How an Alleged Con Man Tore Apart One of the Nineties’ Biggest Bands

O

N MARCH 4, 2020, guitarist Chad Taylor stood on a beach outside of the Hard Rock Hotel in the Dominican Republic. He fired up a Cuban cigar and stared out at the vast ocean. After years of bitter infighting and nasty legal battles, his band Live — best remembered for their Nineties hits “Lightning Crashes” and “I Alone” — was finally reunited and back on the road. Live had just wrapped up a successful co-headlining tour with Bush, there was talk of cutting a new album, and they were in the Caribbean to play a lucrative private gig.

“Life doesn’t really get any better than this,” Taylor recalls thinking to himself. “I worked so hard to get this. Let’s enjoy this. Tonight we’re going to jump onstage, play for about 15 minutes, and we’re going to get paid an obscene amount of money. This is perfect.”

When he looks back on it now, that moment on the beach was the last time he was truly happy. In the months that followed, nearly every single aspect of his life fell hopelessly apart. First, the pandemic shut down the global concert industry later that month, robbing Taylor of his only solid source of revenue. Then, a series of interpersonal calamities and alleged betrayals led to the breakdown of the band. As far as what exactly happened — the details change depending on who you talk to.

What we do know is this: In late 2019, a man named Bill Hynes, who’d been Taylor’s partner in numerous business ventures throughout the prior decade, was arrested and charged with robbing, stalking, and brutally beating a young woman employed at their company. And in June 2022 — for reasons he’s never publicly articulated but that are likely related at least in part to the turmoil that Hynes brought into the band’s world — Live frontman Ed Kowalczyk fired Taylor via a terse Instagram post. “As of last evening, I own 55% of Live,” the singer wrote. “Chad Taylor is fired. He will never stop the music again.” Kowalczyk fired Live drummer Chad Gracey and bassist Patrick Dahlheimer, too — albeit in a less public fashion. Taylor remains on good terms with Dahlheimer, but the rest of the band now communicates mostly through lawyers. (Kowalczyk declined to comment for this article.)

This is hardly the first time in music history that a band has melted down due to personality conflicts, clashes over money, and legal battles. Wildly successful groups from the Beatles to the Police to Fugees have faced some combination of those issues, and most of them eventually got past it and repaired the damaged bonds. That’s hard to imagine in this case. The onetime best friends in Live are now so bitterly divided on every imaginable topic — even the most basic facts of what transpired over the past few years — that speaking with them feels like asking Marjorie Taylor Greene and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to sit down for a friendly chat about the root causes of Jan. 6. (In fact, one of the former bandmates is a Trump supporter, while another calls himself a “bleeding-heart liberal.”)

Let’s start with Taylor. If you ask him, it was Hynes who destroyed the band. Taylor now describes Hynes as a gifted con artist, one who he claims stole more than $10 million from him and his bandmates, leaving him practically broke.

“I was a sucker,” Taylor says. “I have people that depend on me, and I trusted a person that hurt us. I failed as a husband. I failed as a father. I failed the families of my bandmates. I have yet to forgive myself.”

If you ask Gracey? “Everything that’s happened is because of Chad Taylor,” he tells me from Las Vegas, where he’s in town to attend the AVN Adult Entertainment Awards. “He’s a raving, pathological narcissist that’s made Bill the boogeyman for everything that’s happened in his life. I don’t want to deal with him anymore at any level.”

And Hynes? He agrees with Gracey. “Chad Taylor is a crazy drunk,” Hynes tells me. “I regret ever meeting him.”

Since cutting a deal with prosecutors in September 2022, in which he pleaded no contest to felony criminal trespass, felony theft by deception, two counts of felony forgery, misdemeanor stalking, and misdemeanor simple assault, Hynes has been held under house arrest at Live’s former corporate headquarters in York, Pennsylvania. We’re speaking over Zoom, with his lawyer looking on. “[Taylor] is a selfish individual,” Hynes continues. “He only looks out for Chad Taylor … and I’m probably one of the nicest, kindest people you’ll ever meet.”

Through all of this, Live has lived on — thanks to Kowalczyk, who has done his best to stay above the ugly squabbling that has consumed his former bandmates, and has focused, instead, on rebooting Live with three other musicians. The new iteration of the band hit the road in late October, although, so far, their gigs have largely been limited to casinos in tertiary markets like Mount Pleasant, Michigan, and Bensalem, Pennsylvania.

As Kowalczyk and his new bandmates gear up for a show at Florida’s Busch Gardens Tampa Bay and a couple of summer festivals in the Netherlands, Taylor sits on the second floor of his guitar shop, Tone Tailors, in Lititz, Pennsylvania, where $4,000 Fenders line the walls and a road case with a fading Live sticker sits in a corner. A sign on the wall says “No Stairway to Heaven,” referencing a classic moment in Wayne’s World. Songs by the Eagles and Fleetwood Mac play in the background as Taylor’s employees prepare to open up the shop for the day.

“I was a sucker,” guitarist Chad Taylor says. “I have people that depend on me, and I trusted a person that hurt us. I failed as a husband. I failed as a father. I have yet to forgive myself.”

“It has been very weird to see Ed go out and play shows with the new guys in the band,” says Taylor, 52. “I had a panic attack recently: ‘Am I late? Am I supposed to be in Buffalo, or wherever? Did I screw up?’ Patrick and I joked that we were going to show up at the first show and stand outside with signs that said, ‘Looking for work.’ ”

Taylor has been up since 4:30 a.m., poring over legal documents. There are dark bags under his eyes and specks of gray in his long beard and thinning brown hair. He speaks at a rapid clip as he goes through the saga of what happened to Live — a story he’s still trying to wrap his head around.

“I’m just sitting here,” Taylor says. “Trying to figure out how my band broke up over all this.”

