Heavy Metal, Year One: The Inside Story of Black Sabbath's Groundbreaking Debut

Before the world recognized as heavy-metal forefathers, the band members wrote a song that gave them the chills.

“We knew instantly that ‘Black Sabbath’ was very different to what was around at the time,” guitarist says of the piece that gave the group its name.

“We always wanted to go heavier than any other band,” bassist says.

“I thought the song would be a flop, but I also thought it was brilliant,” drummer says. “I still think it’s brilliant.”

“When we played that song for the first time, the crowd went nuts,” Butler says.

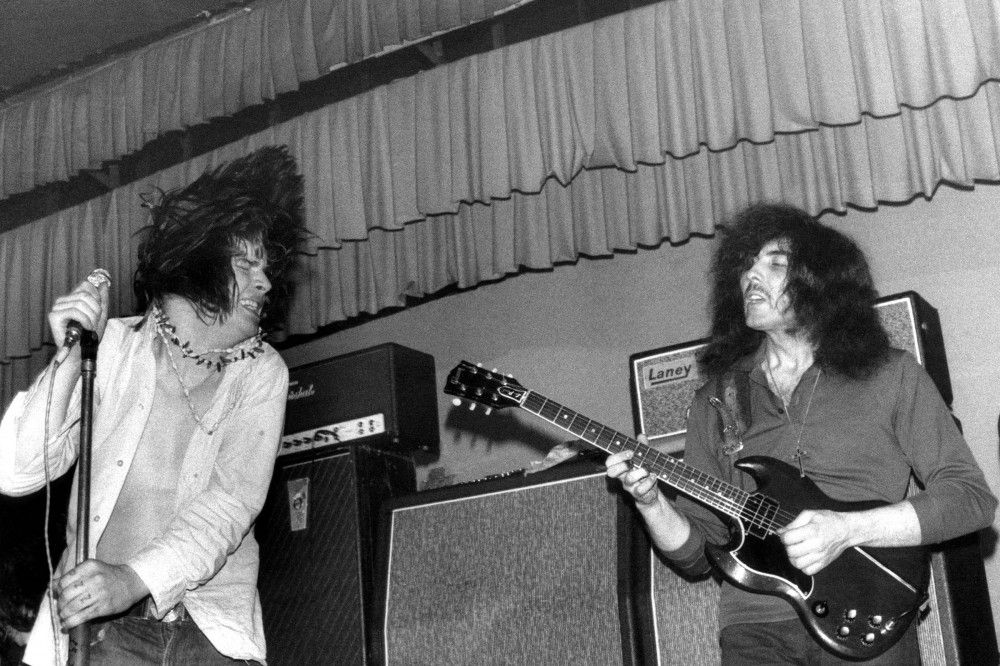

Half a century has passed since Black Sabbath first scared the bejesus out of rock fans with their eponymous anthem. The song opens with the sound of a powerful thunderstorm and ominous church chimes before crashing into its lumbering, iconic riff. The guitar chords lurch seismically, each one like a gut punch before quieting down just enough for to paint his own vivid portrait of fear — “What is this that stands before me/Figure in black which points at me?” It’s a scene so unnerving that he eventually pleads to the heavens, “Oh, no, NO, please God help me,” before the guitar riff and church bells come around again to strike him down. “Is this the end, my friend?” he wonders aloud. The six-minute horror vignette was spooky yet thrilling, and the song, “Black Sabbath,” would serve as the prototype for a genre poised to captivate the world.

Artists like Jimi Hendrix, Cream, and Led Zeppelin had spent the late Sixties edging into darker, denser terrain, but it was Black Sabbath who made heavy a way of life. When their debut album, Black Sabbath, hit U.K. record stores in February 1970 — on a Friday the 13th to capitalize on the album’s unsettling look and sound — it showed the world what “heavy” really meant. The album sleeve depicted a witchy-looking woman holding a black cat in a supernatural world, and the music inside delivered on the cover’s mysteriousness.

In between the LP’s stark, gothic, crushing riffs and dusky psychedelia, Osbourne detailed a date with the devil (“N.I.B.”), sang the praises of a benevolent sorcerer (“The Wizard”), and narrated more scenes of terror, like a “sleeping wall of remorse that] turns your body to a corpse” (“Behind the Wall of Sleep”). The U.S. edition of the album, which arrived that June, improved on the original release by swapping in a lightning bolt of a blues track about the evils of society (“Wicked World”) in favor of the cover song “Evil Woman.” On each opus, Iommi, Butler, and Ward summoned monoliths of sound, wrenching their riffs about with abandon. The record was dark, direct, and raw — a true original.

Now, with 50 years’ worth of hindsight, you can hear that the album represented the start of a new epoch. Without Black Sabbath, Metallica wouldn’t have had the blueprint to write “Enter Sandman.” Judas Priest might never have broken the law, Iron Maiden wouldn’t have run to the hills, and Slayer would have never reigned in blood. These bands might have existed (Judas Priest did exist at the time of Sabbath’s debut), but it’s hard to imagine that any of it would have sounded the same. The echoes of the macabre imagery, powerful guitar riffs, and athletic drumming on Black Sabbath haven’t just rippled through the music of bands like Slipknot, Rage Against the Machine, and Pantera; they’ve also made their way into punk, indie rock, and even hip-hop. Yet on its own, Black Sabbath still sounds unique. If a Martian were to land on Earth and ask, “What is ?” the best answer would be to play “Black Sabbath.”

But because so much music has drawn inspiration from Black Sabbath, it’s difficult to imagine how the band started, where its members came from, why they sounded so morbid. These days, the band’s status as the progenitors of heavy metal is practically undisputed. But a half-century ago, they were the furthest thing from legends, just four scrappy roughnecks from Birmingham, England, playing the blues. So to mark the 50-year anniversary of the group’s paradigm-shifting album, Black Sabbath’s members, collaborators, peers, admirers, and the acts they covered have all taken a moment to reflect here for a thorough accounting of how the group came to define the metal genre.

“There is no doubt in my mind that Sabbath invented what we know as the start of true and pure heavy metal,” Judas Priest frontman Rob Halford says. “Without them, the genre may never have come to be.”

The members of Black Sabbath were a group of fresh-faced young men when they first played together in the summer of 1968 in Birmingham, following stints in other bands. Butler was only 19, and the rest were all 20. They had each come from humble backgrounds and grown up in the Aston neighborhood of Birmingham (which Iommi has likened to Detroit); the guitarist and Osbourne had even attended the same school. Although nearly two decades had passed since the end of World War II, the city was still deep in the redevelopment that followed the years-long Birmingham Blitz. The area was thriving economically, with its industry rooted (funnily enough) in metalwork, such as motorcycles and jewelry, but it was still a dreary environment, especially for young men who felt like they had no future, which was the case for much of Black Sabbath.

“We were quite disheveled in terms of money, property, and prestige,” Ward recalls. “We didn’t have anything. When I listen to our first album now, I can hear the purity of the oneness of leaving all earthly things aside to come together and create something. It’s quite marvelous.”

