How a Sucker Punch Fueled the Rise of My Chemical Romance

In his new book, Sellout: The Major Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore (1994–2007), author Dan Ozzi examines the fraught decision that’s plagued some of the world’s greatest punk bands for decades: Whether or not to sign that record contract?

Sellout specifically examines the post-Nirvana goldrush as major labels descended on punk scenes with big promises and bigger stacks of money, sparking fierce debates among bands and fans over authenticity and independence. Based on a trove of original interviews and personal stories from band members and other crucial players, Ozzi examines how 11 groups — from Green Day and Blink-182 to At the Drive-In, Thursday, and Against Me! — grappled with the tension between punk’s core tenets and major label possibilities, and parses what success and failure looked like in this fraught realm.

In Chapter 11 of Sellout, Ozzi digs into the story of one of the era’s most successful and iconic groups, My Chemical Romance, and their celebrated second album (and major-label debut) 2004’s Three Cheers for Sweet Revenge. This excerpt, however, focuses on the band’s earliest days and their first album, 2002’s I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love, with Ozzi exploring how New Jersey’s unique musical landscape helped shape MCR’s sound, and how the unbridled potential of the internet was changing the nature of music discovery and the relationship between bands and fans.

Sellout: The Major Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore (1994–2007) will be published Tuesday, October 26th via Mariner Books at HarperCollins. Ozzi will appear at two upcoming events in support of the book: November 6th at Saint Vitus in Brooklyn and November 11th at Permanent Records Roadhouse in Los Angeles.

**

Sarah Lewitinn was sitting in the passenger seat of her mother’s Toyota Camry as it sped up the Palisades Parkway, frantically flipping through the pages of the book All You Need to Know About the Music Business as if she was cramming for a test. The twenty-one-year-old had talked herself into a gig managing My Chemical Romance, and as her mom gave her a lift to the band’s recording session at Nada Recording Studio, in upstate New York, it was dawning on her that she was in way over her head.

Lewitinn’s connection to the band had started three years earlier, on America Online, where she forged friendships with fellow music fans under the screen name Ultragrrrl. One day, she searched the member directory for Blur, Oasis, Radiohead, and Placebo, and up popped a profile for a user with the screen name MikeyRaygun. The account belonged to Mikey Way, a seventeen-year-old who told her that he worked at a supermarket corralling shopping carts during the day and slept on his parents’ couch at night. The two began exchanging music recommendations and flirty IMs, and she found him clever and funny. After a few months of messaging, she suggested they finally meet.

“We didn’t know how each other looked,” remembers Lewitinn. “I think he said that people had told him he looked like Leonardo DiCaprio. He sent me this blurry photo of half his face, and that was all I had to go off. The first time I met him was at the Starbucks outside the West Fourth Street station, in the West Village. But the person that was chatty on text and IM was completely different than the person I experienced in person. He was so painfully shy.”

Yet even through his timidity, Lewitinn could tell Way had ambition. “I remember going to Hot Topic and Virgin Megastore and all these places with Mikey, and he’d say, ‘I’m gonna be in those magazines one day, I’m gonna be on the covers, I’m gonna be on lunch boxes.’ He had a vision, from the moment I met him,” she says.

The two shared a teenage romance that lasted a few months. Way would take the PATH train into Manhattan and Lewitinn would ride the bus from her parents’ house in Tenafly, New Jersey. “We made out on every street corner in New York,” she says. The long make-out sessions were Lewitinn’s way of distracting herself from the fact that the boy she really wanted to be talking to was the outgoing MikeyRaygun. “Also,” she adds, “he was a great kisser.”

Once Lewitinn finally accepted that she was never going to get the charming online version of Way to come to life, she ended their fling, but was adamant that they stay friends. She didn’t hear much from him over the next couple of years as she began working her way into the music industry, but one night in the fall of 2001, she was sitting in her bedroom in her parents’ house when a message from MikeyRaygun popped up on her computer screen.

