He Had a Billion-Stream Hit. Now His Songs Are in Limbo Until They Go Viral on TikTok

When singer Trevor Daniel topped one billion streams on Spotify for his breakout track “Falling,” the 27-year-old joined the ranks of Billie Eilish, Drake, Justin Bieber, Cardi B, and Ed Sheeran and other major global artists to hit the milestone.

Daniel can credit the emo-rap track’s success largely to TikTok. Despite its 2018 release, the song took off two years later as millions began to download the video-sharing app while cooped up at home during the onset of the pandemic. Daniel’s viral jumpstart led to collaborations with Selena Gomez and Lil Mosey for remixes of “Past Life” and work with Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter Julia Michaels on “Fingers Crossed.”

Daniel hasn’t released any new music since last November’s EP That Was Then, despite having songs in the pipeline — evident in the snippets Daniel has been posting. However, he tells Rolling Stone that until one of the teases takes off on TikTok, his tracks seem destined to stay in limbo.

“It’s just been pretty much impossible to put out music,” he says. “It feels like I’m at the DMV. Every time I go to deliver music, it’s like, ‘Oh, well you need to do this … post on TikTok more … tease these songs so we can see which ones they react to more. I do that and then I don’t really hear anything. Because what they’re really expecting, even though they say they’re not … they want it to go viral again.”

“It’s just really disheartening to be honest with you,” Daniel adds. (A rep for Daniel’s label, Alamo Records, did not immediately reply to a request for comment.)

“It feels like I’m at the DMV. Every time I go to deliver music, it’s like, ‘Oh, well you need to do this … post on TikTok more” – Trevor Daniel

The conversation around TikTok’s outsized influence in reshaping the music industry has been brewing since it became part of society’s lexicon during the pandemic’s early stages. It was appealing for smaller artists who could go viral with just one song, success that translated over onto streaming platforms.

For record labels, TikTok became the perfect tool not only to promote new music, but as a widespread focus group to test upcoming tracks. They only needed the song’s catchiest 15 seconds to gauge how audiences might react. In April, Jack Harlow built up a frenzy over his single “First Class” after the chorus went viral on TikTok days before it was dropped. Last summer’s anthem “Twerkulator” by City Girls sat on the shelf for months after the duo said they couldn’t get clearance for sampling Afrika Bambaataa’s 1982 classic “Planet Rock,” but when TikTok got a hold of a leaked version and the song began to trend, City Girls’ team was able to finally get clearance.

Snippets that resonated with listeners and trended on TikTok became a clear indicator to labels that the full track would do well upon release. But artists whose songs failed to make noise in the “teasing stage” were told, like Daniel, to keep promoting the single until it magically took off.

