Hit Songwriters Tell All, from Thieving Artists to Grammy Snubs

The recording industry may slowly be waking up to the fact that some of its most important creators are wildly undervalued — one sign is the first-ever Songwriter of the Year Grammy, which Tobias Jesso, Jr. recently won for his behind-the-scenes work with Adele, Harry Styles, FKA Twigs, Omar Apollo, and others. But as our recent report on the state of the songwriting business emphasizes, the model for compensating writers is deeply broken. The people we spoke with revealed that in a streaming-dominated world, writing a great song for a major artist isn’t enough to earn a living anymore: Only radio hits (and TV and advertising syncs) stand any chance of bringing in real money. Here, six prominent songwriters weigh in on the trials of surviving in a brutal business.

Emily Warren has written for Dua Lipa, Khalid, and Lizzo, among many others, and released a solo album, Quiet Your Mind, in 2018.

I co-wrote “Don’t Let me Down” for the Chainsmokers, which won a [Best Dance Recording] Grammy, and not only was I not invited to the Grammys, but I didn’t get a trophy. I had to pay 80 bucks for a piece of paper that symbolized the award. That was just unfortunate, because the engineer got an award and the featured artists got an award — everyone but the people who wrote it got trophies. It’s hard to not go home after that and be like, “I’m worthless in this equation.” And if you’re worthless in the equation, no part of you is going to be like, “I’m gonna put my foot down now and insist that I’m properly compensated.” I think songwriters need to feel like they have enough value to respect themselves when it comes to actually doing business.

Warren “Oak” Felder is a producer and songwriter who’s written for Nicki Minaj, Alessia Cara, Usher, Chris Brown, and Jennifer Lopez, among others.

Imagine if I wanted to get a house built, right? I’d have to hire contractors to do a multitude of things.. Now, imagine if I told them “Listen, come build my house. I’m not going to pay you unless the house becomes famous.” Contractors would be like, “OK, you’re not getting a house built today, buddy.” That’s essentially the state of the music industry right now for songwriters. And I think that it’s unfair that they have to deal with that inequity.

Again, unless you get a huge single, you’re not necessarily getting paid. So songwriters know that if they’re writing for an artist, they need to do something that is 100 percent commercially viable. But what does that do to the art itself? It means that whatever the current commercial trend is for hit records, the person walking into the room is going to make that. And so it strips us of the creative freedom that might otherwise create something unique or trendsetting. If you walk into a room not thinking, “I have to make a commercial hit,” you might end up changing the face of music with something that doesn’t sound like anything else. A good example is “Human Nature” by Michael Jackson. It’s not necessarily a song that anybody during that process thought was a hit record.

Instead, songwriters walk into the room, and they go, “OK, what are the hits that are out right now,” and they grab the vibe from those hits. I love the fact that there’s so much music out now. But I have to acknowledge that a lot of the music that does get released today sort of washes into the gray. It all sort of becomes the same thing over and over and over and over.

There are artists who will work with songwriters, and then at the end of the process, they’ll say, “OK, now you need to give me 20 percent of the record” — even though they didn’t necessarily write the song. I try as hard as I can to not be in a room with those types of artists, and more and more songwriters are doing the same.

I’ll tell a story, and I won’t name names. There’s an artist whose career started off very prominently. And this individual featured on a lot of different songs, and blew up, like, overnight, and then this individual ended up getting huge, huge hit records. But unfortunately, this artist had the habit of taking 15 percent. And in the style of music they made is one where people assume that the artists had to be a part of the writing for every song — but it wasn’t necessarily the case. So this artist ended up getting a reputation for mistreating a lot of songwriters. And a lot of songwriters and even producers opted to stop working with this artist and started focusing on a newer artist who was very similar. Today, I would argue that the first artist is struggling to maintain relevance and the artist that is replacing them is one of the biggest artists out right now. So literally, the creative base went from this person to that person, because of the way this person treated the creators around them.

Kevin Griffin is the frontman and songwriter for Better Than Ezra, and has co-written with artists from David Cook to Barenaked Ladies. His first book, The Greatest Song: Spark Creativity, Ignite Your Career, and Transform Your Life, is due in April.

As a songwriter, you used to be able to say, “Hey, man, I don’t need to produce. I’m just gonna be in that room, and I’m gonna bank on myself. If I get in there, I’m gonna write and be a part of a great song.” Now we’re like, “Oh, gosh, the odds of making any money on this song are so minuscule. So why am I doing it?” So what a lot of songwriters are doing, is when you’re in a session now with a TikToker or an independent artist, you’re like, “I need to have part of the master [recording] as well.” Because there’s a lot of money to be made on the master side. It’s a touchy subject, because for songwriters who are less successful, you don’t have that leverage. But what I hope is going to happen is, in the next three to five years, the paradigm will shift towards that as a songwriter — because right now the songwriter is getting left pretty much in the dust. And I don’t care how great of a producer you are, if you don’t have a great song, you don’t have anything.

