Iconic Chicago House Label Trax Records Sued For Decades of Illegal Business Practices

When house music emerged from Chicago in the Eighties, it was a global phenomenon, helping sire rave scenes in the UK and Europe, and blueprinting the global club and EDM-festival scene. A large number of Chicago’s early house classics came out on Trax Records—songs like Phuture’s “Acid Tracks,” Mr. Fingers’ “Can You Feel It,” Frankie Knuckles and Jamie Principle’s “Baby Wants to Ride” and “Your Love,” Adonis’s “No Way Back,” and On the House feat. Marshall Jefferson’s “Move Your Body.”

However, in the four decades since those songs were released, many artists who made Trax Records happen have claimed that they were never paid for their work.

This afternoon, nearly two dozen artists who have released music on Trax—including the label’s co-founder, Vince Lawrence—sued the label, the estate of its co-founder, Larry Sherman, and its current owners, Screamin’ Rachael Cain and Sandyee Barns, a.k.a. Sandyee Sherman. The artists involved in the lawsuit—which includes luminaries such as Marshall Jefferson, Adonis, and Maurice Joshua—allege in court documents and in interviews that Trax didn’t make royalty payments, and in a number of cases released their music without paying them anything at all.

According to the lawsuit, “Plaintiffs may elect to recover statutory damages and are entitled to the maximum statutory damages available for willful infringement …in the amount of $150,000 with respect to each timely registered work that was infringed.”

The suit comes shortly after a legal victory for Trax artists Larry Heard and Robert Owens, who sued and got their masters back, as The Guardian reported last month.

Mulroney refers to the early years of Trax as a “shell game” that included forged signatures, bounced checks, and sketchy (or nonexistent) accounting. Implicated in all these suspect business practices is the label’s founder Larry Sherman, who started the label with Lawrence in the mid-Eighties. (He died in 2020, at 70.)

According to Mulroney, the majority of Trax’s artists show a clear pattern of financial malfeasance on the label’s part. “Larry Sherman said he was going to pay them and never did,” says Mulroney. “Are you going to spend 50, 60 grand to chase it down, knowing there’s no moving forward? What are they worth? You have to go, ‘Is it worth it? I’ll just keep writing.’ And for some of these guys, it was, ‘I’ll never write another song again.’”

During his life, Sherman tended to laugh away these charges: “Where there’s a hit, there’s a writ,” he chuckled, with a cavalier air typical of his interview quotes on the matter, to the Chicago Tribune in 1997. “The kids making these records didn’t know what they should get, and they often didn’t know what their material was worth. And being a good businessman, you don’t say, ‘I think you’re underestimating the worth of your material. Here’s a few thousand dollars more.’”

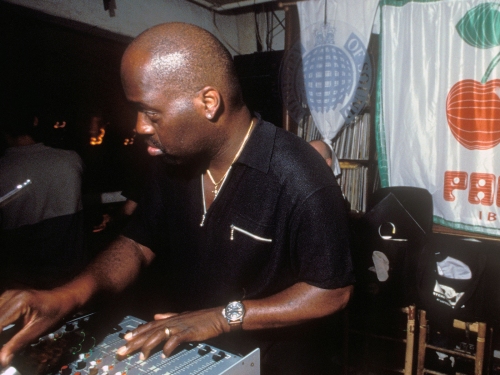

Sherman’s career in the music business began in 1982, when he purchased Musical Products, Chicago’s only pressing plant. At the time, a number of young, Black local DJs were beginning to make 12-inch singles—-minimalist, drum machine and synth-driven records inspired by the sets being played by local DJs such as Frankie Knuckles, Ron Hardy, and the rotating lineup of WBMX-FM’s Hot Mix Five. The style was dubbed “house,” after Knuckles’ club the Warehouse, open from 1977 to 1982, and the most minimalist of these records were dubbed “trax.”

Sherman founded Trax with Lawrence, a DJ and producer, and his collaborator Jesse Saunders. Lawrence says he quickly noticed that Sherman had a habit of not paying musicians. “At some point, it was like, “Hey, I’m not getting paid. I’m gonna go do some stuff that gets paid, I’ll bring you some artists or some records here and there.” I hoped it would grow to a point where I could get my cut, and it never really happened.” Lawrence left the label in 1986.