“He reached out to me and said, ‘I’m starting a band with my brother. You’re not gonna like it, it’s not your thing, but I’m really excited,’ ” she remembers. Lewitinn braced herself for songs that emulated the music she knew Way loved — “quasi-sci-fi, futuristic Brit-pop bullshit,” as she puts it. But when he sent her two mp3s, “Skylines and Turnstiles” and “Cubicles,” neither sounded anything like what she was expecting. “He was right that it was not something I’d listen to, but it was fucking great. It was this visceral thing I couldn’t even put my finger on. Just so much energy, so much excitement, so much thoughtfulness, and it grabbed me right away.”

Way bragged that they were working on an album they’d convinced Geoff Rickly to produce. “I knew who Geoff was because anyone that worked in the music industry knew who Thursday was at that point. They were poised to be the next Nirvana,” Lewitinn says. She begged Way to let her manage the band and, after talking it over with the rest of the guys, he agreed. She didn’t have any real managerial experience, but, she says, “I just knew I could fucking kill it.” It also didn’t hurt that she was willing to work for free.

My Chemical Romance got themselves booked on their first show in October 2001, at an Elks lodge in Ewing, New Jersey, opening for Pencey Prep, a brash hardcore band fronted by their friend Frank Iero, and Iero’s cousin’s band, Mild 75. The members of My Chem were so nervous about their first public performance that they downed a case of beers beforehand to calm their nerves. Once they were full of liquid courage, they sized up the room of about forty people and jumped into “Skylines and Turnstiles.” After rushing their way through it, they surveyed the crowd to find that, as far as they could tell, people actually liked them. They loved them, in fact.

“The room felt electric,” recalls Iero. “I remember standing on a chair at the merch table in the back and watching them play. They were all drunk, but it was still incredible. It felt like it could fall off the rails at any moment, but somehow it stayed together. They might have played for twenty minutes. There was a Smiths cover in there — ‘Jack the Ripper.’ If they played eight songs, that would be a lot. But I remember being like, ‘Holy shit, there’s something really special here.’ And everyone knew it. Everyone knew it.”