Each of the band members had a rough go at early-adult life. Osbourne worked in a slaughterhouse and did jail time, Butler was an accountant, and Ward delivered coal. Meanwhile, Iommi’s job practically ended his livelihood. One day at the factory where he did welding, he was moved to an unfamiliar machine that lopped off the fingertips of his fretting hand. But he relearned the instrument — drawing inspiration from jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt, who also only had two functioning fingers — and soon got back to business.

Eventually, Iommi linked up with Ward in the bands the Rest and Mythology, the latter of whom played upbeat electric blues. Their set list, featured in a 1968 live recording, included a rousing rendition of folk singer Bonnie Dobson’s “Morning Dew” and a walloping take on Howlin’ Wolf’s “Spoonful.” Meanwhile, Butler was playing guitar in a psychedelic band called Rare Breed, whom he has compared to Sgt. Pepper’s and Syd Barrett–influenced bands like Art and Tomorrow. After their singer quit, Rare Breed found a new one by responding to a posting in a local musical-instruments shop that read, “Ozzy Zig Needs Gig.” Osbourne, who has said he has no idea where “Zig” came from, joined the group toward the end of its existence but never played a gig with them.

After both bands fell apart — Mythology got busted for smoking weed, which was enough of a setback to crumple a band at the time — the four musicians found each other through the “Ozzy Zig” ad, which Osbourne had left up, and formed a new band, creating the foundation for Black Sabbath. They called themselves the Polka Tulk Blues Band (“Polka Tulk” alluded to the brand of talcum powder Osbourne’s mom preferred), and they were originally a six-piece group with a bottleneck-slide-guitar player named Jimmy Phillips and a saxophone player named Alan Clark. Butler switched to bass since the group already had two guitarists. But after playing jammy blues at a couple of gigs in August 1968, Iommi decided it just wasn’t working out.

“It was awful,” Iommi says of the band in the Polka Tulk days. “It was a mishmash, like a jam. I don’t know if it was taken that seriously, with a sax player and a slide-guitar player.”

“I really liked that band,” Ward says. “I was having a good time. But we went up to Carlisle as a six-piece and came back as a four-piece.”

At the drummer’s suggestion, the group rechristened itself Earth, and continued playing electric blues, which was somewhat against the grain of the Birmingham scene at the time. To get a gig in one of the local clubs, you had to play pop, dance, or soul music. Butler remembers Earth at one point playing Eddie Floyd’s swaggering “Knock on Wood” at gigs; Ward recalls he and Iommi sharing a love of Wilson Pickett. Popular bands that played Birmingham around that time were the Idle Race, Jeff Lynne’s band before the Move and Electric Light Orchestra, and Free, who had a big hit in 1970 with “All Right Now” and whose singer, Paul Rodgers, became one of the Seventies’ great frontmen in Bad Company.

But Earth’s members felt a deeper connection to the blues scene that London had birthed earlier in the Sixties, and the American artists who inspired it. One of the best places to see live blues locally at the time was “Henry’s Blueshouse,” which wasn’t a standalone venue, but a weekly live-music night held at the Birmingham pub the Crown. Jim Simpson, a trumpeter who played with a Birmingham jazz, soul, and prog-rock group called Locomotive, had started renting out the space, which could hold 180 people, on Tuesdays (“Bluesdays!”) to prop up local and touring acts. As Simpson wrote in his recently released book, Don’t Worry ‘Bout the Bear — which gives his perspective on Sabbath’s earliest days — patrons could buy an annual subscription to the series for only a shilling (five pence). The two charter members were “John Michael Osbourne” and “Anthony Frank Iommi.”

They quickly befriended Simpson and told him about their band and said they’d love a chance to play Henry’s. Eventually, Simpson gave them the “intermission” spot during a gig by Ten Years After, a hard-rocking electric-blues group that went on to stun Woodstock audiences in ’69 with frontman Alvin Lee’s wild solos on “I’m Going Home” and scored a somber pop hit in the Seventies with “I’d Love to Change the World.” “They were really very good indeed,” Simpson remembers of Earth. “We gave them more intermission spots, and they visibly built a following, right from the beginning. We gave them a headline spot, and they sold it out.”

“They were a generic blues band,” Ten Years After’s then-bassist, Leo Lyons, recalls of Earth in the early days. “They were playing Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker kind of stuff. They hadn’t transitioned into what I guess you could say became metal. We thought they were pretty good.”

Before long, things were going so well that the members of Earth asked Simpson to manage them. When Simpson looks back at this early period, what stands out to him is how unique each of their personalities were at the time. “Tony always had dignity,” he says. “He wasn’t easy to argue with, didn’t back down easily. But he would see logic if it was presented to him properly. Geezer would always find something amusing in life that nobody else quite saw. He’d make pretty clever, pithy side remarks. Bill was very quiet, introverted. All he wanted to do was play music. I spent the most time with Ozzy. He was insecure, and he needed an arm around his shoulders and to be comfortable — ‘It’ll be all right, don’t worry’ — because he was worried around his performances. He was very sensitive, very curious. But he gave everything onstage. He left nothing behind.”

“When I think about Oz, when he was a teenager, I’m just reminded of what an excellent blues voice he had,” Ward says. “He had a large voice. When we did the Aynsley Dunbar song ‘Warning’ and ‘Black Sabbath,’ his voice is so right. It’s really round, and it has that pain from within in his voice.”

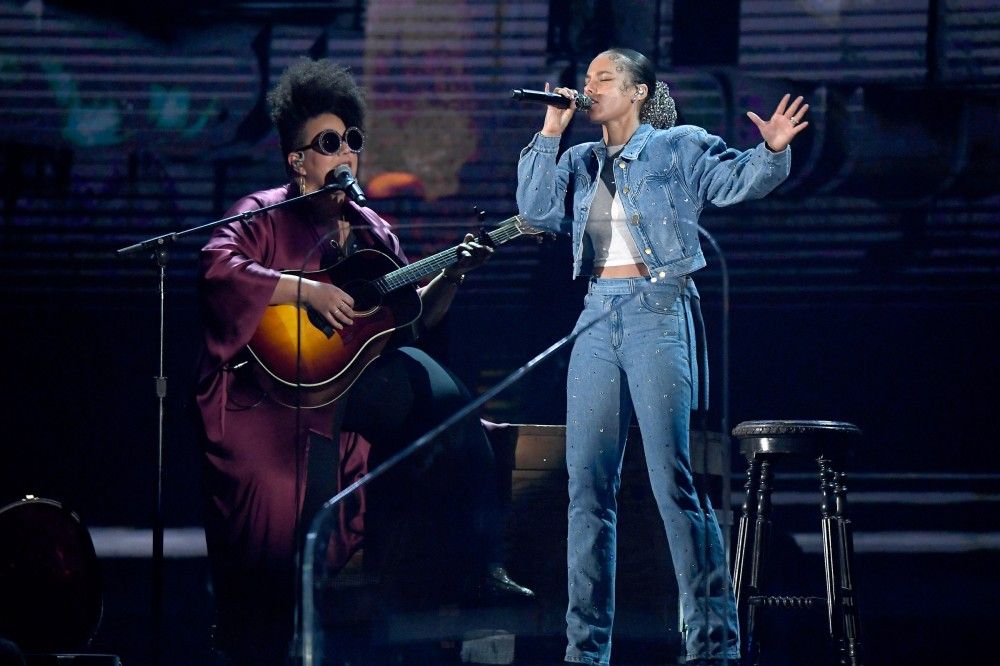

Ozzy Zig Finds Gig: Osbourne lets loose at an Earth concert at Hamburg’s Star-Club, 1969.