As a veteran songwriter, I’m so happy that so many of my masters have reverted back to me — all the Ezra ones, we control. But just songwriting alone, it’s really tough going out there. I’m not complaining, though. This is just where we are now. I’m pivoting and I am doing [ad and TV-licensing-centered] sync projects and different things. And I’m an eternal optimist, because I saw the Nineties and the 2000s where it was “the end of the industry.” Now there’s just tons of money being made on the master side. OK, how do I weave my way into it? Unless you’re Green Day or Coldplay, some band that’s always been massive, you’ve just got to diversify. If you want to stay in this career, you need to have a lot of irons in the fire.

Al Sherrod Lambert has written for Janet Jackson, Pitbull, the Isley Brothers, Ariana Grande, and Brandy, among other big names.

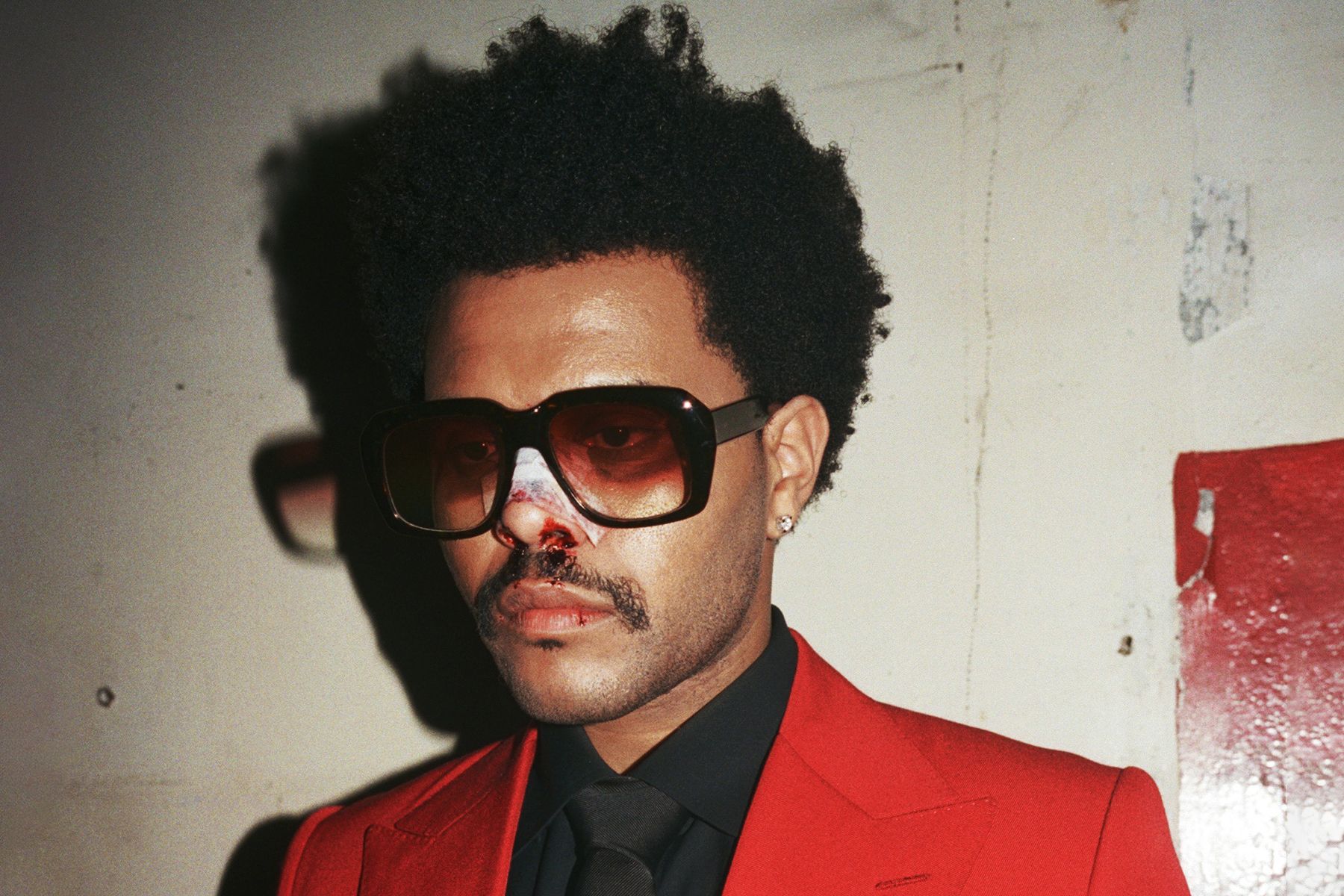

Steve Granitz/WireImage/Getty Images

Publishing companies have a role to play. My idea is that artists who just signed to a major publishing company should at least have the option of popping into that company’s healthcare program, because Obamacare can still be expensive. I think about my friend who’s from New Jersey as well, I went to college with him, Kyle Stewart. In 2014, we were nominated together for R&B Song of the Year [for “Without Me,” recorded by Fantasia, featuring Kelly Rowland & Missy Elliot].

The next year, Kyle died at 27 years old. He went to a hospital with chest pains, and they told him he was going to have to have some tests and asked if he had insurance. He did not have it, so he said, “I’ll go home and sleep it off. “And unfortunately, he didn’t make it, because he had a blood clot that he didn’t know about. But they might have caught it had he felt comfortable enough to just stay in the emergency room and let them do the tests. And he was signed to a major publishing company. So these are things that I think about.

Scott Harris has written extensively with Shawn Mendes as well as for Justin Bieber, Camilla Cabello, and more.

It’s definitely a moment where the song comes out and there’s, like, eight or nine writers in the credits, and I’m thinking to myself, “I wrote that in the room with three people, and now everybody thinks that all these people wrote the song, when they’ve changed a word or two, or they’ve added a guitar part.” On the split sheet, it’s all the same, you know?

What I’ve seen a lot more over the past year or two is, like, a loops person being involved or a player being involved. There’ll be someone in the room who just plays guitar or just plays piano and they’re not the producer. They’re not sitting behind the computer. And they’re most definitely part of the song-making process. It’s inspiring to have that person in the room — but it is another person in the room, and the more people, the less money you’re gonna make. So it does become a little bit of a numbers game.