WHEN IT COMES to Nineties alt-rock bands, Live falls somewhere between Matchbox 20 and Creed on the cool meter. Even at the peak of their popularity, when they were packing arenas, critics had virtually no use for them. “Song after song depended on the same groove — soft verse, LOUD CHORUS,” read a typical concert review in a May 1995 issue of Rolling Stone. “But unlike, say, the Pixies’ blare, Live’s volume twiddling felt as predictable as a gag in a Jim Carrey movie.”

Live were a major presence on MTV in the era between grunge and teen pop, but most young viewers of the time couldn’t spit out the name “Ed Kowalczyk,” let alone those of his three bandmates. They largely just knew the super-intense bald guy who delivered lines like “And to Christ a cross/And to me a chair” and “Her placenta falls to the floor” without a hint of irony.

That anonymity didn’t stop Live from playing both Woodstock ’94 and Woodstock ’99, filming an episode of MTV Unplugged, appearing on the cover of Rolling Stone, selling millions of albums, and landing an incredible 17 hits on the Billboard Alternative Airplay chart over a period of 12 years. By the turn of the millennium, everyone in the band was a millionaire several times over.

“Every friend and family member under the sun was suddenly starting a business or asking for a loan,” says Taylor. “I’ve furnished several houses that weren’t my own. I’ve bought several cars that weren’t my own.”

That lavish lifestyle, and the problems that come with it, would have been beyond imagination to the four members of Live back when they were teenagers growing up together in the small working-class town of York in the mid-Eighties. Taylor and Gracey bonded early over their shared love of alternative bands like the Cure, Joy Division, and Depeche Mode — especially since most of their classmates were into hair-metal groups like Quiet Riot and Ratt. “I spent every single weekend I possibly could at Chad’s parents’ house,” Taylor says. “I’d sleep next to his bed in a trundle bed. We’d watch John Hughes movies like Weird Science. We were inseparable.”

On this, if nothing else, Gracey is in agreement with his former bandmate. “We were best friends,” the drummer says. “Sometimes today I’ll hear an old U2 song and think, ‘Oh, I used to listen to that with Chad.’ ”

In the eighth grade, they recruited their buddy Patrick Dahlheimer to play bass and booked themselves at a school talent show where they performed an instrumental medley of U2’s “Like a Song” and Newcleus’ “Jam on It.” In the audience was a kid named Ed who used to chase Taylor around the playground and try to beat him up. “I asked for a hall pass to go to the bathroom, and I was walking down the hall, and I saw Ed,” says Taylor. “I was like, ‘Oh, my God, we’re going to fight again.’ My stomach turned inside out since I was so scared. And he walked up and he was like, ‘Hey, man, I would love to play with your band.’ ”

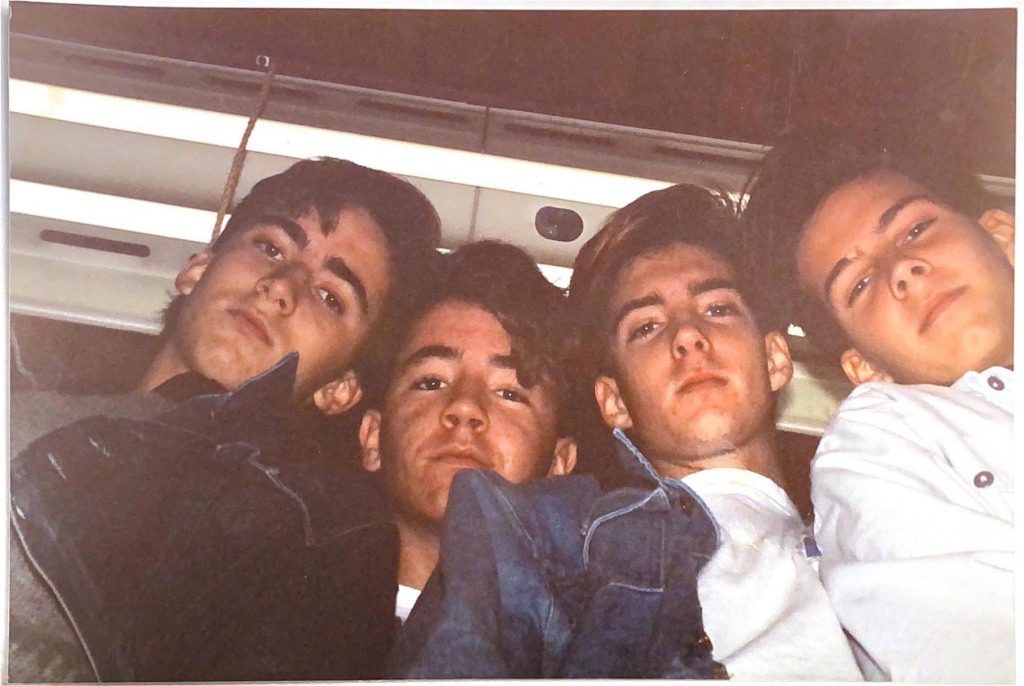

Kowalczyk, Dahlheimer, Gracey, and Taylor (from left) in the small town in Pennsylvania where it all started, 1988.

COURTESY OF ACTION FRONT UNLIMITED INC.

The classic lineup of Live was complete before they entered high school. They called themselves Public Affection — the name Live wouldn’t come until 1991 — and the next few years were marked by slow progress. In time they were opening for national bands like the Pixies, and original songs slowly began replacing covers in their set lists. They self-released their debut LP, The Death of a Dictionary, as teens in 1989, but they didn’t really find their sound until two years later, in 1991, when they teamed up with Talking Heads guitarist Jerry Harrison to cut an album called Mental Jewelry for a subsidiary of MCA.

Leadoff single “Operation Spirit (The Tyranny of Tradition),” written by Kowalczyk and Taylor, wound up in MTV’s Buzz Bin, suddenly exposing Live’s music to fans all across America. When it first aired, the band was staying at the Phoenix Hotel in San Francisco — the same hotel as Nirvana, who had a show in town that night. “Nobody knew who Nirvana was at that point,” Taylor says. “But they stood shoulder to shoulder with us after their gig, drinking beers, waiting for the video to come on. At midnight, they played ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ and ‘Operation Spirit’ back to back. It was the craziest thing.”