Photo by Ellen Poppinga – K & K/Redferns/Getty Images

The roots of Black Sabbath’s sound lie in their early influences. Osbourne and Butler both recall their worlds opening up the first time they heard the Beatles. “When the Beatles came along, my whole life changed,” Butler says. “I started growing my hair, wearing fashionable clothes, and finding a meaning to life outside of religion and school. It was great being in England in the 1960s because there was one great group after another.” Some of his favorites included the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, the Who, and the Animals, and, later, Led Zeppelin. He and Iommi shared a love for Jimi Hendrix, John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, and Cream. Butler credits the latter group’s singer-bassist Jack Bruce with inspiring his own adventurous bass style.

“I saw Cream three times when they played in Birmingham,” Butler says. “Jack Bruce definitely opened my eyes as to what a bass player could do live. I went to see Cream mainly because of Clapton, not knowing much about Bruce and drummer Ginger] Baker, and though the whole band blew me away, I was mesmerized at Jack Bruce’s playing. I didn’t know a bass player could do those things, filling in where the rhythm guitar would normally be. Later on, I went to see Ten Years After, and Leo Lyons greatly impressed me too, so I’d say a mixture of Bruce and Lyons were my main influences as far as playing style and approach.”

The group’s love for English blues rock led them back to these bands’ American source material. Butler caught many of the blues and soul artists that toured through the U.K., including Otis Redding, Wilson Pickett, Sam and Dave, John Lee Hooker, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Howlin’ Wolf, Sleepy John Estes, and Willie Dixon. Simpson remembers Osbourne poring over his jazz and blues records. “He certainly liked a guy called Jimmy Rushing, who sang with Count Basie’s Orchestra in the 1930s and 1940s,” the manager says. “In fact, the first thing that Ozzy ever recorded, or that Black Sabbath ever recorded, was called ‘Evenin’,’ which was a Jimmy Rushing song recorded with Basie.”

“I don’t even remember half the names of the bluesmen we liked] because you’d have a record and put it on, and, ‘Oh, yeah,’” Iommi says. “We got hold of just some blues albums, didn’t even know who they were. We’d play them and learn the songs and put them in the set lists.”

Early Earth concerts featured a mix of songs by Elmore James, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Robert Johnson. “We played stuff like Robert Johnson’s] ‘Dust My Broom,’ ‘Crossroads,’ ‘Big Bill’ Broonzy’s] ‘Moppers Blues,’ and the Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation’s] ‘Warning,’” Butler says. A bootleg of a late-1969 concert finds them also playing Buddy Guy’s “Let Me Love You” and Elmore James’ “Early One Morning”; also heard here is “Warning,” a slow-building brooding number about a man rueing the day he’d met his lover that eventually becomes a sprawling showcase of Iommi’s prowess. They even occasionally did “Blue Suede Shoes.”

But just as the band was finding its groove, things nearly fell apart. After opening up for Jethro Tull in November 1968, that group’s frontman, Ian Anderson, offered Iommi the chance to join his band as a replacement for Mick Abrahams. Tull had already found their identity — Anderson was the group’s flute-tooting ringleader — and the music was still rooted in the blues, so Iommi accepted. His Tull time lasted only a couple of weeks, just long enough for him to appear in The Rolling Stones’ Rock and Roll Circus and to see how an efficient band could be run. He decided Tull weren’t for him, and in December 1968, Iommi returned to Birmingham where he told his Earth bandmates that they needed to get serious if the band was going to have a future.

Jethro Tull’s regular rehearsals had impressed him, so he asked Earth to start convening at nine in the morning, jamming until lunch, and then jamming some more. “I said, ‘This is how they do it. Let’s have a go at it,’” the guitarist recalls. “Trying to get Geezer out of bed at that time in the morning was bloody hard, but we did, and we rehearsed, and we really worked at it then because it just felt that we had something to work for. I’d left a big band at that time, so to come back to our band, it was like, ‘Oh, blimey, he’s come back. We better pull our socks up.’ And I think everybody felt like that, including me.”

Earth’s first original song was “Wicked World,” a hard-rocking indictment of self-serving politicians who start wars and let the poor die at home. It starts with Ward’s skittish cymbals and Iommi’s lightning-fast guitar leads before crashing down in Sabbathian glory into a swinging blues riff. Osbourne bellows the first line, “The world today is such a wicked place,” and the riff gets fatter and fatter before breaking into a psychedelic swirl. The tune showed real style and intent. In just under five minutes, it laid out a blueprint for the doom and gloom the band would explore on future songs.

More than 50 years later, Ward still marvels at the directness of “Wicked World.” “It was now 1968, 1969, so we were very upset about a lot of different things,” he says. “I think all of us were one way or another always pissed off at something. I know I was.” That pissed-offedness led him to feel a disassociation from the flower-power counterculture of the time. “It was very difficult for all of us to get our heads around being loving towards each other and things like that,” he says. “That was not the environment that we’d been brought up in. Black Sabbath was detached from that.”

That detachment from hippie idealism would become even more stark on the next song the group wrote. “Black Sabbath” was born early one morning during a rehearsal at the Aston Community Centre. “I was really into classical composer Gustav Holst’s] The Planets around that time,” Butler recalls of the music’s inspiration, “and I was trying to play the first movement] ‘Mars, the Bringer of War’ on my bass, which I think influenced Tony to write the riff of ‘Black Sabbath.’”

That riff captured the essence of heavy metal. Its three notes were so discordant, so gloomy, so depressive that they spoke volumes on their own. Like the Holst piece, the riff revolves around a diminished fifth, a sinister sound that 18th-century music scholars referred to as diabolus in musica, or “devil in music.” Osbourne picked up on the vibe and bellowed, “What is this that stands before me?” drawing on the imagery of a nightmare Butler had told him he’d had, where he’d felt an unnerving presence in the room with him. The results sounded terrifying, and the band loved the feeling, so they played it over and over and over again to remember it, since they had no tape recorder.

“We were all so proud of ourselves when we wrote ‘Black Sabbath,’” Butler recalls. “I think it took a couple of hours to write it from top to bottom. Tony played the riff and we all just joined in. Ozzy spontaneously sang the lyrics. Then Tony topped it all by coming up with the menacing riff at the end. We knew it totally represented each one of us.”

But as with many later Sabbath classics, the group made the song feel weightier with a moment of reprieve, a hushed verse that built the tension until Osbourne let out a blood-curdling scream. “When we were writing songs, I always used to think, ‘It’s light and shade,’ hence the ‘Black Sabbath’ track, with the quiet part,” Iommi says. “You’d drop down and then turn up the volume for the loud riff to give it some kind of excitement.…’Wicked World’ was a bit jazzy, but when we’d done ‘Black Sabbath,’ that was then where we were coming from. That’s where we wanted to be.”

