’s finest tough guys; his muscular jaw and mischievous eyes able to suggest formidable men who might have dark secrets beneath their handsome surface. In movies as varied The Bad and the Beautiful, Spartacus, and Lust for Life, Douglas reveled in film acting’s sheer combustibility, delivering portrayals that were models of physicality and brute force. He was also among the first actors to segue into producing as a means to exert more creative control, helping to launch his son Michael’s career when he gave him the rights to the book-turned-play One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which earned a Best Picture Academy Award in 1975. “I never had any intentions of being a movie star,” Douglas said in 1957. “I never thought I was the type. My only aim was to become a stage actor…S]omeone had asked me to come to Hollywood, so I thought I’d take a chance.”

Born Issur Danielovitch in December 1916 to Jewish immigrants, Douglas grew up in upstate New York, dreaming of acting as an escape from a small-town community rife with anti-Semitism. “I wanted to be an actor ever since I was a kid in the second grade,” he recalled in his Nineties. “I did a play, and my mother made a black apron, and I played a shoemaker. And my father, who never interested himself in what I was doing, was in the back, and I didn’t know it. After the performance, he gave me my first Oscar: an ice cream cone. I’ve never forgotten that.”

Attending St. Lawrence University, Douglas would befriend fellow aspiring actor Karl Malden and then move on to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, where he met Lauren Bacall. His career was temporarily stalled by World War II — Douglas joined the Navy in 1941 after failing the Air Force’s psychological test — but was given a medical discharge in 1944. Upon returning to civilian life, Douglas snagged theater work, including the role of a soldier in 1945’s The Wind Is Ninety, which attracted the attention of film producer Hal B. Willis, who gave him a screen test and brought him to Hollywood. Indeed, Douglas’ first film role came in a Willis production, 1946’s The Strange Love of Martha Ivers.

Three years later, Douglas starred in Champion, about an amoral, ambitious boxer. The role landed him his first Academy Award nomination and cemented his persona as a bruising onscreen presence not to be taken lightly. The actor’s uncompromising demeanor was reflected offscreen as well: In 1955, he formed his own production company, Bryna Productions, named after his beloved mother. Douglas’ aim was to find material that spoke to his passions, rather than being at the mercy of others to determine his career destiny. “The impact of television brought enormous changes in the Hollywood studios, with fewer and fewer films being produced,” Douglas once recalled. “Many stars found themselves unemployed and I wasn’t about to let it happen to me.…It was a matter of survival. It still is.”

Douglas’ survival instincts translated into his performances during the 1950s. Whether playing an unscrupulous journalist in Billy Wilder’s acidic character portrait Ace in the Hole or a soulless producer in The Bad and the Beautiful (the latter netting him his second Oscar nomination), the actor brought unsettling amounts of intensity to characters whose moral rot shone all over their face. But he was just as eloquent playing the hero: His portrayal in Paths of Glory (1957) of a principled World War I French colonel defending the honor of three of his soldiers during a rigged court proceeding is a stunning display of righteous decency. (It also began a friendship with then-rising director Stanley Kubrick, whom Douglas would bring on board to helm 1960’s Spartacus.)

Kirk Douglas as Spartacus Photo: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Vincente Minnelli’s 1956 biopic of Vincent van Gogh, Lust for Life, became arguably his finest performance and certainly his most blistering. The film remains one of the most vivid portraits of artistry ever committed to screen, with Douglas pouring his soul out to play the troubled, brilliant painter, a role that would earn him his third Oscar nomination. “I don’t think I’d be much of an actor without vanity,” he confessed to biographer Tony Thomas. “I was terribly disappointed not to win an Oscar], especially for Lust for Life. I really thought I had a chance with that one.…However, I don’t want to appear ungrateful. I’ve been very lucky. Few people manage to do what they want in life. I have.”

Douglas continued to work steadily through the Sixties and Seventies, but his next great achievement might have been pursuing the rights to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Ken Kesey’s anti-authoritarian 1962 novel about a rebel instigating an uprising at a mental institution. Douglas turned the book into a Broadway play in which he was the star, but after years of frustration in which no Hollywood studio would consider adapting the work for the screen, he gave the rights to his son Michael. The eventual movie version, which starred Jack Nicholson, won five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Actor. In an ironic twist, Douglas’ son had an Academy Award before he did. (Kirk would eventually receive an Honorary Oscar in 1996.)

In his later years, Douglas easily transitioned to the role of revered elder statesman, playing lovable rascals in lightweight comedies like Tough Guys (1986) and Oscar (1991), the former being the sixth and final film in which he’d co-star with his good friend Burt Lancaster, whose drive to become a producer in the 1950s inspired Douglas’ own pursuit of the same aspiration. In 1996, shortly before accepting his Honorary Oscar, Douglas suffered a stroke that severely impaired his speaking ability. He wrote about the experience in his memoir My Stroke of Luck with candor and dark humor: “The doctor’s words echoed in my mind: It’s just a minor stroke. Yeah, minor to you, major to me.”

As Douglas got older, his reputation was further burnished retroactively for his willingness to stand up to the 1950s Hollywood blacklist, fighting to get disgraced screenwriters credits on his pictures — particularly Dalton Trumbo, who had written Spartacus. “I’m very proud that Spartacus broke the blacklist, because that was very important,” Douglas once said with pride. In 1991, he received the Writers Guild of America’s Robert Meltzer Award for his commitment to ending the blacklist, and in 2012, he wrote a book, I Am Spartacus!: Making a Film, Breaking the Blacklist, that highlighted his role in hiring Trumbo, an outspoken communist, for the swords-and-sandals epic. (That same year, journalists John Meroney and Sean Coons offered evidence arguing that Douglas overstated his importance in ending the Hollywood blacklist. Their contention was that the actor-producer wasn’t nearly as courageous as he claimed to be and that he actually threatened those who wouldn’t go along with his version of events.)

Nonetheless, Douglas leaves behind a legacy of indomitable performances and, more importantly, a bare-knuckle ruggedness rarely seen in today’s far tamer Hollywood. In a 1969 interview with Roger Ebert, Douglas proclaimed, “Being a star doesn’t really change you,” he said. “If you become a star, you don’t change — everybody else does. Personally, I keep forgetting I’m a star. And then people look at me and I’m reminded. But you just have to remember one thing: The best eventually go to the top. I think I’m in the best category, and I’ll stay at the top or I’ll do something else. I’m not for the bush leagues.”

Spartacus

Lust for Life

The Bad and the Beautiful