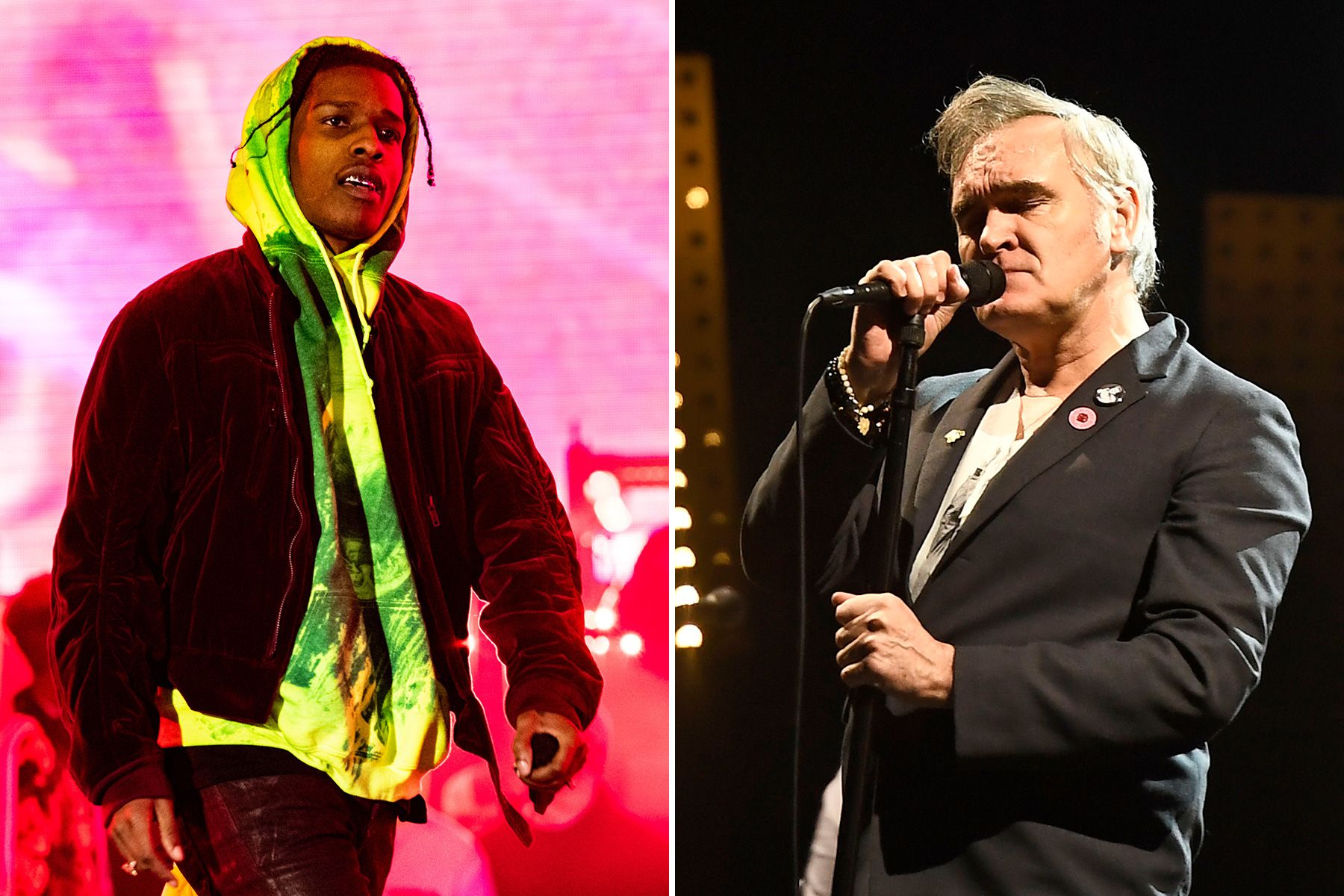

While most of the band stood with their feet firmly planted like cement blocks and dutifully ran through their songs, Gerard Way was already working the room like a veteran frontman, shedding his bashfulness the second he got the microphone in his hands. There was no stage, so he paced back and forth, claiming as much floor space as possible. His live persona took a little inspiration from his influences — the pained emotional delivery of Geoff Rickly, the operatic metal grandiosity of Iron Maiden’s Bruce Dickinson, the pompous swagger of Morrissey, and, like any good product of New Jersey, the ghoulish brooding of the Misfits’ Glenn Danzig.

Way wore a homemade shirt that read thank you for the venom, a phrase he’d coined that would eventually become the title of one of the band’s songs. “We used to have this joke where you can’t wear your own band’s shirt unless you were Iron Maiden,” says Saavedra. “And those kids were wearing their own shirts immediately. They were so confident that they were gonna be like Iron Maiden.”

“Gerard, especially, exuded a confidence of being whoever the fuck he wanted to be and didn’t give a shit,” says Iero, “which is weird, because offstage he was very introverted and self-conscious. But when he got up there, that unlocked something.” Iero made a point of seeing My Chem whenever they played from then on and considered himself their number one fan. He became part of the band’s small cadre of supportive friends, family, and girlfriends who reliably turned up to every show at Legion halls, VFWs, and small clubs throughout the tri-state area.

“They handed out a demo, and it had Mikey’s email address on the CD-Rs,” Iero remembers. “There was something special about those songs. I’d play them over and over again and say, ‘How is this so good? These kids came out of nowhere to put these three songs together and they’re fucking incredible.’ It was unlike anything else going on at the time. It was a bit alien in its voicings. There was almost a classical influence that Ray had. His chord progressions were off the wall. And of course Gerard’s singing just set it apart.”

After getting eleven local shows under their belt, My Chemical Romance decided that there was something lacking in their sound. Toro was a skilled guitarist, but there was a limit to how much he could pull off alone. Adding a second axman could help the band beef up their tone, they thought. Plus, having another member who wasn’t so stage-shy might inject more energy into their live show.