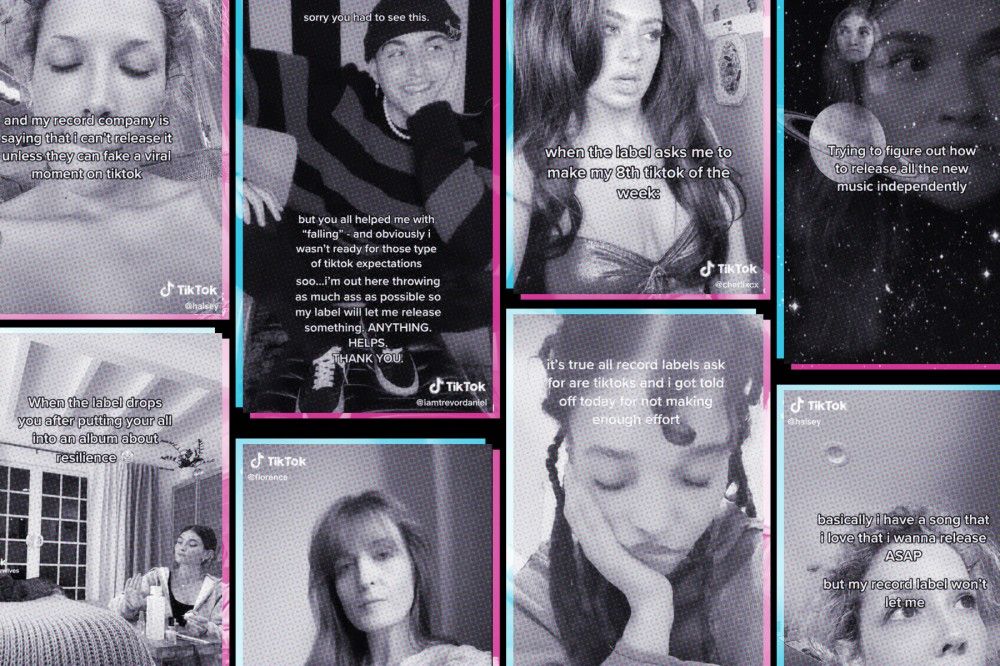

It’s exactly the situation Halsey (who uses she/they pronouns) described last weekend. Halsey — who aptly pointed out their eight years in the industry, 165 million records sold and three Grammy nominations — claimed their record label refused to release a new song until they were able to “fake a viral moment” on the app.

@halsey I’m tired

♬ original sound – Halsey

“Everything is marketing,” Halsey wrote in a TikTok that ironically went viral, as a portion of the new track played. “I just want to release music, man. And I deserve better tbh.”

In subsequent tweets and comments, Halsey clarified it wasn’t the directive to make TikToks that upset her but the vague instructions to post six videos that needed to hit an “imaginary goalpost of views” before the label would decide on a release date. “They just said I have to post tiktoks; they didn’t specifically say ‘about what’ so here I am,” Halsey wrote.

And even when Halsey began to trend on Twitter and the TikTok racked up nearly nine million views, it apparently still wasn’t enough to earn a solidified launch date. “Talked to my label tonight after my tiktok tantrum,” the singer later wrote on Twitter. “They said ‘wow the tiktok is going really strong!’ I was like ok cool so can I release my song now? They said, ‘we’ll see!’ tell me again how I’m making this up.” (A rep for Halsey did not respond to a request for comment. A rep for TikTok declined to comment. On Tuesday, Capitol Music tagged Halsey in a tweet and said it was releasing “So Good” on Friday, June 9, noting it “encourages open dialogue” and has “nothing but a desire to help each of our artists succeed, and hope that we can continue to have these critical conversations.”)

“All independent artists hear is ‘Put your songs on TikTok … and one day you’ll be big like Halsey. But if Halsey has to do it too, then what’s really the goal?” – Bronze Avery

Halsey’s transparency about their frustrations was a relief to smaller, independent artists who feel crushed by the newfound focus labels are putting on TikTok.

“It’s definitely a privileged problem to have,” says singer-songwriter Kailee Morgue. “But if it’s happening at that level, where those artists technically need to earn their releases, that it’s trickling down to people that are at the bottom of the totem pole.”

Singer Bronze Avery, who won Billboard’s first-ever NXT competition last year, says it’s been a dominating conversation among musicians recently. “All independent artists hear is ‘Put your songs on TikTok, do the snippets, do this over and over, and one day you’ll be big like Halsey,’” he says. “But if Halsey has to do it too, then what’s really the goal and is that cycle ever going to break?”

“It’s kind of wild,” Daniel adds. “I feel like it’s been going on for a while, but when Halsey posted what they did, it really helped me feel like I could speak out because it’s helpful to know it’s not just me.”

Soon after Halsey’s videos began trending, fans dug up videos of other artists complaining or acknowledging the practice. In a since-deleted post from FKA Twigs, the musician claimed that “it was true” that “all record labels ask for are TikToks” and she had been “told off” for not “making enough effort” when it came to making videos. (A rep for FKA Twigs did not reply to a request for comment.) Ed Sheeran posted a clip of himself eating a bag of potato chips, saying he decided it counted as obligated promotion for his song “2step” with Lil Baby. In March, Florence Welch let out a sigh before launching into an acapella version of “My Love,” explaining in her caption that her label wanted her to post more “low fi” videos.

