How the U.S. Can Get Ahead of a Spreading Disease Caused by Fungal Spores

A regional disease in the American West is about to get a lot less regional as the planet heats up, scientists warn.

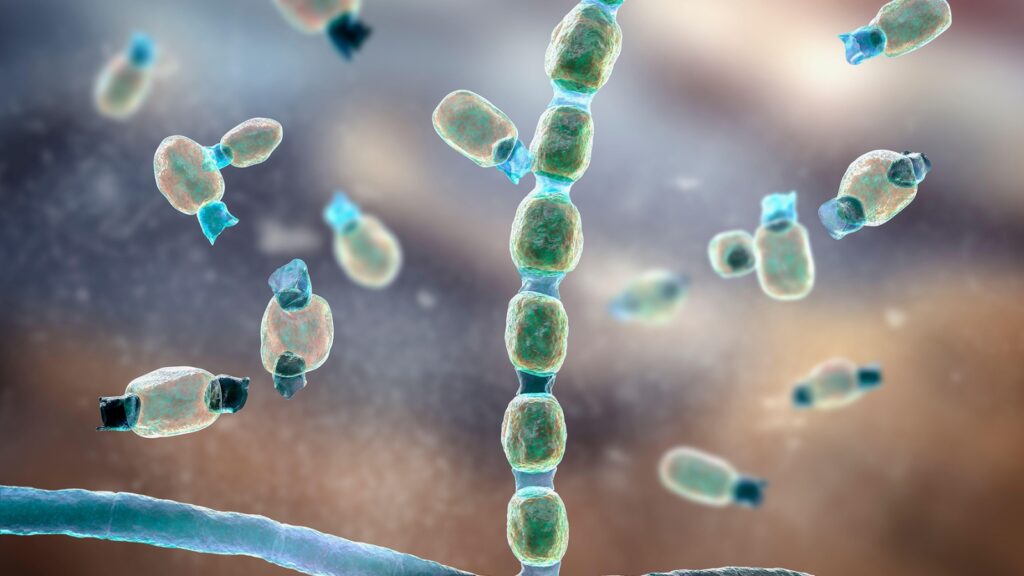

It’s Valley Fever, a lung and throat disease caused by the coccidioides fungus. The fungus — basically, a dirt spore — isn’t new and it isn’t contagious, but many doctors and nurses aren’t very good at diagnosing the respiratory disease it causes.

So it could spread largely unnoticed, via contact with dirt and dust, unless and until we revamp our health system, which lacks both the skills and the testing resources.

While Valley Fever isn’t a new problem, it’s a growing one — and it’s gotten a lot of attention lately owing to HBO’s popular new show The Last of Us, which depicts a fungal disease that turns people into zombies. “I think there has been more popular media coverage of fungal infections in the last few weeks, thanks to The Last of Us, than I could have imagined,” says Ilan Schwartz, an expert in infectious diseases at Duke University.

Climate change is drying out the western United States, steadily expanding the hot, dry region where coccidioides — the fungus that causes Valley Fever — thrives. The fungus could head east and north, deeper into Washington State and Texas.

The danger is that the fungus will spread faster than the U.S. healthcare system can adapt. “Given what we know about the expansion of Valley Fever — and the important threat that it imposes to people and animals — I do think this needs to be taken extremely seriously,” Schwartz says.

Coccidioides is most common in the soil of California’s Central Valley and nearby desert areas. Breathing in coccidioides spores can cause a hard-to-diagnose and occasionally severe respiratory infection that, fortunately, isn’t contagious. But in a small number of cases, infection can spread to the nervous system, skin and bones. Pets are at risk, too — especially dogs.

State authorities typically report around 20,000 Valley Fever cases annually to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Officially, around 200 people die of the disease every year.

But both figures are almost certainly huge undercounts, as many states don’t include Valley Fever on the list of diseases they report to the CDC. Most problematically, Texas doesn’t report Valley Fever, even though the dry soil of the state’s western half is pretty hospitable to coccidioides. “The true number of cases each year is around 150,000,” Schwartz says. We don’t know the actual number of deaths, but it’s almost certainly more than the official figure.

Clinics and hospitals in the places where coccidioides is most prevalent — in particular, the Central Valley and parts of New Mexico and Arizona, including Phoenix — know what Valley Fever looks like and usually can confirm a case, via a blood test, within a day or two.

There’s no so-called “point of care” test for Valley Fever. Analyzing blood samples for the fungus requires complex machinery that’s usually only present at special laboratories. There are plenty of those labs in say, California and Arizona—meaning swift detection can lead to swift diagnosis and swift treatment with anti-fungal medication.

That’s not the case in other parts of the country, where getting a blood sample tested for coccidioides could take days if not weeks. There’s also a dangerous tendency for clinicians everywhere but out West to mistake Valley Fever for some other, more common, disease. “It presents with an illness that can’t be distinguished from bacterial or viral infections,” explains John Galgiani, a Valley Fever expert at the University of Arizona.

Misdiagnosis could further delay testing and treatment and increase the risk of a serious outcome. Long-term illness. Even death. “A small percentage of people get very very sick from this,” Galgian says. “Early diagnosis identifies those more problematic cases.”

Doctors, nurses and health officials across the United States need to get up to speed on Valley Fever. “The infection can masquerade as many other diseases,” Schwartz said.

Mohanad Al-Obaidi, a University of Arizona infectious diseases expert, recommends three steps. First, more states need to start reporting Valley Fever cases to the CDC so that everyone has a better sense of where, and how quickly, the disease is spreading.

The second priority is more fundamental: “Expanding our understanding of the biology of coccidioides,” Al-Obaidi says. More and deeper research into the fungus and the fever it causes could, in turn, support the third step — the development of faster testing methods and, most promisingly, a vaccine.

While there isn’t currently a vaccine for human Valley Fever, an animal vaccine is under development at the University of Arizona. Galgiani says he expects the U.S. Department of Agriculture to approve it within a year.

The animal vaccine could form the basis of a human vaccine. “There’s no reason it can’t go into a human,” Galgiani says, although the approval process — through the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the CDC, is different and much more stringent.

It’s an open question whether Americans would line up for a Valley Fever vaccine. The good news, on the potential vaccine-uptake front, is that only the most vulnerable people in endemic regions would need a Valley Fever jab. Farmers and construction workers in California and Arizona, for example. Surveys indicate those subgroups are already open to vaccination, Galgiani says. “People are a lot more sympathetic in the endemic region.”

If there’s a major obstacle to a better, wider Valley Fever response, it’s that the disease still seems far-away and unimportant to most Americans. “If a patient does not have a clear exposure to southern California, New Mexico or Arizona, they are often considered to not have any risk,” says Patrick Mazi, an expert in infectious diseases at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

But the endemic region is expanding north and east as our deserts spread north and east. Old thinking and cumbersome institutions need to at least keep up with a changing climate — or, better yet, get ahead of it.

Yes, that’s going to cost money. But it’s worth it, Mazi says. “The Covid-19 pandemic showed the negative impact of underfunding the public health system—and it doesn’t seem we’ve totally learned our lesson from that. There really needs to be a focus on rebuilding the public-health infrastructure so we can be better prepared for future infectious diseases.”