At the suggestion of Rickly, they considered Iero. It was the perfect time to poach him, since Pencey Prep was winding down, clocking in their final show that year at CBGB. Iero already knew My Chem’s songs and also had a chaotic and unpredictable stage presence that took inspiration from his favorite punk band, Black Flag.

At first, Iero felt uncomfortable with the idea of joining a new project that didn’t include his Pencey Prep pals, with whom he’d played music since high school. But the allure of My Chemical Romance was too undeniable to pass up. “Somehow, in some way, we all knew that My Chem was gonna do something important,” he says. “But I felt weird about leaving my friends behind; I felt bad about it. At the same time, My Chem was my favorite band in the entire world. It’s like being a kid and having your favorite band ask you to be in it. It’s a no-brainer.”

“It was a four-piece and then Frankie came in,” says Lewitinn. “He was a fucking star, and I was glad he was in the band, because all eyes were on Gerard, but someone needed to alleviate him at some point. It wasn’t gonna be Mikey, because he was scared shitless to be onstage. Their drummer, Otter, was fine, but he was like a bro, not really commanding any presence. Ray was technically wonderful, but he wasn’t commanding the audience in the same way that Frankie could.”

Not only did Iero help thicken the band’s rhythm section; his occasional shrieking backup vocals added a spazzy hardcore element to My Chemical Romance that borrowed from the screamo sounds commonly heard in New Brunswick basements. He became the band’s wildcard, always leaping off the bass drum or writhing around on the floor.

As soon as Iero joined, the newly minted quintet trekked up to Nada Studios to get their debut album recorded. The band took to their first official studio experience like kids on Christmas. Nada was a small setup in the basement of engineer John Naclerio’s mother’s house. The ceilings were low, the rooms were cramped, and the recording booth was accessed through a laundry room. But the sight of real mixing boards and soundproofed walls made the band feel like professional rock stars.

“It was a home studio, but it might as well have been Electric Lady to them. Ray, especially, was like a little kid. He was so excited,” remembers Saavedra. “There were a few times when his legs were shaking and it was picking up on the recording. We were like, ‘Dude, you gotta stand still!’ And he was like, ‘All right, I’m sorry! I’m just so excited!’ ”

With only enough budget to cover two weeks of recording time, the band got to work rushing through their debut LP, I Brought You My Bullets, You Brought Me Your Love. The members’ wide array of musical tastes produced eleven songs that were scattered and uneven, but that was part of their charm. “Early Sunsets Over Monroeville” was a five-minute homage to nineties emo in the style of the Promise Ring. “This Is the Best Day Ever,” with its galloping punk beat, took a cue from revered Jersey veterans Lifetime. The most structurally disparate track, “Honey, This Mirror Isn’t Big Enough for the Two of Us,” shifted abruptly between styles like a car with a broken transmission. Pure metal-worship riffs dissolved into melodic verses randomly peppered with abrasive screaming, throwing the kitchen sink of influences at the listener.

The band’s amateur energy produced plenty of serendipitous compositions, but when Lewitinn was dropped off by her mother, she was faced with her first managerial crisis: her band was having trouble getting decent vocal takes out of their singer. “Alex was like, ‘We can’t get Gerard to record. There’s something wrong with his ears and he’s not feeling well. We need every day we can get, because we don’t have a lot of money,’ ” she remembers. “I’m fretting because I have zero dollars. I can’t pay for more studio time.”

“He had a terrible earache and this pain in his head,” Saavedra says. “We couldn’t figure out what was going on with him. The dude was really in major pain, but we needed to finish this fucking record. We kept bringing him to the ER and they were like, ‘There’s nothing wrong with you!’ ”

“So I go out to the car and ask my mom what to do,” Lewitinn remembers. “She was like, ‘Get Gerard in the car right now. We’re going to the hospital!’ We get to the hospital and she’s telling [the staff], ‘You’re taking him right now! He’s recording a record, he needs to have this done, you have to see him right this second!’ He ended up needing a root canal or some dental work, but she insisted on waiting with him. She stayed with him the whole time. After that, my fifty-five-year-old Egyptian mother was in love with Gerard.”