Live’s single eventually reached Number Nine on the Alternative Airplay chart, and they spent so much time touring behind it that their next album, Throwing Copper, didn’t come out until weeks after Cobain’s death in 1994. Leadoff singles “Selling the Drama” and “I Alone” exploded on rock radio, but they hit another gear with “Lightning Crashes.” Written largely by Kowalczyk, the achingly sincere song is about a grim moment in a hospital where one woman dies at the moment another woman gives birth down the hall, completing the cycle of life and death.

“I remember entering the room and hearing him sing the word ‘placenta,’ ” Taylor says. “I was like, ‘What the hell is he singing about?’ But back in middle school, when everyone else was at home trying to find their dad’s Playboy, he was reading Eastern philosophy books. He was singing about mysticism and our spiritual journey.”

Throwing Copper ultimately sold more than 8 million copies, becoming a mainstay of the post-grunge scene. But the critics still had little use for them. “We were never press darlings,” Gracey says. “We had small-town, inexperienced management, and we deferred to them.”

When it came time to craft a follow-up, the band dumped Harrison and leaned further into Kowalczyk’s mysticism. They called their next album Secret Samadhi and released a turgid ballad called “Lakini’s Juice” as the leadoff single — both references to philosophical concepts that were unfamiliar to many rock fans at the time. “All these people were like, ‘You can’t call the song ‘Lakini.’ You can’t name the record Samadhi,’ ” Taylor recalls. “Then the worst thing that could possibly have happened to our egos happened: It came out and debuted at Number One. In my mind, as a pretty young guy, I was like, ‘Well, the world can just fuck off, because you’re wrong.’ ”

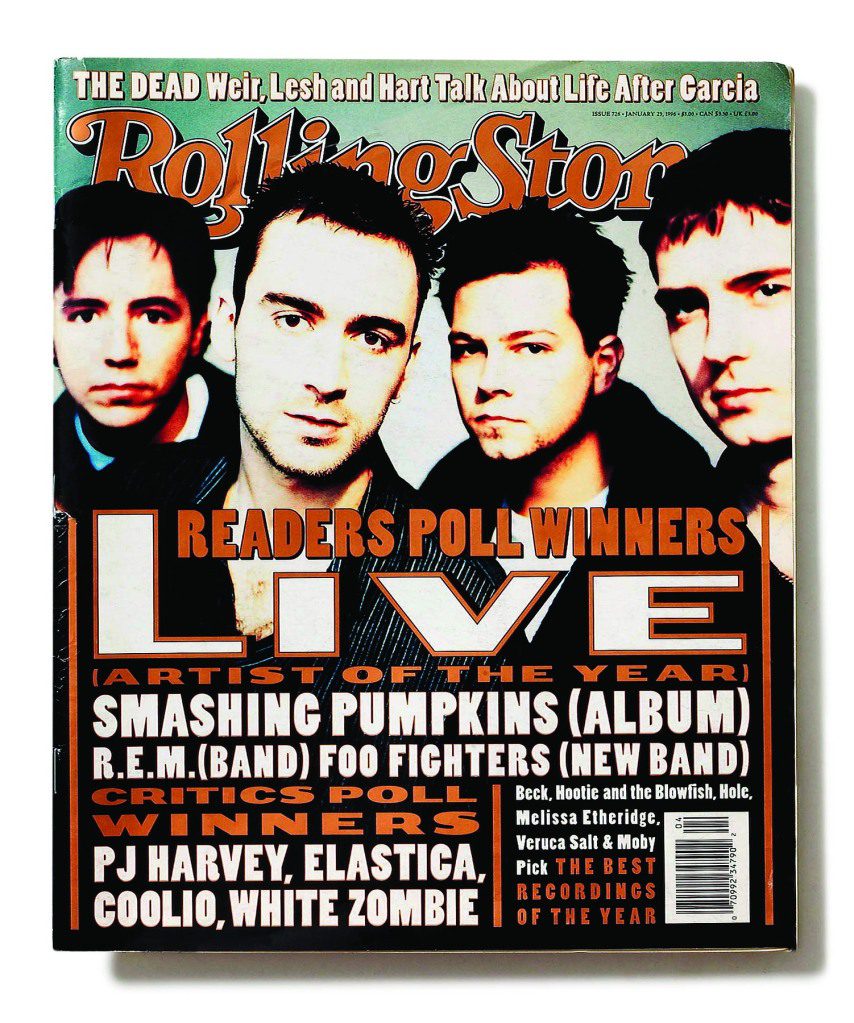

Live’s Jan. 25, 1996, Rolling Stone cover.

Behind the scenes, however, the band was falling apart. Taylor says Kowalczyk insisted on taking the lion’s share of the publishing money since he was writing most of the songs, causing tension between him and Taylor that never truly went away. On Live’s next album, in 1999, Taylor says, the singer went further, telling the band he would write the songs entirely by himself, using them as mere support musicians. “That ended my creativity in the band,” says Taylor, still pained by the memory. “I felt like a married couple where someone says, ‘I’m no longer going to have sex with you. But we’ll stay married.’ It was one of the saddest moments of my life.”

Gracey feels that Kowalczyk was right to demand sole credit. “Ed has written every lyric and every melody for Live ever, and Chad would try to take credit,” he says. “Chad might come up with a guitar idea that would become a song, but he didn’t write the song.”

He agrees, though, that the move caused major waves in the band. “Chad told me he hung himself outside a balcony and nearly jumped when we were on tour in New Zealand,” Gracey says. “He’s always been very dramatic about stuff, so I don’t know if it even happened.”