Courtesy of Rhino

The guitarist doesn’t specifically cite Holst’s “Mars” as an inspiration for the riff, but just unearthly orchestral music as a whole, the type he’d heard in the fright films that Britain’s leading studio, Hammer, made starring Christopher Lee as Dracula and Frankenstein. “In them days, Geezer and myself used to be really into horror films, and we still love music that’s got a little bit of power,” he says. “In some of these horror films, the music was a bit scary and creepy to go with the film. And I looked at our songs as being a similar sort of thing, like trying to make it sort of creepy.”

The song didn’t have a poppy chorus that might provide an obvious title, so Butler also looked to film for an inspiration. “I called it ‘Black Sabbath,’ after the Mario Bava film of that title,” he says, referring to the Boris Karloff horror anthology that came out in 1963. “I always liked the sound of it.”

He liked the sound of it so much that in September 1969 when Simpson insisted that they change their name to something other than Earth, because it seemed generic and there were other bands with the same name, Butler again suggested Black Sabbath.

An early version of “Black Sabbath” that Ozzy Osbourne culled from his “basement tapes” in the Nineties

“Funnily enough, Ten Years After guitarist-singer] Alvin Lee, who was sort of a mentor at that time, thought the name Black Sabbath was too heavy and he suggested Paper Sun, which none of us liked,” Butler remembers. “The song ‘Black Sabbath’ perfectly summed up the band both musically and personally at that time.”

“It’s the name that led them into that style,” Simpson says. “A name like that is a statement of intent.”

When they introduced “Black Sabbath” into their set lists, they were pleased with the way people took to it — or at least the way people were unsettled by it. “The audience was small, and nobody really knew quite how to react to it,” Ward says. “But we put so much into the song onstage that everybody just started to nod to it, especially towards the endings and the very loud parts. People were just like, ‘Wow, holy cow.’ I think we were blowing them away very quietly.”

“All the girls ran out of the venue screaming,” Osbourne recalled in his autobiography, I Am Ozzy. “‘Isn’t the whole point of being in a band to get a shag, not make the chicks run away?’ I complained to the others, afterwards.”

“The song ‘Black Sabbath’ epitomizes all that Sabbath means with masterful riffs, the words, and the overall impending darkness and doom that create ungodly emotions that to this day unsettle me,” says Judas Priest’s Halford, who was privileged enough to see Black Sabbath perform live in their infancy. “I have vague memories of seeing them as Earth in an obscure club in Birmingham, and they were in a sort of heavy-blues, jazzy-prog mode musically,” he recalls. “There wasn’t much of anything going on visually to remember. I can only recall the very first Sabbath songs like Crow’s] ‘Evil Woman,’ which was a cover. There was still some freeform noodling going on when they played live, but essentially the heaviness was dominating.

“When they became Black Sabbath, they had homed in on their identity more,” he continues. “Tony’s riffs played an immediately stronger role, and they now had a unique character that set them apart from everyone else locally or any other band around. Ozzy looked and sounded special, and the dynamic of Geezer and Bill set them up with a sound no one could match.”

Simpson also remembers the excitement of the band’s early concerts. “People would stand on the stairs just to hear the band,” he says. “People couldn’t even get in the room. But the band played loud enough. People could stay home, five miles away, and hear it out the windows.”

“Sweat rolling off the walls and the smell of cigarette smoke — and a little bit of other stuff — and the smell of stale beer,” Ward says.

After “Black Sabbath,” none of the band members remember exactly which original song they wrote next, since the tunes started coming so quickly that it became a blur. What they knew, though, was that they liked playing heavy.

Tuesdays Bluesdays: Osbourne (third from left) rehearses with members of Bakerloo Blues Line, Tea and Symphony, and Locomotive as they prepare for a showcase called the Big Bear Folly in 1968. Jim Simpson, seated, is wearing a white sweater and reviewing papers with a booking agent.

Photo by Bill Zygmant/Shutterstock

“Everybody wanted to be ‘heavy’ for a little while,” says Francis Rossi, frontman for Status Quo, a group that gigged with Sabbath early on. Playing heavy, in his opinion, was a rejection of pop. “The only one that did sound heavy was them. They were kind of thick sounding. The bottom end seemed very huge, and they sounded thunderous in a way. It was weighty.” (Years later, Osbourne recorded an especially heavy cover of Status Quo’s “Pictures of Matchstick Men” with Type O Negative.)

“When Zeppelin had that big drum sound, everybody wanted that,” Ten Years After bassist Leo Lyons says. “Then everybody wanted the loud, distorted guitars. That, to me, is what heavy was about. It was like a race at the time to be the heaviest.”

As the band developed its sound, Iommi learned that in order to write “heavy,” he had to be in a dark state of mind. “I’d sit in a room and start imagining what sort of thing I wanted to play, like an actor putting himself into a part,” Iommi says. “But in the early days, it was probably hash or something that brought out our vibe. I never used to smoke it at all, but when we did start smoking, bloody hell, all sorts of things would pop out, good and bad. But even then, I would have probably still put myself in a mindset, imagining something that’s big and demonic or whatever, and try and put it into music.”

Iommi also found himself writing girthier riffs in the years since he lost his fingertips. Prior to the accident, he could play all the big, extended jazz chords he loved on his favorite albums. Afterward, it was more difficult, so he played simpler, chunkier riffs. “Even to this day it’s still a problem,” he says. “I had to try and come up with a heavier sort of sound for the Sabbath thing, because there’s certain things I couldn’t play. So I play a lot in E and let the open E string ring out. Eventually I got a way of playing that suited me.”

The group wrote “N.I.B.,” a walloping bad-acid trip about a hookup with Lucifer, during one of its stints playing residencies at places like Germany’s Beat-Club, where the Beatles also earned their stripes. The group would have to play up to seven 45-minute sets a day, no matter how few people showed up. It was a challenge to fill the time, so they often turned back to jamming. Ward once even attempted a 45-minute drum solo, but the club owners told them to knock it off. The hulking riff of “N.I.B.” bears a similarity to Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love,” but the way the band cuts it short is jarring and gives some heft to all of the promises Osbourne, a.k.a. Beelzebub, is making to his betrothed.

“I wanted to put a humorous aspect to the lyrics in ‘N.I.B.,’” says Butler, who wrote the words. “I always heard the cliché of someone in love promising their loved one the moon and the stars, etc., so I thought if the devil fell in love, he could indeed promise the moon and the stars; he does have that power.”

“We got stoned in the dressing room, and in them days the Star-Club was pretty grubby,” Iommi says, describing the origins of the song’s odd title. “So we’re in this dirty, old dressing room, smoking some dope, and one day Ozzy said to Bill, ‘Bill, your face looks like a pen nib.’ And it just stuck. We always call Bill ‘Nibby.’ Then it got into the song, ‘N.I.B.’ The title was ‘Nib,’ but we put the dots in there to make it ‘N.I.B.’ Some people have said they thought it stands for ‘Nativity in Black,’ which sounds like the posher version, in’nit?”

“Sleeping Village,” the darkest song on the album, originally started out with the title “Devil’s Island,” and it finds Osbourne howling over Iommi’s quietly plucked guitar line and some ghostly mouth harp played on the recorded version by producer Rodger Bain. “We wrote the song to give the album a bit of light and shade,” Iommi says. Butler eventually changed the title to “Sleeping Village” because he thought it fit the tone of the song better.

