Excerpt: Shakira, Daddy Yankee Break Down Breakthrough Hits in New Book

In Leila Cobo’s new book Decoding “Despacito”: An Oral History of Latin Music, the author and Billboard’s VP of Latin Music breaks down the genre’s biggest singles of the past 50 years in the words of the artists, producers and executives behind each song.

In this excerpt from the book, Shakira, her collaborators and then-Sony Music chairman Tommy Mottola talk about the decision to translate some of the young Colombian star’s hit Spanish-language songs into English, including “Suerte,” which became Shakira’s opening salvo in the U.S. mainstream, “Whenever, Wherever.” Daddy Yankee also goes deep on his 2004 hit “Gasolina,” the single that took reggaeton from the barrios of Puerto Rico to the top of the charts.

Other singles featured in Decoding “Despacito,” available now on Amazon, include tracks by Santana, Ricky Martin, J Balvin, Selena, Gloria Estefan, Luis Fonsi, Rosalia and more.

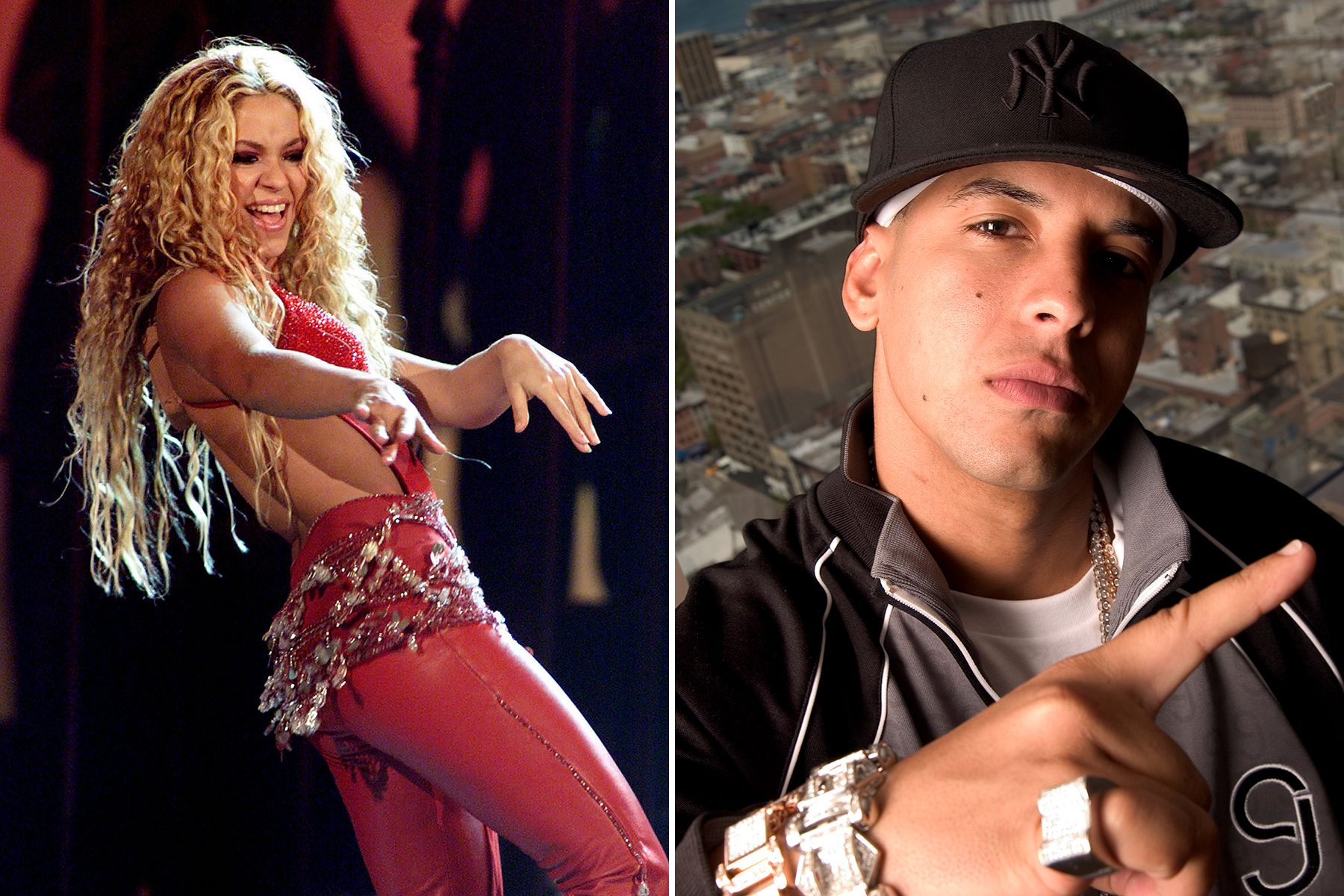

Shakira’s “Whenever, Wherever” (2001)

Ricky Martin’s phenomenal success opened the door for a string of Latin artists who waved the flags of their heritage, but who sang in English. The hits started coming out so quickly that the media and the industry coined the term crossover, created to identify those acts who began their careers in Spanish but could “cross over” into the English and global markets.