Taylor doesn’t expressly deny the incident and concedes that he had a serious drinking problem in the early 2000s; he says he now has “a healthier relationship with alcohol” and a more stable outlook after undergoing treatment. And he’s adamant that his mental-health challenges in that era were about more than songwriting disputes.

“I’ve been relatively open about my own struggles with self-medication and overcoming the challenges of being a creative person,” Taylor says. “Like many of my peers, I feared I would commit suicide if I did not establish healthier practices for myself.… To characterize these complex issues as related to songwriting, or even my relationship with Ed, tells you how little Gracey understood about me and our creative process.”

TONE TAILORS IS a small part of the 96-acre Rock Lititz campus, right on the edge of Amish Country. The overall campus is one of the nerve centers of the touring industry: Beyoncé, U2, Taylor Swift, Lady Gaga, Usher, and countless others have used its arena-size rehearsal halls to prep major tours. There’s an actual school in the complex devoted solely to pyrotechnics, a studio the size of two IMAX theaters, and a luxury hotel so visiting acts never need to leave the campus. Taylor walks me down the enormous halls and points out museum-ready rock artifacts like the cannon that gets wheeled out when AC/DC plays “For Those About to Rock (We Salute You),” and the giant model airplane that Roger Waters flew over the stadium crowds on his 2010 Wall tour.

The campus is a beehive of activity with credentialed employees scurrying about in every direction, but Taylor no longer has a need for any of the services offered here: His main priority is dealing with the lawsuits he now faces in the aftermath of Live’s implosion, trying to figure out how he’ll pay his mounting pile of bills, and worrying about what might happen once Hynes is freed from house arrest later this year.

We hop into his Jeep Cherokee and head into town. On the way, we talk about the first time Live collapsed. Taylor goes on about the rise of teen pop, the collapse of the industry due to Napster, and MTV’s decision to abandon virtually every Nineties band once the ball dropped on the new millennium. On top of all that, they had the miserable luck of scheduling their sixth LP for release just seven days after 9/11. “What a horrible time period,” he says. The group limped forward with new albums released in 2003 and 2006, but sales were anemic; Live were just as unpopular in the age of Fall Out Boy and Panic! At the Disco as they were in the days of Backstreet Boys and Korn. It came as no surprise when they called it quits in 2009. “We broke up over email,” Taylor says. “Ed sent out a letter and was like, ‘I think we ought to put this band on hiatus.’ We all responded in about 30 seconds and went, ‘Great idea.’ There wasn’t one of us that fought to keep it together.”

Shortly after Live split up, with some of the former bandmates looking to get into the TV/movie business, their mutual attorney introduced them to Hynes, who was looking to get into TV, too.

The story from this point varies wildly depending on who is speaking. What’s clear is that the accusations against Hynes are voluminous to the point that combing through all the police reports, criminal complaints, and courtroom filings — plus the articles published in the York Daily Record, which has been tirelessly pursuing this story for years — would take several hours. But a July 29, 2019, Protection From Abuse document on file in York County’s Court of Common Pleas stands out as particularly harrowing.

The document tells the story of a woman who worked for Hynes at United Fiber and Data, a fiber-optics company he founded with Taylor, Gracey, and Dahlheimer. She was in her early twenties when she met Hynes, who was two decades older, and she had no experience with telecom, but he hired her as an office assistant in 2014. “One night he invited me over,” she told the court. “He attacked me, we had sex. It was not consensual … the next thing I knew, I was in a relationship with my boss. Any fights we had personally, he would take it out on me through work … basically, my employment was dictated by my personal relationship with Bill.”

There was much that this woman — who has asked us not to reveal her name or other details about her life, citing ongoing fears for her own safety — still didn’t know about Hynes at this point. She didn’t know that he had a felony conviction for check forgery and at least one bankruptcy in his past, nor did she know about what she now describes as his titanic temper. “When I look at the level of his duplicitous actions,” says Taylor, “it’s nearly inconceivable for me to even imagine being that evil.”

According to the victim, Hynes would go into a violent rage at the tiniest provocations. “If I ever tried to defend myself or speak up, he would fire me or threaten to fire me,” she told the court. “He would shove me around in public. Once, in the lobby of the Encore in Las Vegas, he shoved me so hard I fell over. Later in the hotel room, he shoved me again. I fell back and hit my head on the hard marble floor. He then got on top of me and put his hand over my mouth and nose so I was not able to breathe.”