“Behind the Wall of Sleep,” musically, combines the weight of “Black Sabbath” with the otherworldliness of “Sleeping Village.” The lyrics describe a surrealistic world where flowers can kill you and a “sleeping wall of remorse turns your body to a corpse,” over weighty blues riffs. “I was reading H.P. Lovecraft’s short story] ‘Beyond the Wall of Sleep,’ and actually fell asleep and dreamed all the lyrics and the main riff to the song,” Butler remembers. “When I woke up, I wrote down the lyrics, played the riff on my bass so I’d remember it — we didn’t have any recording devices back then, so everything had to be memorized — and played it to the others at rehearsal.”

A log sheet from Regent Sound Studio, the London studio where Black Sabbath would cut their debut album in November 1969, contains the lyrics to “The Wizard,” the Black Sabbath album’s bluesiest song. It shows that the original title was “Sign of the Sorcerer,” which someone scratched out — probably a good idea since the song is more to the point than that. It starts with Osbourne playing a harmonica and dives into a swinging riff. The lyrics describe a friendly Gandalf, strolling around, lifting spirits. “I was really into The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings at that time,” says Butler, who wrote the lyrics. “There wasn’t a lot to do in Aston at that time — two channels on TV that finished around 10 p.m., no money to go out much — so I used to read a lot of books, especially occult and horror stories.”

“What I love about the band is that we allowed our vulnerability to stick out,” Ward says. “When I think about the lyrics to ‘The Wizard,’ some people could probably feel that they’re laughable. But they actually meant something for us, and we were bold or brave enough to show ourselves from the inside out.”

That youthful verve also led the group to write much more than was necessary for an LP at the time. The Regent log sheet suggests they’d already come up with the song “Fairies Wear Boots,” which appeared on their second album, Paranoid, and Butler recalls that the group had written most of Paranoid’s “War Pigs,” other than the lyrics, at the time. Meanwhile, a lyric sheet for a song called “Changing Phases,” which recently went up for auction, contains the words to what would become the ballad “Solitude,” a song from the band’s third LP, Master of Reality; it’s credited “by Earth,” suggesting they had that song already, too. The group also cut a jazzy jam called “Song for Jim,” on which Iommi played a flute — a holdover interest from his time in Jethro Tull — that they never officially recorded but played live at gigs before recording the first album. (“I can’t even remember ‘Song for Jim,’” Iommi says now. “I remember the title, but I’m buggered if I can remember how that goes.”)

Despite the stockpile of originals, the group continued to play its blues covers live, as well as a few pop cover songs that sound out of place in the band’s oeuvre then and now. During a demo session in 1969, they recorded “The Rebel,” a jaunty, piano-driven rocker, written by Simpson’s Locomotive bandmate Norman Haines, that sounded a bit clunky when Osbourne sang it (especially when contrasted with the angelic, choral backup singers).

“We wanted to write our own songs and wanted to go in the direction that we thought was right for us,” Iommi says. “We didn’t want to play something that we didn’t want to play. What was the point of that, really? But Jim wanted us to do it, so we did ‘The Rebel,’ which was never a favorite for us.” The group never officially released the song.

The pop cover that did make it to market, though, was a brassy number originally written by American hard rockers Crow called “Evil Woman Don’t Play Your Games With Me,” a sort of get-away-from-me kiss-off song that had come out that year. “The song idea came from a guy who was going through a situation at the time like the one the lyrics describe, and the rest was some imagination and experience,” says David Waggoner, Crow’s singer. “I felt we did the song heavier live than how it was recorded, and the producer and label put the horns on it without our knowledge. I did not like the horns at the time, but now I go out with a 10-piece band, horns and all.”

Simpson had been working hard to get Earth a recording contract and had almost consistently struck out, until a music publishing company called Tony Hall Enterprises offered to take them on. That company suggested “Evil Woman,” thinking it could become a hit for the band. The group recorded a somewhat more stripped-down version of the song, compared to Crow’s, in November but wasn’t happy with it. “I wanted to move on from ‘Evil Woman’ because it had that word ‘evil,’ and we thought it had been really overused throughout rock’s history,” Ward says. “We recorded it, and I think I listened to it once and that was it. For me, it’s too over-pronounced.”

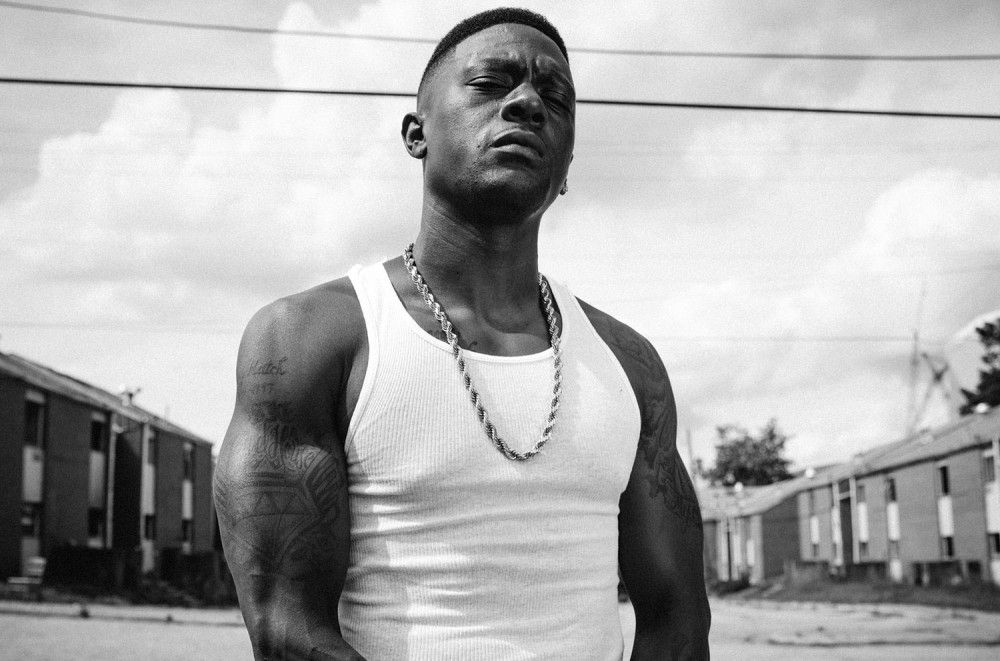

Iommi playing the Gibson SG that would define the sound of Black Sabbath at an Earth gig in 1969

Photo by Ellen Poppinga – K&K/Redferns/Getty Images

“I felt they recorded it too slow,” Waggoner says. “I personally like Tina Turner’s version of the song better.”

Despite Black Sabbath’s disinterest in the song, “Evil Woman” became their first single, backed with “Wicked World,” but it failed to chart. It also led off the second side of the original U.K. pressings of Black Sabbath.

By the end of 1969, Black Sabbath’s following had grown exponentially, and they were playing regular gigs around the U.K. People enjoyed their chilling horror-rock vignettes and blues repertoire, but even though they had a fan base, no record company wanted anything to do with them. Simpson pleaded his case to Tony Hall Enterprises, the publishing company that handled his other bands, and Hall agreed to give him a reported £600 for the group to cut a record. Simpson would put the LP out himself if he had to. So he booked the group for two 12-hour sessions at London’s Regent Sound Studio on November 17th and 18th, 1969, squeezing the dates in between the band’s gigs.