@florence The label are begging me for ‘low fi tik toks’ so here you go. pls send help ☠️ x

♬ original sound – Florence

Even artists who thrive on the platform have made lighthearted references to being forced to post content. Doja Cat teased a collaboration with Taco Bell with a tongue-in-check gripe about the partnership. “I gotta do this fucking TikTok … they want me to rap about Mexican Pizza,” she said. “So, I just wanted to give you a heads up before you see that shit, it’s contractual. Shh. I know it’s bad.” (Artists are now even lampooning the phenomenon, with Charli XCX joking that she was “lying for fun” after claiming her label asked her to make eight TikToks a week.)

Regardless if the complaints are legitimate exasperation or clever reverse psychology marketing tactic, it’s clear that musicians are being asked to do more heavy lifting than ever when it comes to their own promotion. But the underlying issue isn’t the ask of creating content for TikTok, but the potential repercussions that can come when artists’ promotional content fails to hit an impossibly high target.

Indie-pop band MisterWives claim their label Fueled by Ramen dropped the group last summer for this reason. “It was wild for us because we’re a band that’s been around for about 10 years,” lead singer Mandy Lee tells Rolling Stone.

The New York-based quintet were in the midst of releasing their third album “Superbloom” when the pandemic hit in 2020. With touring off the table, Lee says the band, which is also composed of Etienne Bowler, Marc Campbell, William Hehir, and Mike Murphy, began promoting the emotive and personal 19-track album in all the ways they knew of, “pouring our heart and soul into being creative.”

“We produced music videos from home, we created a whole live stream that was like a theater performance of the entire album,” she explains. “We did countless interviews, like opening up about what the album was about, just very DIY, and did everything we possibly could.”

But it still wasn’t enough, according to the band. “I was told, ‘You weren’t willing to sell the story,’ because we weren’t pushing the album through the app,’” Lee says. “It was crazy that all that hard work was diminished and didn’t measure up to anything because we weren’t funneling it through TikTok.” (A rep for Fueled by Ramen did not immediately reply to a request for comment.)

@dojacat somebody gettin cussed out

♬ original sound – Doja Cat

It’s no surprise that labels are shifting their focus to TikTok, considering a song can go viral even before it’s even released, effectively guaranteeing a return on a label’s investment, Jesse Callahan, founder of social media marketing firm Montford Agency, explains to Rolling Stone.

But what labels tend to overlook, Callahan says, is just how unrealistic it is to expect an artist to be able to go viral with every single song — even more so if that determines what gets released.

“It’s not easy to put out viral content, to understand trends, to interact with your followers; that’s a lot of talent to do that,” he says. “There’s so much work and expectation that the label puts on you — away from just producing and writing music … to just say that this artist needs to be perfectly well-rounded to create viral social media content, that’s a big ask on top of all the other stress that they have with touring, producing music, and trying to have some personal life.”

It also offers another method for a label to save a few bucks. Teases of songs that fail to prove they will do well if released linger around until they gain traction, or risk never coming out at all — saving labels the cost of traditional promotion efforts when it comes to releases.

But it also ends up stiffing songwriters and producers in the process, who lose out on money when a song is leaked and doesn’t go anywhere, explains Lucas Keller, CEO of Milk & Honey, which manages the industry’s top producers and songwriters.

“What I’ve been calling it is, ‘Try before you buy,’ and I’m not for it,” he says. “If we let this happen, we have millions of dollars across all of our clients in production fees that are gonna go away. Because what record companies are going to say is, ‘We’re only going to pay you if a song reacts when you post it on TikTok.’ And then what happens is, a very small portion of records actually react and become global hits.”

“At a certain point in time, it became about the data and the numbers and not about the music” – MisterWives’ Etienne Bowler

Singer-songwriter Sizzy Rocket, who has written songs performed by Noah Cyrus, Hey Violet, and Timeflies, spent nearly 10 years with Universal Music Group under a publishing contract until she left this March, forming her own record label.

“Every major label has called me to be like, ‘Oh, come write for my viral artists for free — because the industry standard is that songwriters don’t get paid for the session,” she says. Her songs could go on to be recorded — but if more labels require a song to trend even before it’s released, how long does that mean she’ll have to go without being paid?