Way’s swollen jaw did lead to one bit of studio magic. As the singer’s pain grew stronger after the procedure, vocal takes started coming out flat and lacking in emotion. “I just wasn’t happy with what he was doing. Neither was Alex,” says Rickly. “Alex stole his pain meds and told him he couldn’t have any more and needed to record.”

After depriving Way of his Vicodin and giving him several unsuccessful pep talks, Saavedra tried one more motivational trick. “I punched him in the face,” he says. “I thought I knocked him out at first. It shocked the shit out of him. In hindsight, it was very jockish, but at the time it made sense. I think the masochist in him really enjoyed it. It definitely hurt, but it amped him up. It was a different kind of pain. He slayed that vocal take right after that.”

Saavedra’s fist not only slugged better performances out of Way; it also pounded a notion into the singer’s head that would become an integral part of how My Chemical Romance operated. Sometimes, Way learned, he’d need to embrace the pain.

Although Lewitinn was young and inexperienced, her hustle made her a good manager for a new band to have in its corner. She networked her way through three shows a night in Manhattan and spent her days spreading music gossip online. As soon as she got hired by the band, the hyperconnected manager sang My Chemical Romance’s praises from her keyboard. She emailed their demo songs to her friend who did A&R at Atlantic Records and to her friends who were writers at SPIN and NME; she posted about the band on Thursday’s message board and fired off IMs to tastemakers. The buzz she stirred up was enough to get the band written up in Hits Daily Double, a hot spot for A&R chatter. The band’s songs bounced around the music industry after that, and before she knew it, she no longer had to tell anyone about My Chemical Romance. People were now coming to her.

“All these label people were calling me all of a sudden,” she says. “I suddenly had people flying in to New York to see the band play at the Loop Lounge. Rob Stevenson, at Island Def Jam, was interested in signing them because his rival at Island had signed Thursday, so he wanted to have My Chem. It was moving superfast. It went from zero to 120 overnight.”

It wasn’t just industry insiders who were discovering the band through the internet. The band members, particularly the Sidekick-addicted Mikey Way, had a sixth sense for using the web to their advantage, and were corralling new fans wherever they gathered online. The band’s name got around on local message boards like TheNJScene and on social networking sites like Friendster, Live- Journal, and the alt-culture favorite Makeoutclub. Hype around My Chemical Romance spread the old-fashioned way — by word of mouth — but thanks to the facility of the internet, it was happening at a rapid pace.

“Mikey lived online,” says Lewitinn. “The internet was fucking huge for them. That was how people found out about them. They had their EP on their website, where people could download the songs or snippets. Any opportunity we had to spread their music digitally, we would do it. I was selling merch at their shows and giving people their website, making sure kids were signing up for mailing lists. I’d sit there and type in everyone’s email and send out newsletter updates.”

By the time Eyeball Records released I Brought You My Bullets, on July 23, 2002, it seemed as though My Chemical Romance was already on the lips of every record company. “All these labels were hitting me up, and I was taking the band out for meetings. It was all happening so fast and effortlessly,” Lewitinn remembers.

“Finally one day the band asked me to meet up with them,” she continues. “They were like, ‘We love you, we think you’re amazing, we’re thankful for all the help you’ve given us, but we feel like you’re pushing us too far. It’s too much, too soon. You’re trying to give us the big time and we’re not ready for the big time yet. We want to be a punk band, we want to build up, we don’t want to take the fast route.’ That’s the best way to be fired: being told you’re doing too good of a job. I was so surprised, but I couldn’t be bitter about it. I had to respect their vision and their goals. Similar to my breakup with Mikey, I wanted to continue helping this band any way I could. So when I got a job at SPIN, any opportunity I had to write them up, I was taking it.”