Sam Hollander has written with Panic! At the Disco, Weezer, Gym Class Heroes, Katy Perry, One Direction, among many others. He recently wrote the entertaining memoir 21-Hit Wonder: Flopping My Way To The Top Of The Charts.

As a songwriter, the deck is stacked against you. You get into this and you want to believe that everything is possible, that you’ll ascend to the heights of all your heroes. And then suddenly, you’re in this dance, and it’s awful. It’s such a brutal game to navigate. It used to feel like every day I woke up, walked outside, and got hit by a cab, seven days a week for 15 years — and then I had to get up and actually go write a song. Because that’s what it was like. There are no layups in this.

My last real non-music day job was truly probably bouncing at the Bitter End, bouncing 70-year-old men in a folk club. And that was probably ’89-’90. I was able to hustle my way from gig to gig to gig, and I tried everything. I kept getting deals. Now, streaming has eradicated the middle class. And that’s the most heartbreaking part of it. Right now, it’s just it’s a feast or famine for songwriters.

When I first arrived in L.A. [in the ’00s], I noticed the shift to [multiple co-writers], and it was seismic right then and there. I’m not going to necessarily claim purist status by any stretch, but it still freaked me the fuck out. As I sort of began to get the lay of the land, I realized it really was akin to screenwriting to some extent. You know, if you’re writing a Fourth of July popcorn blockbuster, there’s gonna be a zillion punch-ups until they get it right.

Bur right now, there is no process. It’s absolute chaos. Records were made a certain way. Artists worked with different writers and then 10 songs made the record and one was the single. But now, some 16-year-old kid can put up some track they made last night as a joke with their friends, and that can get offered $3 million two days later. It’s another thing that makes it an absolute uphill battle right now for the working songwriter, because it’s impossible to permeate records of kids who are in their own closed collectives of just having fun and being young and doing their thing. Big tentpole artists are trying to compete with that 16-year-old kid who made the funny song last night.

At the end of the day, you know, I want to believe I was one of the more tenacious motherfuckers who’s ever done this. My first hit occurred when I was 35 years old. I stuck it out and I ate shit for so many years in the process, and the one thing I would say is I never repeated mistakes.

I don’t do songwriting camps. An A&R guy once said to me, “Don’t waste your time with that.” He said, “We bring a bunch of young writers there and they have a great time. All the songs suck, but usually there’s one or two that stand out. And then what we do is bring them to guys like you to rip them off.” The look of horror on my face. I’ll never be able to replicate it, dude.