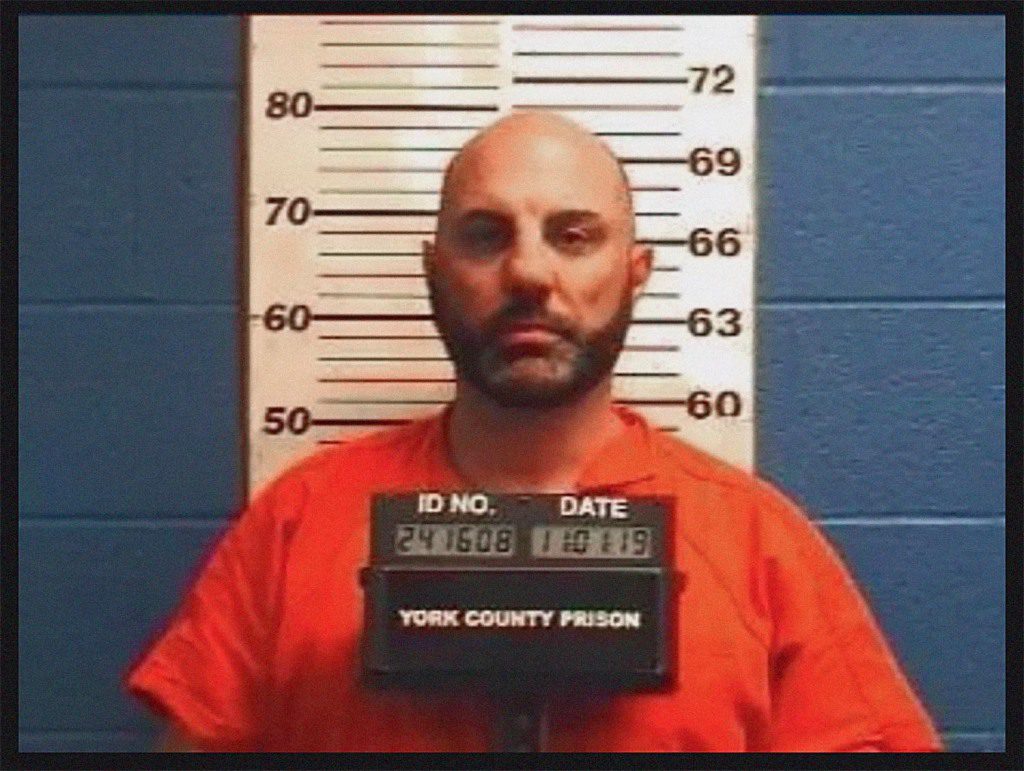

Hynes’ 2019 mug shot.

YORK COUNTY SHERIFF’S DEPARTMENT

During a 2018 work trip to Fiji, she alleges, he attacked her. “He lunged at me full force,” she wrote. “He was on top of me, and his hands were around my neck. He is squeezing my neck and he said, ‘Guess who’s going to die tonight?’ ” She told the court that she eventually managed to break free and find shelter in another guest’s room, where she called local authorities. They issued a warrant for his arrest, she says, but fearing he’d make bail and come and kill her, she declined to press charges. When she returned to America, she says, he continued to threaten her.

In 2019, after she went to police, Hynes was arrested on charges that included stalking her, putting tracking devices on her car, placing listening devices in her home, and even forging her signature on mortgage documents tied to her own house, causing her financial ruin.

Earlier this year, after significant delays in the legal system due to Covid, Hynes cut a deal with prosecutors. When I bring the matter up over Zoom, Hynes tenses up. “We’re not going to talk about my ex-girlfriend,” he says. “That was a complex and difficult relationship. I think both parties just want to move on with their lives, and be happy. That’s what I wish for all of us.”

That’s about all he’ll say about the crimes he was accused of. “I pled no contest to five charges,” Hynes continues. “It was the quickest way forward, and not to drag anyone through a long and expensive lawsuit. I did not admit any guilt.” His lawyer cuts me off when I press him on the specific charges leveled against him in court.

“My goal has always been to be free from my abuser and live a normal, healthy life,” the victim tells Rolling Stone in a statement. “In the end, I felt the only way for me to achieve that was by getting a [Protection From Abuse Order]. I stand by everything that was in my petition.” She adds: “I was also prepared to testify about my experience again, at the criminal trial. There was apparently over 600 pages of evidence that the police compiled. Unfortunately, after nearly three years of delays, a plea deal was agreed to without my consent.”

THE NAME “BILL HYNES” causes Chad Taylor to shudder today. But when they first met back in 2010, Taylor saw Hynes as a potential savior. Hynes not only offered them the chance to generate money away from Live, but he was also willing to fund Taylor’s new band, the Gracious Few — an alt-rock supergroup of sorts featuring Dahlheimer, Candlebox singer Kevin Martin, and Candlebox guitarist Sean Hennesy. Passing himself off as a wealthy real estate investor (even though, according to public records, he’d just declared bankruptcy), Hynes promised to fund a recording session in Sausalito, California, with Live’s former producer Jerry Harrison, housing for the bandmates’ families, and a tour.

It was only when they arrived in Sausalito along with their gear, Taylor claims, that they learned every check Hynes wrote for the project had bounced. “We were stuck,” Taylor says. “Talk about making an awkward call to your wife. I had to say to her, ‘I need $10,000 right now to pay for the studio deposit. Oh, and I need another $15,000 for the housing.’ And she’s like, ‘You mean out of our personal checking?’ ” (Hynes disputes nearly every aspect of this story. “No checks bounced,” he says. “And they were responsible for paying all those people. I gave them $43,000, and they paid me back.”)

Taylor says he pledged to never speak with Hynes again when it became clear the funds were never coming. Had he stuck with that pledge, the past decade of his life would have gone very differently. But a year or so later, he says, he got a call from Chad Gracey with Hynes on the line — begging for forgiveness, citing the stress of a recent divorce, and offering to make it right with Live. “He was pretty compelling,” Taylor says. Soon, Taylor had agreed to “a few projects,” including real estate opportunities and the fiber-optic company.

Today, Taylor alleges that Hynes was a talented grifter who was mainly interested in using Live as a means to bilk investors, hang out with celebrities, and bring young women into his orbit. Hynes counters, calmly and without hesitation, that he was always the man he claimed to be. “I’m a real estate investor,” Hynes says. “I have such great credit that I could walk into Mercedes right now and walk out with a $300,000 car if I wanted to.”

Hynes gives Gracey, Dahlheimer, and Taylor (from left) a tour of the Reading Outlet Center, which they bought for $1 million in 2011 with plans to renovate it as an apartment and retail complex. The building later collapsed.

Ryan McFadden/MediaNews Group/”Reading Eagle”/Getty Images

But some of Hynes’ claims are very difficult to square with the historical record, including his assertion that he’s only declared bankruptcy a single time. Public records show five bankruptcies for a William T. Hynes of Nazareth, Pennsylvania, between 2004 and 2012. When confronted with this, Hynes says he was the victim of multiple identity thefts, which he blames for the other bankruptcies in the system. “One of the people doing the identity thefts was another William T. Hynes,” he says. “Somebody said it may or may not be a half brother, but I don’t know if that’s true or not because I didn’t grow up with my father.”

He also says he’s never had a lien, a judgment, or a collection against him at any point in his life. Public records, however, show 11 liens that add up to $91,000 or more between 2002 and 2017 for William T. Hynes of Nazareth, Pennsylvania. “I don’t have one lien on me whatsoever,” he says indignantly. “I’ve never had a lien on me.”