As Martin continued to top the Billboard charts, Sony Music Chairman Tommy Mottola was readying releases by Marc Anthony and Jennifer Lopez, both born and raised in the Bronx to Puerto Rican parents. But then he decided to take on an even bigger challenge. Why not release an English-language album by a Latin American artist? Mottola zeroed in on Shakira, the young Colombian star who was redefining the parameters of women in rock. Shakira already had multiple global hits under her belt, a multiplatinum-selling album ( ¿Dónde están los ladrones? [Where are the thieves?]), and a famous manager, Emilio Estefan, widely regarded as the most influential Latin music executive at the time. But not only was Shakira not from the United States, she didn’t speak English. Breaking her into the mainstream market seemed like a monumental task.

“Without question it was a challenge,” says Mottola. “I thought a breakthrough like this would be huge. Absolutely huge.”

An album was set in motion. Estefan and his wife, Gloria, who was close to Shakira and served as one of her mentors, encouraged her to write and sing in English. Gloria also stepped in to translate “Suerte” (which directly translates to “Luck”) into “Whenever, Wherever,” one of only a couple of songs on the album originally written in Spanish.

Once Laundry Service was completed, Mottola, as company chairman, made a decision. Shakira’s first English-language single would be “Whenever, Wherever.”

The song, aided by a Spanish version that was marketed to Latin audiences and a video that highlighted Shakira the dancer and showed her diving off a cliff, became her first charting title on the Hot 100 chart, peaking at #6 on the December 29th, 2001, chart.

It would become her second-longest charting title on the chart, staying for a total of 24 weeks (“Hips Don’t Lie” and “La tortura [The torture]” both charted for thirty-one weeks), and it would effectively break Shakira into the main- stream market, making her an international star.

Nearly 20 years later, the appeal of “Whenever, Wherever” hasn’t subsided. The song was part of Shakira’s Super Bowl performance on February 2nd, 2020. The following week, the song debuted at #54 on Billboard ’s Digital Song Sales ranking, while Laundry Service reentered the Billboard 200.

Tommy Mottola (Then chairman of Sony Music; now chairman of Mottola Media Group)

Shakira had been signed to our Colombian company since she was 14 years old. I had followed her career way back with her Spanish albums, and we had released ¿Dónde están los ladrones? and had huge success. I remember first meeting with her like a year and a half before [the album release in 2001], tell- ing her it would be a big step if she was able to do an album in English. She said, “I don’t know if I can do it, but I think I can.”

Shakira (Artist, songwriter)

I do think there was great anxiety surrounding the crossover. A part of me was definitely more anxious than I thought I was. But it was also something I’d waited for a long time. A dream was coming true. A longtime dream. The court was opening up, my field of play was expanding, and that didn’t come alone. It came with great challenges, like learning how to speak English properly, and giving a decent English interview.

Tim Mitchell (Artist, songwriter, producer)

I started working with Shakira in 1998 as sort of her musical director and playing guitar during the promotion of her ¿Dónde están los ladrones? album. After that, we did the MTV Unplugged album together, and then we jumped into Laundry Service, which was this whole next level of things. At the time, Emilio Estefan was also managing me as a producer, and I’d been playing guitar with Gloria since 1991 with the Miami Sound Machine. But when I met Shakira, I didn’t know who she was because I was kind of a gringo who grew up in Detroit. But we just kind of hit it off from the very beginning. All the music she liked was all the stuff that I was into: a lot of rock ’n’ roll, a lot of progressive, alternative music, and all this stuff. So we started writing together after rehearsals and just hanging out, and when it came time to write her English album, it was just more writing. We spent many weeks and months just writing. I went to the Bahamas a bunch of times and we went to Uruguay and wrote down there in Punta del Este, and there were a lot of people involved in the writing process of the album.

Shakira

I really wanted to do a song that brought together Andean sounds. I’ve always loved Andean music, the sound of the bombo leguero [a traditional Argentine drum], Andean flutes. I’ve always connected with that music, and I wanted to do some pop, something popular, but that also had that tint. I was clear in that I wanted to play with those ideas.

Tim Mitchell

I was always thinking of trying to write her a song like Natalie Imbruglia’s “Torn,” but that song was a very major harmony song. I was in Crescent Moon [Estefan’s studio in Miami] the day before I went back to the Bahamas to work with her, and I was thinking, “I need to find a way to do this [in a minor key].” I wanted to do like a four-on-the-floor kind of thing, and I came up with a kind of a minor chord version of what I thought was similar to what I was going after. In the Bahamas we had a nice little writing room at this house. It was awesome, and I just programmed a beat, drums, and these chords, and then once Shakira gets involved, everything is super creative. She had this idea for an Andean flute kind of thing and she pretty much sang it to me. At the time we were really into guitars, and she was into guitars and rock, so I tried to do like a Hendrix-y sort of rhythm part, and then that kind of became the guitar part. And then the intro part, there’s this guitar line [sings intro bars of “Whenever”]—I came up with that. I was thinking of it like a James Bond kind of thing.

