‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ Is Martin Scorsese’s Great American Tragedy

The Osage called it the “Reign of Terror.” Once upon a time, long after they’d been forcibly displaced and sold land in the Oklahoma territories deemed barren and unfruitful, the Indigenous tribe had discovered oil under the ground. And more oil. And still more oil after that. They became rich. Like Gatsby-level rich. Then, in the early 1920s, members of the community began suffering from a mysterious “wasting illness.” And when two Osage citizens were found within a day of each other in 1921, both with gunshot wounds to their heads, it became clear that someone was continuing an American tradition of genocide on a personal level.

An adaptation of David Grann’s 2017 true-crime bestseller, Killers of the Flower Moon would be a big deal regardless of who was making it. That this is the latest from Martin Scorsese, starring both Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert De Niro — acting together for the first time in one of the director’s movies — and the closest thing he’s made to a genuine Western, has caused it to be viewed less as a film than as a potential earthshaking event. A single still of DiCaprio and Lily Gladstone sitting at a table, her staring sideways at him as he blankly stares heavenward, was the only hint we had for months regarding what was in store; film nerds studied it like the Zapruder footage for clues. Anticipation mounted. Questions were abundant: Would it focus more on the community’s response to the killings, or the F.B.I.’s investigation? Was this going to be Scorsese’s corrective to a genre that’s done wrong to Native people for over a century? Or would it turn out to be another well-intentioned white savior story? What’s the deal with DiCaprio’s jaw?!

We now have answers, and can confirm that the end result was indeed worth the wait. Structured as the sort of throwback, big-picture epic that characterized ambitious moviemaking in the 1970s and early ’80s, Killers of the Flower Moon is, at its core, a love story. But it’’s also a mystery, albeit not one with simplistic whodunnit solutions; a highly gothic take on the white-hat horse operas of yesteryear; a star vehicle, featuring a career-best performance from an actor whose talent too often gets eclipsed by his celebrity; a continuation of a sui generis 50-year collaboration between two artists/coupla guys from Little Italy; and an indictment of white supremacy, then and now. Above all, it’s a Martin Scorsese picture, brimming with reverence for a culture that survived a horrible trauma as it is filled with exhilarating flourishes, film history references, and explorations of the faultline between the sacred and profane. And yes: It’s a masterpiece.

The word’s overused, sure. But what else can you call a work that finds the 80-year-old director — considered by many to be our greatest living American filmmaker and caretaker of the seventh art’s flame — turning a sprawling, three-and-a-half-hour drama involving power, corruption and our nation’s toxic past into an intimate story, without sacrificing its depth or scope? Opening on a surreal dance under a shower of “black gold” and old-timey silent newsreels of Oklahoma’s Osage aristocracy, the movie immediately establishes a final bastion of wild-frontier life mixing with financial prominence in the early ’20s. A stranger, new to this world of wealth and old, weird American types trying to grift it, pulls into town: This is Ernest Burkhart (DiCaprio), fresh off the frontlines of World War I. The young man in the doughboy uniform is, to blunt, not very bright. He does like whisky, women and money, however, and not in that order. And that makes him an attractive prospect for manipulation to one man in particular.

Burkhart has come to the Sooner State to work for his uncle, William Hale (De Niro), the cattle baron who considers himself the best friend the Osage have ever had. “‘Call me ‘King,’” the older man tells his nephew, and sits him down inside his den to explain how things work round these parts. A person shouldn’t drink too much, lest he indulge in “blackbird talk.” Be careful around the criminal elements who treat the surrounding areas as a way station between illegal activities. If he’s going to get into trouble, make it “big trouble.” He should consider Hale more of a father figure than an uncle. (Let’s pause for a moment to praise Jack Fisk, the legendary art director and production designer of Badlands, There Will Be Blood and too many other landmark movies to count; he and his team turn Hale’s ranch into a warped Xanadu that’s part mausoleum, part masculine predator’s lair. It’s one of many extraordinary, character-informing touches in a film filled with them.)

Most of all, Hale says, Ernest should get to know as much about the Osage as he can. “They are the most beautiful people in the world,” he says, before the movie abruptly cuts to a Native American having a violent seizure on a wooden apartment floor. A series of deaths, all of them involving healthy Osage locals who suddenly fall ill or fall victim to outright murder — and most of them accompanied by a voice saying “No investigation” — play out. Then we meet the woman narrating this homicide montage: Mollie Kyle (Gladstone). Her family owns one of the tribal land headrights that’s kept the money coming in to town. Ernest ends up becoming her driver, partially out of circumstance, and then her sweetheart, initially because his uncle thinks getting in good with the Kyles would benefit him.

