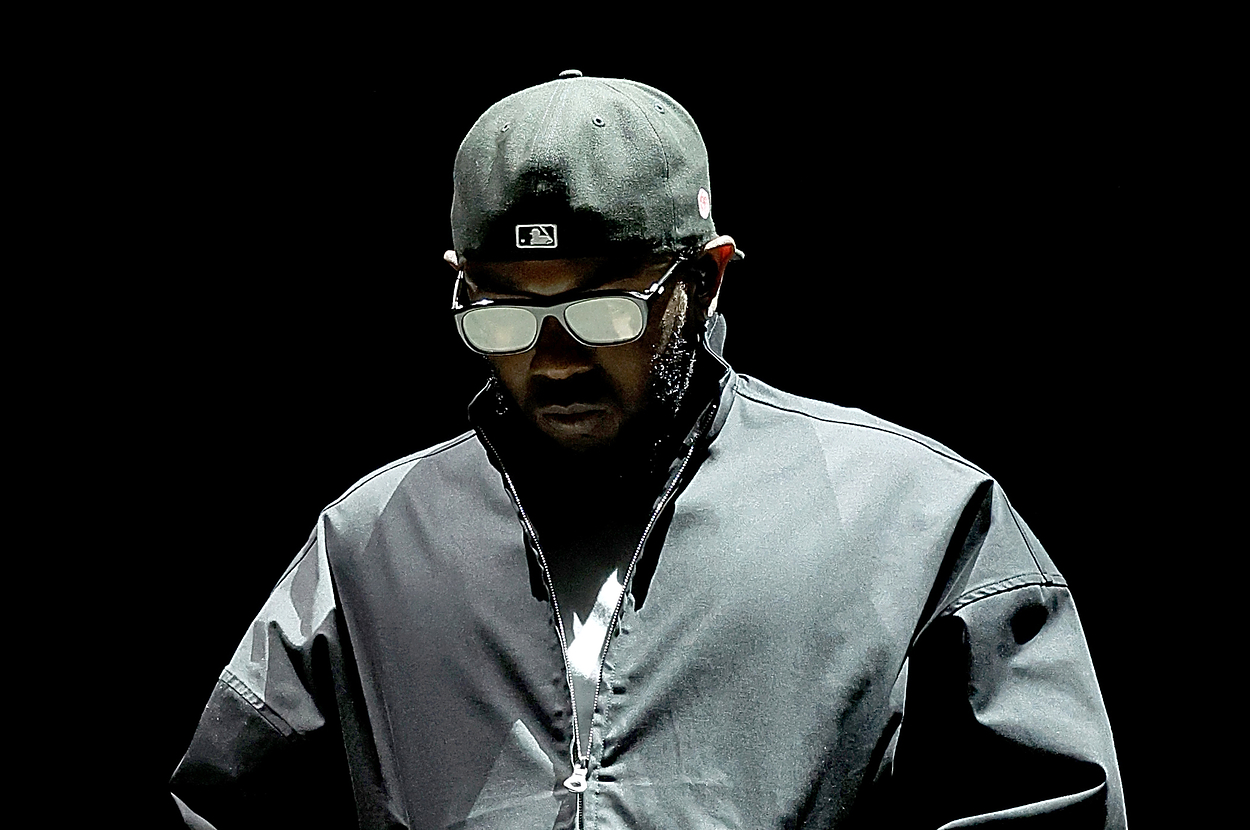

Kendrick Lamar’s “Euphoria” Is a Good Jab, Not a Knockout Punch

Compton rapper Kendrick Lamar doesn’t quite have that science figured out. There’s something clarifying about his flaws as an emcee when you see him struggle with a knockout punch like this song should be. Despite all of his lecturing and professorial intensity, Lamar doesn’t contain enough economical brevity or cocksure swagger to land a fatal blow on “Euphoria.” The six-minute diss track, released Tuesday morning, has uppercuts that do land. He raps with force, and the hate that he has for Drake is palpable. “I hate the way that you walk, the way that you talk, I hate the way that you dress,” he says, reminding us all that hating is a lost art in the world. A lot of his stabs at Drake are disrespectful and personal—at once point he calls Drake’s crew “OV-ho niggas”—but Kendrick’s flow, which can be disjointed and chaotic at times, holds him back from creating a song that is audacious but abridged.

In the first minute of the song, Kendrick uses his “PRIDE” flow, which sounds like he’s reading a children’s book, all drawn out and patient. Then he changes direction, using his theatrical voice to switch the tenor and atmosphere of the song. It’s quite like Kendrick in general—throwing density at you in an effort to overwhelm, putting all of his force out there. If that is compelling to you, then it works, and has worked for you throughout his career. But it doesn’t make for a spectacular diss track. “Euphoria” is closer to a less-charismatic version of “You Gotta Love It,” Cam’ron’s hilarious but entirely too lengthy diss towards Jay-Z, than it is to the intimidating mastery of “Story of Adidon” or “Hit Em Up.”

The insults are there, to be certain. Drake’s racial identity as a Black, Jewish Canadian is prevalent on the song, with Kendrick saying that he does not want to hear Drake saying “nigga” anymore in a melodic flow that sounds like a demonic lullaby. Disgruntlements like this are fair game to be rapped about on wax—Drake, the son of a Black musician from Memphis and Jewish florist from Toronto, has consistently made his complicated upbringing, compelling identity, and dubious relationship with Blackness a part of his music and story—but by the end of the song, it doesn’t feel like you just saw a great boxing performance.

“Euphoria” doesn’t have the showmanship; it doesn’t have the conceit—the negative and livewire expression—that you need. Where 2Pac said, “That’s why I fucked your bitch, you fat motherfucker,” Kendrick is saying, “I make music that electrify ’em, you make music that pacify ’em.” That underlines the main issue with this beef: these guys don’t have all that much to say to each other. It is not Biggie and Pac, who were competing over pride, women, violence, money. Jay-Z and Nas were trying to vie for the heart of New York. Jadakiss was tired of 50 Cent’s seemingly unmovable force. Drake is a pop star who can rap, a fan of hip-hop who can sing. Kendrick Lamar is a bare-knuckles poet, someone who I imagine raps without even hearing a beat. “Euphoria” is not whimsical, nor fanciful enough. It’s far messier, full of air punches, and sexless. It’s not rap as a wrestling performance, it’s rap as fan service for the types of people who view Drake as just a famous pop star, and not a model of eccentric Black pop.

Kendrick Lamar is not 2Pac, even if he’d like to be. He’s more in line with the Freestyle Fellowship crowd than Pac, who makes better use of negative space, gravitational songwriting, and unfiltered charisma. That’s abundantly clear here. The love of Pac is all around Kendrick—from his dislike of Drake buying the fallen rapper’s ring, to his ties with Los Angeles County, to his habit of calling himself a messiah—but the more he tries to go nuclear, the less he sounds like him.