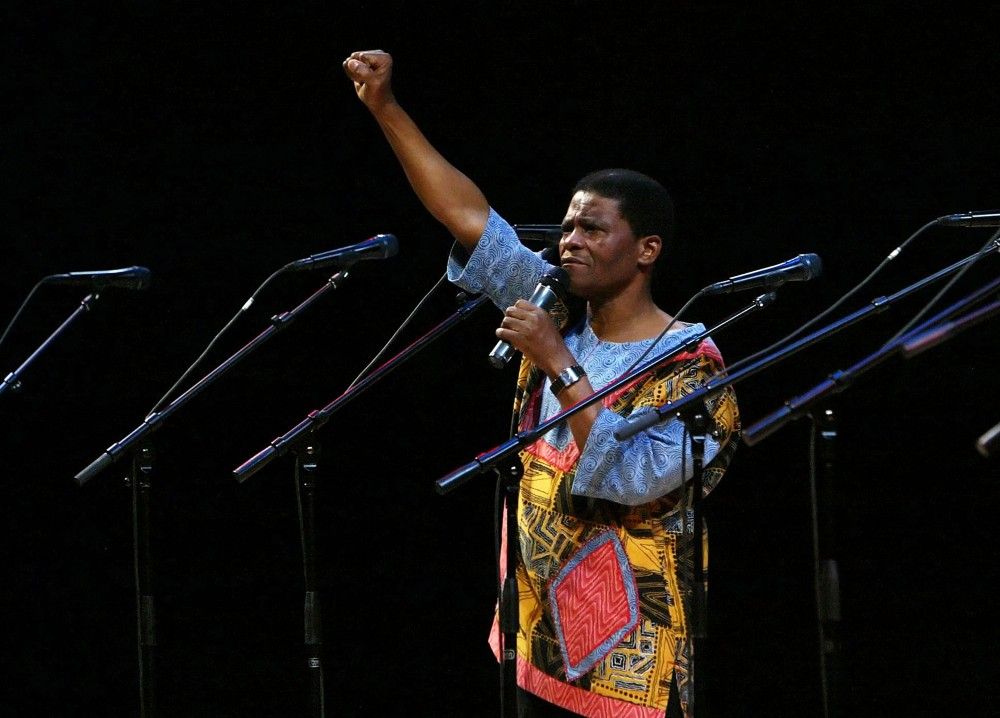

Joseph Shabalala, Ladysmith Black Mambazo Founder, Dead at 78

Joseph Shabalala, founder and director of the Grammy-winning South African vocal troupe , died Tuesday, the South Africa Times reports. He was 78.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s manager, Xolani Majozi, confirmed Shabalala’s death, saying the musician was with his wife when he died. Majozi said a statement from Shabalala’s family would be released Tuesday, but added, “The group Ladysmith Black Mambazo] is on tour in the U.S., but they have been informed and are devastated because the group is family.”

On Twitter, Ladysmith Black Mambazo wrote: “Our Founder, our Teacher and most importantly, our Father left us today for eternal peace. We celebrate and honor your kind heart and your extraordinary life. Through your music and the millions who you came in contact with, you shall live forever.”

Bhekizizwe Joseph Shabalala

Our Founder, our Teacher and most importantly, our Father left us today for eternal peace. We celebrate and honor your kind heart and your extraordinary life. Through your music and the millions who you came in contact with, you shall live forever. pic.twitter.com/2eDNFDUAGf— Ladysmith Black Mambazo (@therealmambazo) February 11, 2020

Founded in the early Sixties, Ladysmith Black Mambazo specialized in the traditional South African Zulu style of isicathamiya music and became world-renowned after appearing on ’s 1986 album, Graceland. Shabalala co-wrote two songs on that record — “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” and “Homeless” — and he and Ladysmith Black Mambazo also joined Simon on his sprawling tour in support of the LP.

Simon learned of the group after watching them on a British television special — where they sang a song in German, no less — and in a 1987 interview with Rolling Stone he called Shabalala “an enormous cultural treasure, a cultural gold mine.”

Shabalala was born August 28th, 1941, in Ladysmith, South Africa, and left home for the nearby town of Durban when he was a teenager. There, he found work in a cotton factory, but also began to sing with a local isicathamiya group called the Highlanders. When he returned to Ladysmith, he formed Ladysmith Black Mambazo with relatives and other townspeople. The group’s name paid homage to the members’ hometown, and “Black” referred to the oxen and honored Shabalala’s farming roots. “Mambazo” is the Zulu word for a chopping ax — an allusion to the group’s vocal prowess.

Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s breakthrough came in the early Seventies with the release of their debut single, “Unomathemba,” which resonated with both black and white audiences in apartheid South Africa. Their first album, Amabutho, arrived in 1973 and became the first record by black musicians to go gold (25,000 copies sold) in South Africa. A deluge of equally successful records would follow, and although the group’s profile rose, its roots remained humble. At one point, Shabalala had to corral all of Ladysmith Black Mambazo for a last-minute appearance on Dutch television, but because some of the members still didn’t have phones, he had to put out a “calling all Mambazos” notice on local radio.

Following their collaboration with Simon on Graceland, Simon returned the favor and produced Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s 1987 album, Shaka Zulu. The album earned the group their first Grammy Award, for Best Folk Recording, and they would go on to win four more statues: Best Traditional World Music Album in 2004 and 2009, for Raise Your Spirit Higher and Illembe, and Best World Music Album in 2013 and 2018, for Live: Singing for Peace Around the World and Shaka Zulu Revisited: 30th Anniversary Celebration.

Along with Simon, Ladysmith Black Mambazo collaborated with an array of other artists, including Stevie Wonder, Dolly Parton, Emmylou Harris, Melissa Etheridge, and Josh Groban. They also provided music for films such as The Lion King, Part II, Coming to America, and Invictus. A documentary about the group, On Tip Toe: Gentle Steps to Freedom, earned an Oscar nomination in 2001 for Best Documentary Short. Ladysmith Black Mambazo also supplied the music for the 1993 Broadway musical The Story of Jacob Zulu, which earned them a pair of Tony nominations and a Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Music in a Play.

Shabalala retired from Ladysmith Black Mambazo in 2014 due to deteriorating health. Although he continued to make sporadic appearances with the group, he passed on the leadership mantle to his son, Sibongiseni.

In a 1987 story for Rolling Stone, Shabalala explained how deeply ingrained music was for him, and continued to be, even as Ladysmith Black Mambazo became world-famous. “I am not in a hurry to go outside and sing for somebody,” he said. “There is something in me, in my veins, that needs music. That’s all. To me, it is good to sit down and sing.”