Mollie has a sunbeam of a smile, which sometimes translates as the look of pity you’d give a slow child when Ernest says something ridiculous. She recognizes what this white man is after — “Coyote wants money” — but he’s handsome, and kind, and is honest about liking the good life and liking her. They fall in love and marry. Meanwhile, one of her sisters, Minnie (Jillion Dion), has been inexplicably sick. Her mother, Lizzie (Tantoo Cardinal), too, has seemed infirm as of late. Then her sister Anna (Cara Jade Meyers), the wild child of the family, goes out gallivanting one night and doesn’t come home. They eventually find her body near a creek. “This blanket has become a target on our back,” Mollie says. As for Hale, he keeps insinuating that Ernest get what’s rightfully his. And soon enough, this “Reign of Terror” that everyone in town is talking about soon begins to hit Mollie herself, much closer to home….

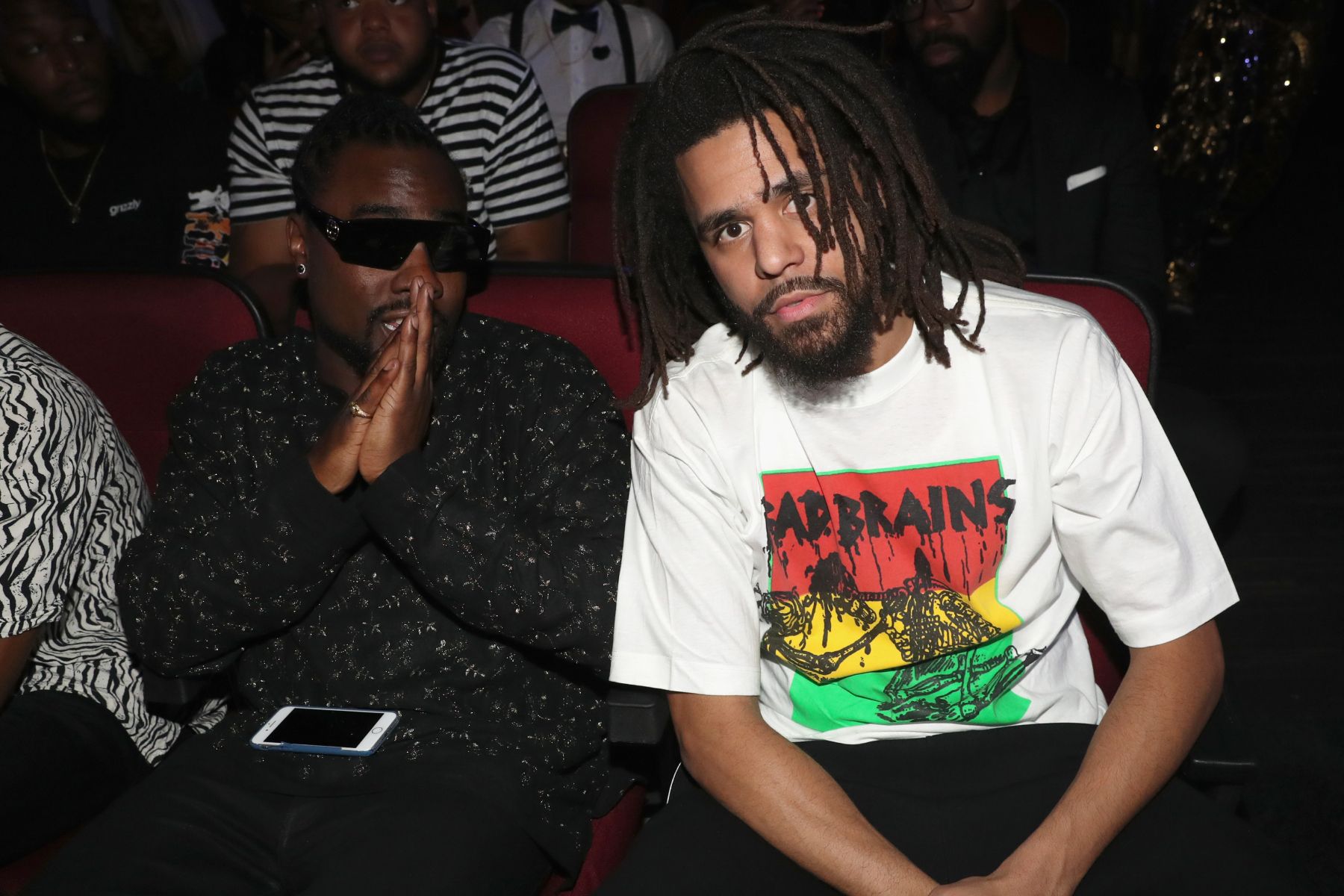

Robert De Niro and Leonardo DiCaprio in ‘Killers of the Flower Moon.’

Melinda Sue Gordon

It’s Ernest’s two central relationships — between a husband and his wife, and between a malleable man and the surrogate father who becomes a devil on his shoulder — that define not just Killers of the Flower Moon’s dynamic, but distinguish the movie from its source material. David Grann’s book ran parallel narratives, following both the timeline of these serial killings and the concurrent formation of a government-sanctioned “Bureau of Investigation” by J. Edgar Hoover; the Osage murders were one of the first major cases they took on, with a former Texas Ranger named Tom White chasing down leads. It was a detective story mixed with deep reportage on systematic racism that had been treated as a historical footnote. “When I began the story I was thinking, ‘It’s a whodunnit kind of thing, right?’” Grann noted upon the book’s publication. “And by the end, [it] was like, ‘Who didn’t do it?’”

Scorsese and his fellow screenwriter, Oscar winner Eric Roth (Forrest Gump, The Insider, Dune) take a different tact. Tom White, played with an impressive sense of quiet authority by Jesse Plemons, doesn’t show up until the last quarter of the movie. Instead, we spend a lot of time with Ernest and Mollie, and the tension that builds when it looks as if he’s slowly removing the one person standing between him and his wife’s wealth. It’s a stand-in for the larger betrayal that’s happening to the community, complicated by the fact that DiCaprio plays Ernest as someone devoted to his wife. The actor has always excelled in his work with Scorsese because he understands how to play duality, a