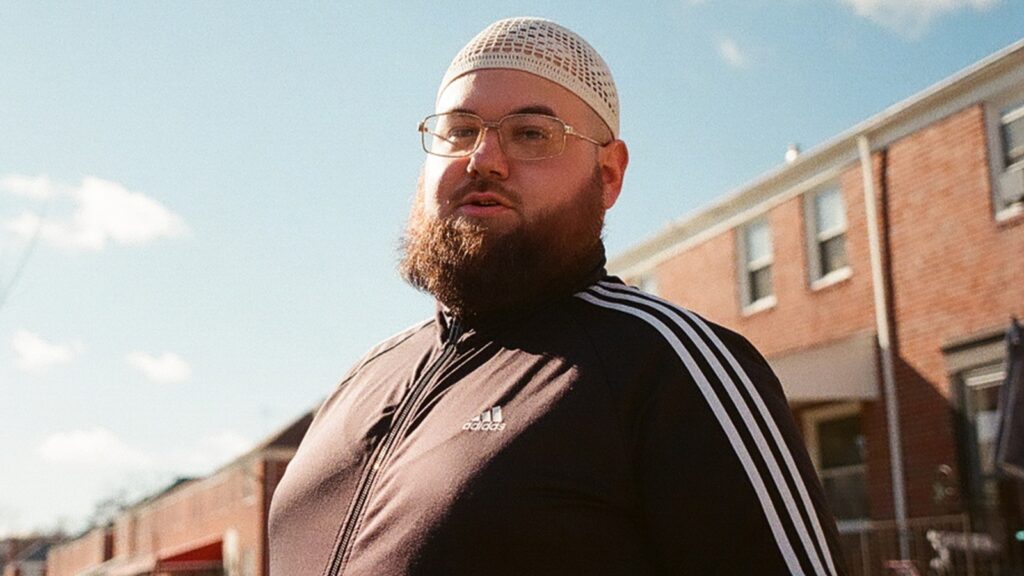

John Wells’ Nimble Raps Resurrect His Father

This is going to seem like an article about John Wells’ dad. It’s not, exactly, though the Baltimore rapper would probably be content if it was. While his recent album, The Apprehension of John Wells, is self-titled, it’s deeply indebted to his father, Richard Thomas Scible, known better as Rick or Ricky, who died on July 6, 2020, after a bout of drug and alcohol withdrawal evolved into kidney and liver failure. Though he had been receiving dialysis in the weeks before, once Scible’s insurance opted out of continued coverage for the treatment, Wells says, he soon passed away.

Wells’ Apprehension is stunning, originally released in December and followed by a deluxe version at the end of February. On the album’s penultimate track, “No Drugs in Heaven,” he raps for nearly seven minutes straight from the first-person perspective of his father. The song is a marvel, a feat of color and empathy following Scible from his birth on July 31, 1968 (“My mama said a tree had fell on the crib the same day,” Wells raps as his dad), to his death bed nearly 52 years later (“I was in the hospital in Miami, where they say the gangsters go to die”), to a final place of peace (“Regardless of the fact I had no money when I died/I’m the reason Lor Luckee the best rapper alive”).

Luckee is, as Wells explains on the track, a nickname he got as a kid, and “lor” is a phonetic spelling of the way “little” comes out with a Baltimore-area accent. Wells’ is noticeable when I spend a day with him in his hometown, which he’s never left. He drives me through the Baltimore County community of Middle River, where he lives in the townhome of his childhood that he inherited from his mom. We go deeper into its Hawthorne neighborhood, where his dad was raised, then into nearby Essex, where Wells lived with his grandparents, and back again. “I feel like I’m just telling you the whole story of ‘No Drugs,’” Wells says as he points out landmarks along the way.

As Wells trods through time as his dad on the song, he marks a turning point: “It’s 2018,” he raps. “I’m livin’ in a tent deep in the woods.” Wells takes me there, first down a long, quiet street lined with paths to neighborhoods on the right and tall trees on the left, until the houses start to disappear. “There was this ghost story,” Wells said his father told him of the road. “If you ride down the street at night or go at a certain speed or something like that, you see a ghost.”