“Our manager at the time suggested that we stop off at this recording studio and do these songs we were working on,” Osbourne once said. “We got out of the van, played a bunch of stuff. And really, the first Black Sabbath album was really a live album with no audience and a few overdubs.”

Since Black Sabbath were an unknown quantity to the record industry, the publishing company requested that one of its producers, a young, unproven talent named Rodger Bain, handle the sessions. He’d overseen the band’s session for “The Rebel” that summer and “Evil Woman” earlier that month, so he already had a good rapport with the band.

“Rodger Bain was a very nice, charming, urbane man,” Simpson says. “He was very pleasant to work with, but he did nothing in the studio except to say, ‘OK, let’s try the next song,’ and press ‘record’. There were hardly any retakes on the first album.”

“I really liked Rodger a lot,” Ward says. “He was the right guy for us. This was a band that’s coming off the road, off gigs. So we were pretty riotous. And he was able to take that energy and make it sound right.”

The engineer on the project was Tom Allom, who was also new to his career. His most notable recording at that point was Genesis’ 1969 debut, From Genesis to Revelation, and he had previously manned a four-track demo session for Sabbath. “Black Sabbath were young, a bit younger than me, and they were outspoken and a bit wild,” Allom recalls. “But there was no time for playing around. It was like, ‘Gotta get the album done by 10 o’clock tomorrow night.’ So it was very businesslike. They were just rough diamonds from Birmingham but very, very well-prepared and very tight.”

The engineer, who has gone on to produce defining works for Judas Priest and Def Leppard, still marvels at Black Sabbath’s music. “I’d never heard anything like it,” he says. “Nobody had heard anything like that. I didn’t even know if I liked the music or not. It was very strange to me.” Allom recalls Iommi’s guitar sounding “unbelievably loud.” The band recorded its parts together, and Osbourne handled his vocals later. But overall, Allom uses the word “excruciating” to describe the volume of Sabbath’s performance.

“We had a film studio above us, where they used to shoot TV ads,” Allom says. “They did a lot of animation, which meant the camera dolly had to stay totally still while they moved the objects that they were animating. And I got a phone call going, ‘What’s going on down there, Tom?’ Geezer Butler’s bass was playing havoc with this great, heavy film dolly. It was just waltzing across the floor. I had to say to Geezer, ‘I’m very sorry, but this studio is only £10 an hour, but up there it’s £100, and they’re getting a bit cross.’

“I had to persuade him that we had to put his bass direct into the board, instead of using an amp,” he continues, “and he didn’t like the idea of that until he heard the playback and he said, ‘That’s the first time I ever heard my bass on a recording.’ Coming out of the amp, it just sounded like this great sort of big, flatulent, flabby sound.”

Ward found the whole experience alien. “I had an isolation booth, which I hated because I’m used to being outside, working with the guys,” he says. “And my drum sounds were all muffled and I hated that. I didn’t feel like I had any power in my drums. No disrespect to Tom] though. I’m still working with engineers on how to get my drum sound today.”

Iommi also had to make concessions to get the record done, when he ran into guitar troubles. “I played ‘Wicked World’ on my Strat and then the bloody pickup went out,” he says. “And in them days it weren’t like now, where you can go, ‘Oh, I’ll go and get another one from the guitar shop or get somebody to bring one over.’ Because we were only in for the day to record, to actually put the tracks down, I had to use the Gibson SG I’d brought with me as a backup. And I thought, ‘Oh, no, it’s just typical.’ But I had customized the Gibson a bit, so it felt more OK for me to play. So I ended up doing all the rest of the songs from the first album on the Gibson.”

That meant, that he had to pull off all of the six-string fireworks on “Warning” on an instrument he was relatively unfamiliar with. Luckily, he had had a lot of practice on the song.

“When we did ‘Warning,’ I think that was like 30 minutes long onstage,” Ward says. “But back in the day we used to do, like, three-hour sets, so it fit.”

Even half a century later, Iommi still sounds stressed out when he thinks about the performance anxiety that came with getting that solo right. “You only had one stab at it,” he says. “I said, ‘Look, just let me have another go at doing the solo.’ They said, ‘We haven’t got the time.’ ‘Just let me have a go.’ And I did have another go, and it weren’t as good, because I was so nervous about the whole thing, trying to get it done in the time. So we ended up, I think, using the first one.”

“Ozzy was almost hoarse by the time we finished recording, and I remember he wanted to redo the end of ‘Warning,’ but there wasn’t enough time,” Butler says.

“I think that all of us probably did the best we could,” Ward says. “The biggest thing for me was the fact that we’d made a record, and I couldn’t believe that. We’d actually made a record. Like, ‘Holy cow.’ “

“Of course, we knew nothing about mixing, so once we had used up our two days in the studio, we went on our way,” Butler says. “I am amazed that we did so much in so little time. We didn’t hear the final album until a week or so before it was released.”

Black Sabbath arrived in stores on February 13th, 1970. Sometime after the group recorded the album, it signed with Phillips’ freshly launched Vertigo imprint. Simpson remembers the signing occurring after label president Olav Wyper had passed on the group at CBS but had an about-face when he went to Vertigo. Wyper remembers it differently. He recalls seeing Black Sabbath live at a pub in Birmingham one night and being so impressed by their energy and the crowd they drew that he wanted to sign them; he couldn’t have turned them down at CBS since he wasn’t in A&R. “The bands on Vertigo had to be able to deliver live,” Wyper says. “We didn’t sign anybody that we hadn’t seen live, because the live connection with an audience is much easier than a recorded connection.”

The label head sorted out the business end with Simpson and his associates and decided to capitalize on the band’s creepy mystique by putting out the album on Friday the 13th. “In England, that’s a day when you don’t go out, you don’t take any risks, you stay at home,” he says. “Terrible things can happen. Friday the 13th? Good God, no. So putting it out that day was quite deliberate.”

Shortly before its release, Simpson met the band at Birmingham’s New Street Station, where he presented them with the album art. The sleeve was a gatefold, and its eerie cover depicted what looked like a witch standing in the woods, outside a cottage. The sky is pink, and the band’s logo is written in gothic lettering. The inside cover depicted an inverted cross that contained the album credits along with an evocative, disturbing poem about rain, darkness, blackened trees, swans floating upside down, and a young girl waiting as the “long black night begins.”

The design was credited to “Keef,” who was, in fact, Keith Macmillan, a young photographer whom the Wyper had recruited after another shutterbug had introduced them. He’d taken to using the name “Keef” since another, more established photographer had his name. Wyper was a go-getter and turned Macmillan loose to do what he wanted.

The artist picked up on the darkness of the music. And even though he didn’t pay too much attention to its lyrics, he liked what he heard. “To be honest, it was the first time I really enjoyed that kind of heavy rock,” he says. “But that album made me a fan for life.”