The suit filed this afternoon is hardly the first time a Trax artist has accused the label of wrongdoing. One artist who is involved with the suit, Jamie Principle—whose classics “Your Love” and “Baby Wants to Ride,” both produced by the late Frankie Knuckles, are in the Rolling Stone list of the top 200 dance songs of all time— told 5 Magazine in 2011, “They never had the rights to release any of my stuff . . . They literally just stole my stuff.”

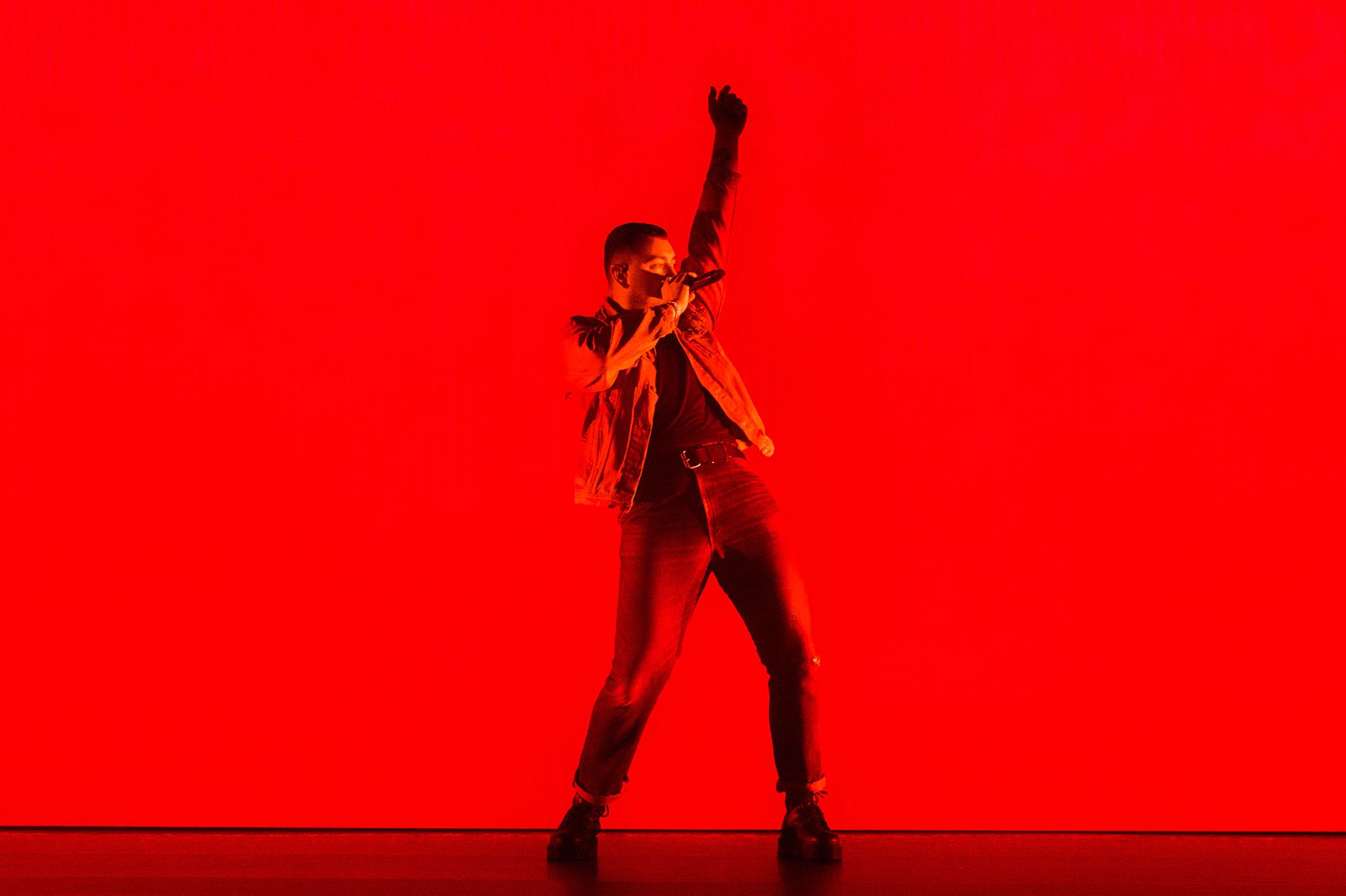

Marshall Jefferson, who is a plaintiff, asserts that he was never paid by Trax Records for his classic house anthem “Move Your Body”—and that it was released by the label without his consent.