“Artists are fed up and I love it — I think we should be fed up,” she says. “To be exploited by these labels and have someone who has no idea what it’s even like to make a TikTok? … They don’t know what it’s like to really sit there and have to make these videos.”

Unlike Twitter and Instagram, TikTok content can take much longer to create, and requires users to be hyper-engaged with the app to jump on trends. Even if artists can quickly make videos, they still must appease the ever-changing algorithm, making sure they use the right hashtags and popular sounds. They also have to post content that’s not solely about their music — several artists tell Rolling Stone that their most popular posts have nothing to do with their latest song.

“When I was first getting used to the platform — and also for most people who are not tech-savvy — it can take hours and hours just to make one video,” Avery explains. “To get just a couple of hundred or even a couple of thousand views, it’s so disheartening to the process of being an artist. It feels so defeating when they say, ‘Okay, that was great, but now you need to do that three times a day, every single day.’”

British artist Emma McGann says while she understands the added benefit of promotion on TikTok for independent artists like herself, it’s still “exhausting” to create additional content — especially around new music releases. “I think it does lead to burnout for a lot of people, myself included,” she says. “It’s definitely a balancing act. I’d probably say I’ve spent four to five hours a day working on content, and not just across TikTok but all platforms.”

Even independent singer Jessica Foxx, who has built up a sizable following of 130,000 and consistently makes well-performing TikToks, says content creation isn’t something she would naturally gravitate towards. “I wouldn’t really consider myself a social media person,” she says. “I think I do have the personality for it … but I wouldn’t be doing it if I didn’t feel like I had to.”

It becomes an impossibly tall order when labels throw in the added pressure of wanting a song to have hype around it to determine if it should be dropped in the first place — effectively meaning artists have to earn song releases. And if songs fail to make buzz on TikTok, artists begin to question if a song they originally believed in is any good at all.

“It’s beneficial and harmful at the same time,” Morgue explains. “It’s weird. It can do so much good, because I’ve had a song that had a moment on there. The song doubled in streams and it’s like ‘Awesome, that’s great,’ but in the back of your head you’re like, how do I continue this? How do I make this happen with my other songs? You never really know why any of it’s happening.”

Daniel says he has found himself second-guessing his music if it fails to trend on TikTok. “It’s just like, ‘Fuck, what am I doing wrong? What made “Falling” click with people?’ I’ve asked that question because I don’t know. I make music every day and I feel like I put emotion into everything; I feel like I have cool melodies across the board. The things that people tell me about [“Falling”], there’s also parts of it in other songs. So, whenever those don’t do well, I’m just sitting here like, ‘Okay, what did I do wrong? Did I not put the text on the screen the right way? Did I catch them in the first three seconds? Instead of ‘how can I make these kids feel accepted?’”

Some artists say it can be easy to toy with the idea of caving in, creating a song they think might be better suited to TikTok, just to get themselves out of a rut or to appease a label. This creates a potential problem of genres slowly melting away until everything sounds like it could be a TikTok song.

“My issue is that, at a certain point in time, it became about the data and the numbers and not about the music,” MisterWives’ Etienne Bowler says. “It just kept growing and growing and TikTok is now the worst that it’s ever been because it’s all about data, numbers, pre-saves, all that. No one really seems to care about how good the music is.”

The artists Rolling Stone spoke with all agree that TikTok is a powerful tool — especially for smaller and independent musicians — but it’s unsustainable and unfair to solely rely on a social media app to determine what songs get released, or who gets signed simply based on if they have enough followers to make songs go viral.

“It is disheartening, and it is a disheartening growing pain,” Avery says. “Because ultimately, the tools are better. I can’t lie. I look at it very logistically in play — the tools are better. I’ve discovered way more music from TikTok, and I have on Instagram because of the way the platform is laid out. So, for me as a fan of music, I enjoy it way more and I feel like I connect to these artists in a different way.”

“I want to make my art and I want to connect with people,” Sizzy Rocket adds. “I can’t deny the fact that TikTok can be a useful tool to reach people. But when it starts becoming about, ‘You have to make these videos and you have to copy these trends and go viral’ and we start putting artists in these boxes — I think that is when it becomes problematic.”