“At the time, I remember thinking Sarah wasn’t the best manager for them,” says Rickly. “But in retrospect, she had a big influence on how they thought about what was going on. She pushed them to embrace the androgynous or feminine aspects of the band. So to minimize her contribution to their savviness is a huge mistake.”

But even after Lewitinn was let go, opportunities continued to fall into the band’s laps. In August, shortly after Bullets was released, they were contacted with a last-minute offer to fill in for Coheed and Cambria, who had to drop off a date in nearby Allentown, Pennsylvania, opening for the Juliana Theory and Jimmy Eat World. But it wasn’t at a midsize club or hall; Jimmy Eat World could now fill a sprawling fairground, thanks to a wild breakout year. After two failed releases that had gotten them dropped from Capitol Records, the Arizonans self-funded the production of their follow-up, Bleed American. It was a record so undeniably accessible that labels started sniffing around again. “Word of mouth had gotten around that the material was strong,” says drummer Zach Lind. “Hollywood Records was really interested, MCA wanted it, Sire wanted it, Atlantic wanted it. Even Capitol got interested again. It was total FOMO.” They were pursued so intensely that eventually producer Mark Trombino had to start locking the door of their studio. The winner of the bidding war, DreamWorks, had its investment immediately pay off when the band’s single “The Middle” found success and broke into Top 40 radio thanks to its sugary chorus. The song became a top-five Billboard hit and, in the month the band was set to play Allentown, Bleed American went platinum.

“That was [My Chem’s] first break. Jimmy Eat World was huge at the time,” says Saavedra. My Chemical Romance realized they were in over their heads as soon as they pulled into the parking lot and saw how ridiculous their cheap rental van looked alongside the other acts’ massive buses. “I remember the stage manager was like, ‘Do you have your stage plot?’ And the guys were like, ‘Yeah, hang on.’ Then they went back and were like, ‘Uh, sorry . . . what is that?’ They were a baby band. They’d never played on a stage like that. They were playing little halls and Maxwell’s, in Hoboken. They didn’t know anything about stage plots.”

If My Chemical Romance had been skittish about playing in front of a few dozen people at a New Jersey Elks lodge, they were scared out of their minds when they looked out onto the thousands of people gathered at the Allentown Fairgrounds. But even though he was petrified, Gerard Way became another person when he looked out onto the faces in front of him, like a man possessed. The massive stage didn’t overwhelm him; it actually fueled him.

“Me and my girlfriends watched from side stage and we were freaking the fuck out,” says Lewitinn. “We’d only seen them on tiny little stages — rec centers in Jersey. I’d seen them play CB’s once. But I was finally seeing My Chem on a stage big enough for them.”

Iero was so nervous that he clenched his eyes shut through the first few minutes of the set. The band played “Headfirst for Halos,” whose mathy guitar intro, like something nicked from a Rush song, was built to rock arenas and stadiums. Midway through, Iero looked up to find that a sea of people were jumping up and down to the beat. “I remember we got the crowd to bounce,” he says. “And we all looked at each other like, ‘Holy shit, there are thousands of people here. This is crazy!’ It was the biggest show we’d ever played, it was the best response we’d ever gotten, it was the best feeling we’d ever had.”

My Chemical Romance had gotten their first taste of rock stardom that night, and they were hooked. From then on, Iero says, the band was committed to doing whatever was necessary to make that feeling happen every night, no matter how much time, work, and faith it took to get there.

“I signed my first autograph at that show,” Iero says. “I felt re- ally weird about it. I remember thinking, ‘I shouldn’t be signing this. I’m not even supposed to be here.’ And my friend Eddie said, ‘Think about it: if you were this kid, you’d want someone to sign this for you.’ So I wrote my name and the kid was like, ‘Can you please sign more than that?’ So I wrote, ‘Keep the faith.’”

Excerpted from Sellout: The Major-Label Feeding Frenzy That Swept Punk, Emo, and Hardcore (1994–2007). Copyright © 2021 by Daniel Ozzi. Published and reprinted by permission of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins LLC. All rights reserved.