Hynes reentered Taylor’s life at a desperate time. The Gracious Few dissolved after one album, and Taylor reformed Live in 2012 with Gracey and Dahlheimer — and Chris Shinn, son of billionaire Charlotte Hornets owner George Shinn, as their singer. An Ed Kowalczyk-free Live, however, was a difficult sell to most fans. They quickly found themselves on the Nineties nostalgia circuit with B-list acts like Everclear and Filter (and fighting Kowalczyk in court over the use of the band name).

“When we started, the original concept was ‘Let’s take the bones of this band that has a built-in audience, and let’s slowly merge it into something unique,’ ” Shinn told Rolling Stone late last year. “But I came to find out it was all about making money for them.”

Taylor, naturally, begs to differ. “That’s so disingenuous,” he says. “Respectfully, a guy that has a trust fund and has never worked a job in his life can’t understand that we make our living as musicians. We have to tour.”

Soon, though, the band members had to figure out other ways to supplement their income. Taylor tried producing movies, like the 2010 Ernest Borgnine-Cybill Shepherd film Another Harvest Moon; later, in 2011, he and the other members of Live (minus Kowalczyk) sold their publishing stakes in the band’s catalog for $1.9 million. “I could have gotten twice as much in this market today,” Taylor says. “But I went to the boys and said, ‘We’re going to all go broke. We aren’t making enough money to live.’ ”

Right around when Taylor, Gracey, and Dahlheimer sold their publishing stakes, Hynes was back with a new set of schemes. “I think that’s why he wanted back,” Taylor says. “He wanted a shot at this fuckin’ money.” One of the more outrageous ideas that he says Hynes talked the three former bandmates into was investing $1 million with him into a building in nearby Reading, Pennsylvania. “I’m not shitting you,” Taylor says. “The building fuckin’ imploded and fell down.”

“I have deep regrets that I wasn’t more attuned to their relationship,” Taylor says of Hynes’ alleged violent abuse of their employee. “Those images will never leave my mind.”

Undeterred from that disaster, they took some of the remaining money — plus a ton from deep-pocketed outside investors — and formed United Fiber and Data. The idea came from Hynes. “At first I was like, ‘fiber optics?’ ” says Taylor. “ ‘We barely know anything about real estate, let alone fiber.’ ” But Hynes had an idea to lay down a fiber-optic cable that ran directly from New York to Ashburn, Virginia, bypassing the big cities along the I-95 corridor where Verizon and others ran their cables. “I know this sounds weird, but I was like, ‘OK, that sounds like a great idea,’ ” Taylor says. “Somebody said we went from throwing copper to laying cable.”

Hynes served as the CEO, and Gracey, Taylor, and Dahlheimer all took positions at the company as well. But Taylor admits they didn’t fully understand just how much capital they’d have to raise to get the operation off the ground or the challenges they were going to face, since laying down fiber-optic lines, or hanging them from poles, requires government approval in whatever jurisdiction they’re going through. “I think there were 192 meetings in the state of New Jersey alone,” he says. “This is not for the faint of heart.”

Hynes stepped down as the CEO of United Fiber and Data in 2019 after he was charged with a litany of crimes related to his ex-girlfriend. The next year, he was sued by the company’s new heads and accused of a “pattern of unlawful conduct” that included stealing millions from the company to “fund a lifestyle that he otherwise could not afford.” Taylor was also named in the suit, accused of “breaching his fiduciary duties” and “self-dealing.” (The lawsuit was settled out of court in 2022.) In 2021, the Pennsylvania State Police announced that they were investigating a reported theft of more than $3.82 million from United Fiber and Data. That matter is still pending, and Hynes has denied any financial misconduct at UFD.

Shinn was still fronting Live while they were working on these projects, though he had no direct involvement beyond an investment of $250,000 that he ultimately got back. “They opened a countless amount of businesses, but it was literally a Ponzi scheme,” the singer alleges. “They’d take money from one to pay for the other … and they were able to get meetings because they were the guys from Live. That’s what got them in the door. They used that all the time.”

From Shinn’s vantage point, Hynes and Taylor were both complicit in the alleged financial misdeeds. “There was never anything Taylor didn’t know about when it came to Live,” he says. “He was the guy in the band that seemed to be in charge, and had all the numbers. I can’t imagine in a million years he didn’t know what was going on. That said, I don’t think that Bill Hynes is innocent either. And I do think that Bill is the dirtier of the two. He belongs in jail.”

Taylor, who says he is cooperating with a joint state police/FBI task force that is investigating United Fiber and Data, swears that he was unaware of any financial misdeeds at the time. “Anyone that might doubt my position should know that there were very sophisticated fiduciaries that he fooled as well,” he says. “I’m talking about outside accountants, outside auditors, inside CFOs, inside legal counsel, inside CPAs. We were all manipulated. I’m a guitar player. Call me unsophisticated.” (The FBI would neither confirm nor deny the existence of an investigation.)

Looking back now, Taylor wishes he’d paid more attention to the signals that things didn’t seem right with Hynes — in particular, the relationship with his accuser, who Taylor knew from her time working in the office. “I have deep regrets that I wasn’t more attuned to their relationship,” he says. “I was touring in a rock band, and it wasn’t like I was in the office every day.” Later, he was shown visual evidence from the alleged attack in Fiji that shocked him: “I saw photographs of the victim’s bruised face, her bloodied collarbone. Those images will never leave my mind. You can see thumb marks on her neck where she was choked. That’s not the kind of human being that I’m going to forgive.”

But like any good con artist, Taylor says, Hynes was very likable when he wanted to be. “If Bill wants you to like him, he’s extremely bubbly, gregarious, and generous,” says Taylor. “There’s some element in him that feels trustworthy. The very worst feeling that I’ve had this entire time is where I have dreams where I’m still with Bill and I’m having fun.”