Osbourne having a smoke between songs in the recording studio, 1970

Photo by Chris Walter/WireImage

He decided that Mapledurham Watermill, a 15th-century structure in Oxfordshire that he’d scouted for potential shoots, looked run-down and bizarre enough to match the vibe of the music. He hired model Louisa Livingstone partially because she was five feet tall — so everything else would look big — and had her pose a variety of ways until he found one that looked right. “She wasn’t wearing any clothes under that cloak because we were doing things that were slightly more risqué, but we decided none of that worked,” he says. “Any kind of sexuality took away from the more foreboding mood. But she was a terrific model. She had amazing courage and understanding of what I was trying to do.”

“I remember it was freezing cold,” says Livingstone, who was 18 or 19 at the time of the shoot and later appeared in art for records by Fair Weather and Queen. “I had to get up at about 4 o’clock in the morning. Keith was rushing around with dry ice, throwing it into the water. It didn’t seem to be working very well, so he ended up using a smoke machine. It was just, ‘Stand there and do that.’ I’m sure he said it was for Black Sabbath, but I don’t know if that meant anything much to me at the time.” (When she heard Black Sabbath later, she decided it wasn’t her kind of music. She now records electronic music under the name Indreba.)

Macmillan shot the image using Kodak infrared aerochrome film, which he says was originally made for aerial shots, and gave the picture its pinkish hue. To add to the darkness, he brought a stuffed raven and put it on a tree stump for the back of the gatefold, and he gave Livingstone a live black cat to hold. Once he started designing the rest of the packaging, he figured the upside-down cross “just went with Black Sabbath,” and his assistant, Roger Brown, wrote the poem that went in it. “He was quite proud of that,” Macmillan says. “It’s such a creepy poem.” One of his collaborators, Sandy Field, did the typography for the logo, which made the cover look even more occult-like.

“I love the front cover,” Ward says. “I thought it was mysterious. It’s kind of like where we kind of hung our hats, to be honest with you.” But when he opened it up, the inverted cross bothered him. “That wasn’t who we were,” he says. “And nobody had talked to the band about that. I was guarded about the record company that we were with after that.”

“We’d created this image as a band, and they had rubbed it in more with the inverted cross,” Iommi says. “It helped in a lot of ways and also caused a lot of problems as well, because people would think we were bloody witches and God knows what else. People didn’t know what we looked like or anything, so it created this fear.

“I remember seeing something on TV once, where they were interviewing fans at one of our concerts,” he continues. “They said, ‘Why do you like this band?’ And the fans said it was because we were frightening. There was always this fear. They’d be frightened to talk to us or think we’re going to turn them into a frog or something. But it built up this image that got bigger and bigger. And of course, the inverted cross probably didn’t help to make it a better image in a nicer way.”

After the band members shook themselves free of Livingstone’s spell, they put the needle on the vinyl and heard some of their songs in new ways. Unbeknownst to the band, Bain and Allom had used some of the two days they had to mix the album to add the rain and thunder effects to the beginning of “Black Sabbath.” These sounds made everything even more uncanny.

“We rented a set of tubular bells, and we just clanged one of them,” Allom recalls. “I sort of made it fade in and out with reverb here and there, like when you’re standing in a field and a village church bell rings, as it comes and goes in the wind. It is iconic, isn’t it?” They also added some echo to Osbourne’s voice on “Behind the Wall of Sleep,” to make it sound even trippier, Bain played the jaw harp on “Sleeping Village,” and they doubled up some of the guitar solos.

“We really liked the rain and that sort of stuff,” Iommi says. “And I liked how there were two solos on ‘Sleeping Village’ over each other. It was a good effect. Rodger came up with some good ideas.”

“That storm at the beginning of the song “Black Sabbath,” I swear to you, I believe is the greatest introduction to any rock record ever,” Simpson says. “If you had asked the band if they wanted that, they probably would have said no. If you tried to describe it, it would have sounded horrible. But it was just perfect. That was all Rodger Bain.”

But what stands out most about Black Sabbath now is how unproduced it is in many ways, and how its starkness made everything sound more raw and unwieldy. “On the way back from recording, we had said, ‘Rodger Bain has done nothing,’ ” Simpson recalls. “He was this poncy London producer, fancy pants, coming here telling us what to do. He didn’t do anything, just pressed ‘record.’ And it took me a long time to realize that was pure genius. Producers often try to insert themselves into a recording. It takes great judgment to sit there and just say, ‘This is right. I don’t need to mess with it.’ Rodger got that.”

“The first Black Sabbath album stayed on the charts for quite some time,” Osbourne recalled. “I was like, ‘Why?’ It was such a great surprise.” Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

“I’ve often said that with Black Sabbath you ought to have put a lasso around the sound and pulled it in,” Ward says. “That’s the best way to record Black Sabbath.”

The unfiltered sound of Black Sabbath quickly took hold of English music fans. Although the “Evil Woman” single was a flop, Black Sabbath’s album slowly started ascending the charts. Thanks to airplay from John Peel, the band’s furious touring schedule, the record’s ominous cover, and good old-fashioned word-of-mouth, the LP became a hit.

“I can remember, as if it was yesterday, being in a club in Birmingham, and I’ve got a small fucking advance, so I went out on the town looking for the chicks,” Osbourne recalled once in Rolling Stone. “And Jim Simpson comes up to me and says, ‘I’ve got some news to tell you.’ And I go, ‘What’s that?’ And he goes, ‘Your album enters the British charts at 17 next week.’ And I go, ‘Fuck off, you’re winding me up. No way.’ ‘No, it’s true.’ And that was it. And the first Black Sabbath album stayed on the charts for quite some time. I was like, ‘Why?’ It was such a great surprise.”

Beginning on March 7th, 1970, Black Sabbath spent 42 weeks on the British charts, topping out at Number Eight. The album came out in the U.S. in June, eventually peaking at Number 23 around Christmas. Black Sabbath has since been certified gold in the U.K. and platinum in the U.S.

It was the sound of Black Sabbath that sold the album. Macmillan hadn’t included a photo of the group on the sleeve (he can’t remember why), so all listeners could look to for a sense of the band was its monolithic songs. Simpson recalls playing up the band’s gloominess in advertising materials, saying, “Black Sabbath makes Led Zeppelin sound like a kindergarten house band.”

Although the LP was a hit with fans, rock critics savaged the group’s sound. In the U.K., they faced slings and arrows for the cover art’s satanic imagery. Disc & Music Echo described the album as a whole as a marketing ploy, “Black Magic Music for the Sick Masses,” and suggested a warning be placed on it that said, “We strongly advise those of nervous disposition NOT, repeat NOT, to listen alone.” Meanwhile, Melody Maker described the record as “heavy going,” and a review in International Times that year likened them to “a runaway bus: fast & red & frightening.” In the U.S., Rolling Stone dismissed the album as sounding “just like Cream — but worse!”

“Being trashed by Rolling Stone was kind of cool, because they were the Establishment,” Osbourne wrote in I Am Ozzy. “Those music magazines were all staffed by college kids who thought they were clever — which, to be fair, they probably were. Meanwhile, we’d been kicked out of school at 15 and had worked in factories and slaughtered animals for a living, but then we’d made something of ourselves, even though the whole system was against us.”