“We didn’t have record companies in Chicago,” Jefferson recalls. “It was totally uncharted territory. We didn’t know how to do record deals or anything like that, so we were basically lambs to the slaughter. He wouldn’t tell us anything. We got no statements. We just wanted to get our music out.”

Jefferson had originally wanted to issue “Move Your Body” on his own new label, Jam Line, and says he paid Sherman $1,500 to press a thousand copies, and that Sherman took the fee and the master recording without pressing the record. “He didn’t like it. He thought it was a waste of time,” says Jefferson. Months later, Sherman was showing some British reporters around the house clubs. “Every club that he went to, they played ‘Move Your Body’ off cassette,” says Jefferson—because Sherman had refused to press it for Marshall’s label. “Of course, the crowd reaction was off the chain. Everybody knew it and it wasn’t even out yet. The next day he pressed up ‘Move Your Body’ on Trax Records”—without even securing Jefferson’s permission or paying him for it. (Jefferson says he has been able to acquire some publishing royalties through the publishing company Ultra Music, but nothing else.)

Hits like “Move Your Body,” were the result of a scene where, as Lawrence recalled, “We could put out anything. That gave us the ability to experiment, which led to innovation. Things like acid house, in the then-current climate, were not considered normal records. There were no records like that. Most record companies were trying to put out records that remotely resemble other records, at least. And we were in a position to just see what happened. We put out records with just drums—several. And they were successful.”

As Chicago house began to take off during the UK’s late-Eighties rave explosion, Sherman kept the music’s popularity overseas hidden from his artists. “At that point, it was fairly easy for him to suppress me knowing that it was hugely successful,” according to DJ Pierre, a member of Phuture, whose “Acid Tracks” introduced the freaky “acid” sound, which became a global dance-floor phenomenon. “It wasn’t like you had all these other sources to dispute that. I had no idea that our music was migrating to London.” He found out when a London journalist told him: “I was like, ‘Wait a minute. This guy here has been ripping us off,’” said Pierre.

According to many house music artists, Trax’s strong-arm tactics didn’t end when Sherman was forced to sell the label to his wife, Screamin’ Rachel Cain in 2006, as part of their divorce settlement. Several people who spoke to Rolling Stone have accused her of threatening defamation lawsuits as a deterrent to artists discussing Trax’s alleged wrongdoing, with many artists growing discouraged enough to give up seeking payment or rights for their work. Earlier this month, Mulroney says that he himself received a cease-and-desist for defamation, filed from a court in Louisiana.

According to the filing, “Rachael Cain committed Fraud on the Trademark Office,” pointing to her registration of the Trax Records logo and her attempt to register the name Dance Mania, another iconic Eighties Chicago label. “Vince Lawrence came up with the name Trax Records and created the now iconic logo,” the filing states. “It is this creation that is one of Vince Lawrence’s proudest achievements, one that he expected to be equated with for the rest of his career. As long as Sherman was alive, Sherman never attempted to trademark Vince Lawrence’s Trax Records.”

Numerous people involved in the Chicago music scene also take issue with Cain’s attempts to register for trademark other important Chicago house labels founded in the Eighties, such as D.J. International, as well as the name of an entire genre – “juke,” a fast, hyper-syncopated Chicago dance-music style that became popular in the 2010s. (As of press time, Cain has not responded to a request for comment.)

Lawrence says that Cain has also hijacked intellectual property rights. He says he recently discovered that “Love Can’t Turn Around,” a song he’d co-written that became a top-ten UK hit in 1986—had been registered by Trax without his knowledge or consent to Screen Gems Publishing, which specializes in music licensed for film and TV.

Trax has had a long history of financial trouble. As the Chicago Tribune has reported, In 1991, the company declared bankruptcy after a distributor that owed them $4.5 million went under. But by 1997, Trax began to license its wares to other companies, with Cain acting as the label’s president beginning in 1998.

In 2002, Trax signed a licensing agreement with the Canadian label Casablanca (not to be confused with the Seventies imprint with Kiss and Donna Summer). When a sampling of Trax classics were reissued on CD in 2004 through Casablanca, Lawrence says, “I never saw a penny.” In a recent statement published on Facebook, Cain claimed that this instance of nonpayment was the fault of Casablanca.

For Lawrence, the struggle for financial restitution has been going on so long, it now spans generations. “I’m communicating with heirs of people who were signed to Trax Records,” he said. “We’re just trying to get everybody the rights that belong to them. I believe that [the songs are] important. And I want my catalog to be where it belongs.”