TAYLOR AND I arrive at Bulls Head Public House to grab lunch. We don’t make it two steps into the place before Taylor bumps into an old friend from childhood at the bar. They embrace, and the friend tells the bartender to put our entire order on his tab. Taylor isn’t broke to the point where he can’t afford his own bison burger, but he’s grateful for the love. It’s one reason he’s stayed in Lancaster his whole life when most rock stars would have split for L.A. or New York after getting their first royalty check.

“I didn’t want to raise my kid in Los Angeles,” he says. “I wanted to raise my kid in an environment similar to where I grew up and that I understand. I’m as blue-collar as it gets. These are my people.”

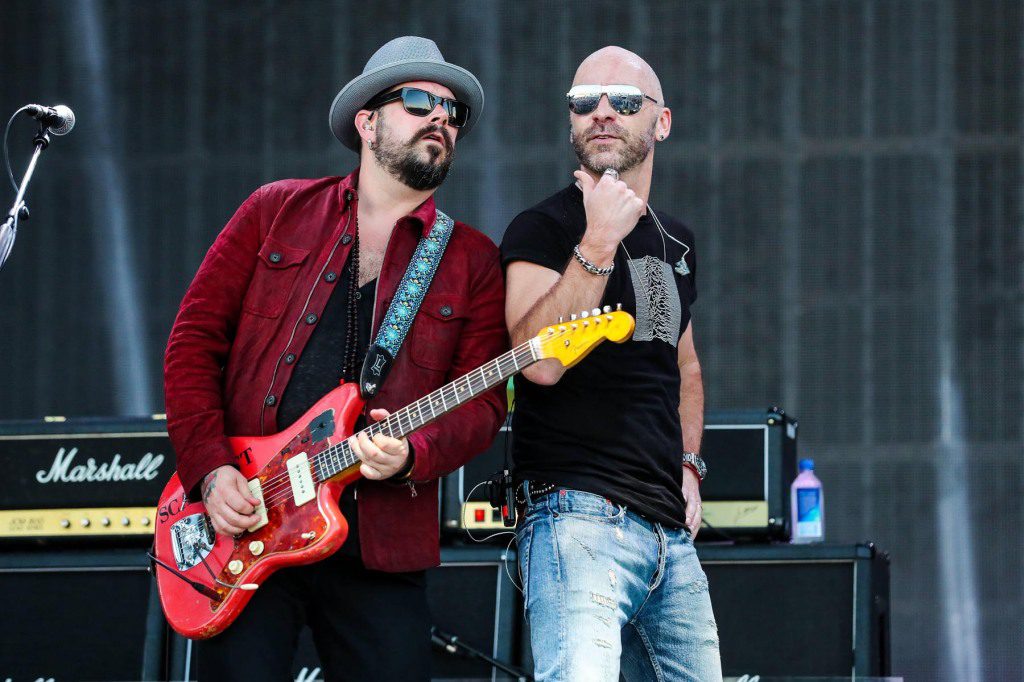

Taylor and Kowalczyk onstage in 2019.

ANDY MARTIN JR./ZUMA WIRE/ALAMY

When we sit down to eat, he explains how Live managed to reassemble their broken pieces in 2016 and get back on the road with Kowalczyk for a lucrative series of reunion shows. The band used to split the tour revenue four ways evenly, but Kowalczyk was enticed to rejoin them by an offer to up his share to 40 percent; Taylor, meanwhile, increased his own share to 30 percent, with just 15 percent each going to Dahlheimer and Gracey. “I don’t really know how to answer this,” he says when I ask why he took twice as much as his two bandmates. “I think it just reflects the historical truth of the band.”

That’s not how Gracey saw it. “Without Patrick and I knowing, Chad Taylor unilaterally negotiated with Ed,” the drummer complains when we speak. “Patrick and I were left with crumbs. That pissed me off from day one. It soiled the reunion.”

This is just one of the sometimes-outlandish accusations Gracey makes against his former best friend. “There was an inappropriate relationship between my now ex-wife and Chad Taylor,” the drummer claims. “He denies it, but I’ve confirmed it a few different ways.” Bill Hynes, too, claims Gracey’s ex-wife told him about this alleged affair. “That’s just despicable,” he says. “That’s the bro code.” (Taylor maintains that it is “categorically false” that he had sex with Gracey’s ex-wife — and she says the same, writing in an email, “I did not sleep with Chad Taylor and I have never spoken to Bill Hynes about any of this.”)

Or take the incident at the 2013 Grand Prix in Baltimore, in which Gracey and Hynes claim that Taylor punched Dahlheimer’s wife, Jacqueline, in the face. “He laid her out,” says Hynes. “He’s an abusive person.”

“That is absolutely, categorically untrue,” replies Taylor. “It’s just nonsense.”

Jacqueline Dahlheimer backs him up. “Bill Hynes is flat-out lying. This man is a predator and a master manipulator. I was never ‘knocked out’ by anyone in a bar. I was jabbed in the arm almost 10 years ago during an argument with Chad Taylor. None of the people commenting were present. My husband and I took this incident seriously and held Chad accountable. This private conflict which has since been resolved is being sensationalized to manipulate.”

(Patrick Dahlheimer declined to be interviewed for this article, but he did email us this statement: “We regret allowing Bill Hynes into our professional and private lives. Our family is working diligently to remove him and move on.”)

In spite of the hurt feelings over the money split, and the drama surrounding the business ventures with Hynes, the reunited Live stayed on the road between 2017 and early 2020, when they were sidelined by the pandemic. When live music came back in late 2021, Kowalczyk disengaged himself from the three others. He started posting cryptic comments to fans online, suggesting Live were only a band “in name” and adding: “Interpret ‘the reunion’ however you’d like … but I’m not in anyone’s ‘band.’ ”

“I hate social media,” Taylor says. “But Patrick wrote to me: ‘Ed is saying some weird stuff online.’ ”

And then in June 2022, in response to a fan question on Instagram, Kowalczyk took it a step further. “The three other original members are not speaking to each other — and I am stuck in the middle,” he wrote, “and if I try to go solo, there is a good chance they will sue me again — so I have to do what’s best for me and my family and try to stay out of litigation by not performing in public at all.”