“The press had to eat their words in the end,” Allom says. “They went on to become one of the most famous bands that ever lived.”

What solidified their fame, though, was the way they built on their sound, making it even more powerful. After a middling prog-rock band changed its name to Black Widow and aligned itself with a famous sorcerer in England, Sabbath distanced themselves from writing about the devil and refocused their lyrics more to address social issues. They rewrote the song “Walpurgis” — originally about witches — and retitled it “War Pigs,” revisiting the theme of evil politicians, and crafted two other songs about war, “Electric Funeral” and “Hand of Doom.” By the fall of 1970, they headed back to Regent Sound to work on their second album, War Pigs.

Right when they thought they were done, Bain asked for one more song to fill out the LP, and Iommi came up with the riff for what would be “Paranoid.” The song, a charging, three-minute barnburner, became an instant hit, making it up to Number Four on the British chart and securing them a spot on the TV show Top of the Pops. The record company retitled the album Paranoid — making the record sleeve, which depicted a “war pig,” look particularly odd — and the album became a smash, claiming the top spot on the British chart three weeks after its September release. It was certified gold in the U.K. and, after it came out in the U.S. in early 1971, it eventually went quadruple platinum. Although Rolling Stone gave Paranoid a laughably bizarre review upon its release (name-checking Black Widow’s singer), the magazine recently dubbed it the “Greatest Heavy Metal Album of All Time.”

On Black Sabbath and Paranoid, the band had created a unique sound, which it refined throughout the Seventies. Master of Reality featured more-compact songwriting, the cocaine-fueled Vol. 4 found them playing looser grooves, the demon squeals of Sabbath Bloody Sabbath returned them to the horror rock of their debut, and Sabotage showed off their technical skill on proggy, angry-at-the-world epics. The Sabbath saga spiraled on and on until the group ejected Osbourne and recruited Rainbow frontman Ronnie James Dio, who introduced more elements of fantasy to the band’s lyrics in the 1980s, while Osbourne became a solo superstar with a flashier style of metal. But their importance to an entire genre was unknown to them until later.

In the mid-Seventies, Circus magazine asked Osbourne what label he would use to describe Sabbath’s music. He said, “Depression rock.” In recent years, he’s said he hates the term “heavy metal” because it stretches from Sabbath to Poison.

Although the precepts of heavy metal — loud guitars! thudding bass! crashing drums! yowling vocals! brooding lyrics! — existed in the late Sixties on albums and singles by Blue Cheer, Iron Butterfly, and Grand Funk Railroad, the bands that ratified the genre in the late-Seventies and Eighties seemed to follow the model of Black Sabbath, as well as Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple, more than their American counterparts. Judas Priest, from just northwest of Birmingham, issued their first album in 1974 and became heavy-metal innovators two years later on Sad Wings of Destiny, with a sound that balanced the directness of Sabbath with the virtuosity of Deep Purple. Motörhead, Iron Maiden, and Metallica followed suit in the coming years, and by the early Eighties, the term “heavy metal” was like a religion for these bands’ fans, and Black Sabbath were their demiurge.

Sabbath’s members can’t remember exactly when they first heard their music described as “heavy metal” in a good way. “I think it was we were about two years in, and we were starting to be called ‘heavy metal,’ ” Ward says. “And I remember us all denying that furiously. Because it was a new word. I’ve only started to adopt that term for us in the last 10 years or so — so when I was 60, I started to accept the idea that that’s part of metal.”

“It can rightly be claimed that that moment that first album was released was the birth of heavy metal,” Simpson says. “Nobody else was doing anything like them. We’re compared to bands that we were nothing like them.”

Osbourne first noticed Sabbath’s impact on his 1986 solo tour, when Metallica opened up for him. “Every time I went past their dressing room on that tour, I clearly remember they were playing old Black Sabbath stuff,” he said in the liner notes to the recent box-set reissue of Metallica’s Master of Puppets. “And I genuinely thought they were taking the piss and winding me up. I said to my assistant at the time, ‘It ain’t cool, they’re trying to undercut me and make fun of me.’ He said, ‘What the fuck are you talking about?… They think Sabbath and you are gods!‘ It was genuinely one of the very first times that I realized people actually liked Black Sabbath.”

“We wanted to play what we liked,” Tony Iommi says. Black Sabbath perform at Alexandra Palace in London on November 16th, 2005. Photo by Dave Hogan/Getty Images

“I didn’t hear us cited as an influence until bands like Nirvana, Soundgarden, and Metallica, and some of the punk stuff, like the Stranglers, came along,” Iommi says. “Once people did start citing us as their influence, then the younger kids started listening. If Metallica would say, ‘Oh, well, Sabbath influenced us,’ then people would listen. That sort of helped it grow.”

As Black Sabbath’s legend blossomed, the songs on their debut became canon. Artists including Anthrax, Type O Negative, Beck, Pantera, the Flaming Lips, Danzig, and Foo Fighters, among many others, have covered the record’s songs. Meanwhile, the band Sleep made Sabbath worship a way of life, and the guitarist from Ozzy Osbourne’s solo band, Zakk Wylde, formed his own Sabbath tribute band, Zakk Sabbath, to keep the band’s music alive when he’s not on the road with the Prince of Darkness.

Throughout the Eighties and Nineties, Sabbath’s lineup changed regularly, with Iommi being the only consistent member. Meanwhile, Osbourne’s solo career skyrocketed, paving the way to reality-TV superstardom on The Osbournes. The original lineup of Black Sabbath reunited in 1985 for Live Aid, and again in 1997. Without Ward, they recorded a new album, 13, in 2013, which went to Number One around the world, and three years later embarked on a final tour, dubbed “The End.” They called it quits after a concert on February 4th, 2017, and announced their disbandment a month later.

Ward now plays in his own hard-rocking Bill Ward Band and another group called Day of Errors; he has lots of music he hopes to release, and says he has mended fences with the rest of the band. Iommi has been spending his time sifting through CDs he’s made of his riffs over the years, contemplating what he’d like to record next; he recently gave five or six CDs to his friend Brian May, and hopes that at some point he and the Queen guitarist could work on something together. Butler recently joined the hard-rock group Deadland Ritual, alongside musicians who have played with Billy Idol and Guns N’ Roses, and they have issued a couple of singles. And Osbourne has recorded a star-studded new solo LP, Ordinary Man, which will come out later this month. The artists all still look back fondly on their first record, because they know how special it was.

“What made us different was that we played loud,” Ward says. “There were a lot of other bands that played loud and aggressively, but they sang about relationships or other things, which is fine. But I’m very happy that Black Sabbath mostly didn’t. I liked the fact that we wrote about rocket ships and anything that was current. I used to think we were a bit odd, but it wasn’t until the 2000s, when we were doing Ozzfests, that we were playing with other bands that sang about social issues and not love.”

“We didn’t want to do the usual falling-in-love/breaking-up lyrics,” Butler says. “We wanted to write about the reality of working-class life and escapism.”

“All the time people used to tell us, ‘Oh, you’ve got to play more poppy stuff,’ ” Iommi says. “But we wanted to play what we liked. Because we listened to ourselves and believed in what we did, it happened for us. The first record is an iconic album. I just love the vibe on it. It was all so innocent for us.”