We hit Ghost Road’s end, bordered by train tracks into the woods on the left. There’s a slice of a clearing between the tracks and the trees where giant electrical towers hold heavy cables way up above. “When my father was homeless, he slept in these woods,” Wells tells me. Before becoming homeless, Scible rented a house with two of Wells’ uncles, not far from where Wells lives now. When they were evicted, he pitched a tent in this forest, just him and his dog. Wells would drop his dad off here in between the doctors’ and social services appointments he chauffeured him to, in the hopes of securing health insurance and disability income. His dad eventually transitioned to a homeless shelter, but when he was kicked out of it, he went to stay with his mother — Wells’ grandmother — in Florida, where he would later die.

When we pull back into the shallow parking lot in front of his townhouse, I ask Wells about a concern he’s rapped about before — that he talks about his dad too much in his music. I ask him if that’s really how he feels.

“Oh yeah,” he replies rather quickly. “I really do be thinking that sometimes. I always felt like he was a huge impact on my life. Now that he’s passed away, he is on my mind. Obviously, we just talked about him up and down the street for an hour. So, I be feeling like I’m getting on motherfuckers’ nerves sometimes with it, but I also try not to take that to heart too much either because I’m just getting my shit off.”

He says the impetus for “No Drugs in Heaven” was having these kinds of conversations with his girlfriend MaNiya, who joined us on the ride — he remembers him with her. He reminisces. He feels, somehow, responsible for his dad.

“I could have done more to continue to act like I wanted my father in my life,” says Wells, who was periodically distant from Scible. “Maybe he wouldn’t have… You know what I’m saying? Went out and did everything that he did. I’m trying to do right by him by telling his story.”

Wells’ portrait of his father is bustling, full of his good advice and bad choices, of Scible’s simultaneous reverence for and disregard for his son and their family. John Wells would be the first to acknowledge the difficulties of living with an addict. “But I don’t want it to be [like], ‘Oh, he was such a bad person,’” he tells me. “Because that was how people always viewed him while he was alive. I had to look at him as a human to really understand why he was like that. I had to look at his entire life like I did on ‘No Drugs in Heaven.’”

While Wells’ mother was able to pass their home onto him after she moved to Delaware, he has also inherited things from his father. Not his religion — Scible was a Catholic, and Wells practices Islam. And certainly not his vices — Wells doesn’t drink nor smoke. But his musicality — he knows that comes from his dad’s side. Scible always sang loudly, like he wanted people to notice him. On our drive, Wells shows me the elementary school where his dad won a talent show award for his rendition of the Jackson 5’s “I’ll Be There.”

“He got me into music from as long as I can remember,” says Wells, remembering his dad forcing him to sing at parties. “I didn’t want to. I was heavy into rap music.” By the time Wells was 11, he knew he wanted to be a rapper. Before that, he had spent a lot of time writing stories on the computer and printing them out at his grandmother’s house. As he got into Eminem, Lil Wayne, and eventually Kendrick Lamar, rap became a bridge between the creative writing he loved and the music that was in him. His rap style now — mellow but intense, personal but conversational — is clearly the genesis of those three muses and more.

His dad loved rap, too, particularly his. He’d show his son’s YouTube videos to everyone he’d meet, from the homeless shelter to a halfway house. His favorite song of Wells’ was 2015’s “The Jumpoff,” where he raps over the beat of Erykah Badu’s “Bag Lady” for three minutes straight. “My father just thought that was incredible,” says Wells.

For Wells, Scible’s legacy is everywhere — it fills his life, it fills his home. When we meet, roughly ten of his friends are gathered there, excited for Wells to be in Rolling Stone. They plan to celebrate with a trip to Pizza Hut. Someone equates them to a little league team, but really, they’re more like a supergroup.

His engineer, Scotty Banx, sits at the foot of the stairs, a friend Wells made in their high school’s music video club when he was 14. Another artist named Q lounges in a recliner — they met through a mutual rapper friend a decade ago and ended up in long conversations about MCs no one around them seemed to care as much about, like Chicago rappers Saba and Mick Jenkins. Everyone is here, in some way, because Wells is a rapper. These are the bonds he’s forged through music — through his father. And while so much is missing, so much still remains.