recurring theme in the filmmaker’s back catalog overall (see: Catholicism). Here, DiCaprio is forced to psychologically crack open a murderer under the sway of a Svengali and in love with his victim. Not even a set of false teeth and a Southern-fried, slow-witted accent can derail how brilliantly he plays the conflict, the denial, the guilt that comes with double-crossing your soulmate. (DiCaprio and De Niro’s scenes together, it should be said, give you the impression of watching two pro boxers trading punches, and you bemoan the fact that it’s taken them this long to follow up on their This Boy’s Life rapport.)

That’s what Scorsese is interested in — a love story tainted by greed, collusion, and a society built on prejudice-scorched earth rather than a procedural — and that’s what DiCaprio and Gladstone give us. She’s the undisputed MVP of Killers, which is no easy feat when you’re up against two best-of-their-generation contenders. It’s hard to think of another working actor who knows how to use just the movement of their eyes to such good effect; a scene in which she sizes up DiCaprio before inviting him to silently contemplate a rainstorm next to her makes you think you’re seeing Dietrich one second, De Havilland the next. It helps that cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, another longtime Scorsese collaborator, knows exactly how to light her, but Gladstone is the one making the heavy lifting seem graceful. She turns Mollie into someone who doesn’t trust easily; who gives a man she knows to be good at heart her trust; and then watches it all turn to ash as he keeps giving her “medicine.” She gives this epic a broken-hearted pulse and its backbone.

Their doomed romance is also the throughline that guides Killers of the Flower Moon though a number of expository patches, cultural anthropology, bonus genre detours (black comedy, courtroom thriller, Freudian family drama), and a lot of covered historical and sociological ground. Scorsese is after big game here, and like The Irishman, this range noir writ large justifies its length. What sticks with you, though, is not the film’s hugeness but its humanity. It ends not on a moment of mournfulness and opts, instead, for a closing image that suggests survival, endurance, a ritual of affirmation. No one makes movies like this anymore, that go for broke yet keeps its eyes on the universal experiences of love, death, healing, and forgiveness. Maybe no one else can. But we’ve got a truly masterful example of how to do it, from an artist who hasn’t given up on the power of the moving pictures as mass-appeal empathy machines. Cinema’s not dead yet.