When I ask Taylor about Kowalczyk’s sudden change in attitude, Taylor says at first he has no idea what prompted it. But then he thinks more about it. He does have a suspicion. “My theory is that Chad Gracey and Bill Hynes influenced him,” he says. “I think they picked the scabs off the old wounds, specifically the [band name] lawsuit.”

Gracey, again, has his own take. “I talked to Ed,” he says. “He said, ‘If you guys are going to be adversarial, I don’t want you onstage, and I just don’t want to deal with the drama.’ And Ed, to his credit, doesn’t have anything to do with this. He just wants to go play with Live, which he should be able to.”

Even though Taylor claims Kowalczyk has no legal means to fire him from Live, the guitarist also can’t force Kowalczyk to play shows with him. That’s why they worked out the legal arrangement that put Live back on the road with replacement musicians, and a portion of the proceeds going to Kowalczyk’s former bandmates. “Ed had management and our entertainment lawyer reach out,” Taylor says. “And by this point I just figured, ‘Well, clearly, at least at this moment, these are not my people, so we got to figure out a way to make it work.’ So that’s what we did. We worked out a deal.”

TAYLOR AND I head out of the restaurant and toward downtown Lancaster. This is where Live moved in the early days of the band, and there are memories on nearly every corner. Taylor points out the former location of a club where they opened up for the Pixies in 1990, and the building where they lived a few years later when they wrote Throwing Copper. “I feel like I used to know every person in Lancaster,” he sighs. “The town has grown so much.”

We park and walk into Redeux Vintage, an upscale vintage clothing store where a Billy Joel T-shirt from the Storm Front tour will set you back $75. In the early Nineties, this was Live’s rehearsal space. He points to a corner. “Ed wrote ‘Lightning Crashes’ right here,” he says. “And I wrote ‘Dam at Otter Creek’ right over there. It all happened right in this space.”

But this was a lifetime ago, back when the four working-class kids from York had the same dream and assumed they’d always be best friends. As the sun starts to set over the town, there’s so much that’s still unsettled. Hynes has yet to be charged for any of the alleged financial misdeeds related to UFD that the task force is apparently investigating, but Taylor and his legal team hope that’s coming any day. Taylor hopes this happens before Hynes is released from house arrest, because he’s terrified of what might happen if his former associate is back on the street.

Taylor’s last communication with Kowalczyk came in June 2022, when he emailed the singer and his team to refute an allegation that Taylor was planning to bring a new lawsuit against him.

“I want to be brutally clear because I do believe something is being manipulated or misinterpreted,” Taylor wrote. “Neither Patrick or I have ever threatened a lawsuit against Ed. Hand to God, strike me dead … Who is saying this? And why? Who would benefit if Live breaks apart? I want nothing more than to get on stage with our band. Period.”

He went on to tell the singer about his concerns regarding UFD’s finances. “Chad Gracey appears to continue to work with Bill Hynes, despite being warned that he could be placing himself in criminal jeopardy,” Taylor wrote. “Ed, more importantly, someone is playing heavily with your past emotions. That is not me, and it is not Patrick.”

The response from Kowalczyk chilled him: “Bill Hynes is innocent until proven guilty.… Direct any communications for me to [my lawyer] from this point forward.”

Taylor says that Gracey — who’s planning to start a new business venture with Hynes whose details he won’t reveal — has fallen down a rabbit hole of far-right politics and conspiracy theories, including QAnon. Gracey doesn’t entirely deny this. “I voted for Donald Trump in 2020,” Gracey says. “And I had my conspiracy theories about Covid and vaccines and stuff like that, sure. I would look at the [Q] stuff, and I never took it seriously. But I look at all kinds of stuff. It’s kind of funny that he’s bringing this up.”

At the moment, Hynes is suing Taylor for nearly $500,000 that he claims to be owed via a promissory note. (Taylor says it wasn’t a “valid promissory note.”) It’s one of three lawsuits Taylor is currently facing; he claims all of them are being “coordinated” by Hynes. “The legal fees are extraordinary,” Taylor says. “They’re trying to inflict maximum damage.”

As for Hynes’ victim, she wants to put this ugly chapter of her life behind her forever, though she hopes that other women going through similar experiences can learn from her story. “My hope is that anyone in the same position that reads this remembers one thing: There is still hope, do not give up,” she says. “There is light and freedom and happiness at the end of this dark and terrifying tunnel. There are so many women who don’t survive, and you only hear their story after it’s too late. I know I am very lucky to be alive, but I should have spoken out and involved law enforcement sooner. I feared the retaliation that would come from telling the truth. Deciding to leave will always be an extremely difficult path to take, and it’s unimaginably scary to think about standing up to your abuser, but that decision is the single most important decision that you will ever make in your life.”

Taylor hopes to return to music soon. He’s beginning to imagine a solo album and tour, possibly with Dahlheimer, where he can play old and new songs, and tell some of the stories he’s built up over a life in rock. He hasn’t played a single concert since that private gig in the Dominican Republic back in early 2020, and he misses performing desperately.

Gracey holds out hope that Kowalczyk will invite him back into Live sometime later this year. In his mind, a reunion of the four original members is impossible. “I don’t ever want to play with Chad Taylor again,” he says. “The best way to deal with a narcissist is to not deal with him, so I don’t want to. Every time he opens his mouth, he’s either manipulating you, trying to control you, or bully you.”

Taylor, despite everything, hopes the band someday finds a way to come together. “My family will kill me for saying this,” he says. “But I’d do a show with all the boys tomorrow. I love them — even Gracey and all his screwed-up shit. I love them, and I love the music we made.”