I didn’t have any melody coming in. I just had the chords and the groove, and the idea. Then we got in the studio together, started riffing back and forth. She’s amazing with melodies. All the melodies, like [sings melody of “Whenever”], that’s all her for sure. I can’t stop her. She’s brilliant with melodies and stuff.

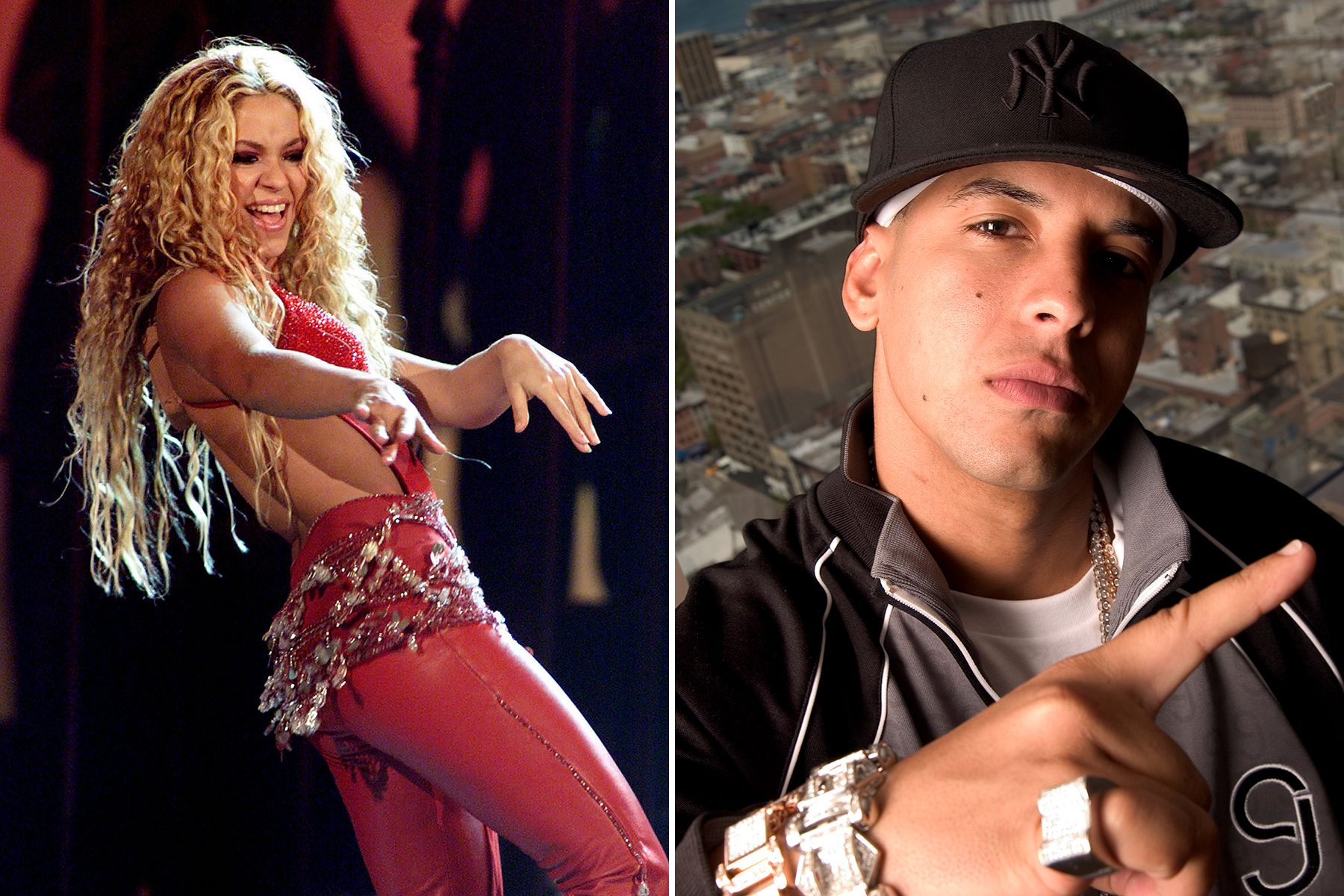

Daddy Yankee’s “Gasolina” (2004)

In mid-July 2004, an album titled Barrio fino (Elegant neighbor hood ) seemingly jumped out of nowhere into the #1 spot on the Billboard Top Latin Albums chart.

The artist was Daddy Yankee — real name: Raymond Ayala — a Puerto Rican reggaetonero little known outside the island at a time when reggaetón was just beginning to encounter commercial success. But in Puerto Rico, Daddy Yankee was king, the leader of a new musical movement born in the barrios and connecting with hundreds of thousands of fans who identified with a message created in their own streets.

Barrio fino’s success was duly noted by the industry; after all, it was the first reggaetón album to debut at #1 on the chart. Moreover, Yankee was an independent act, signed to his own label, although distributed by UMVD via a deal with another indie, VI records.

But then came the song.

“Gasolina,” the first single off Barrio fino, was written by Yankee with his frequent collaborator, Eddie Dee, and produced by Luny Tunes, the visionary production duo made up of Francisco Saldaña (Luny) and Victor Cabrera (Tunes) who continue to produce some of the top-performing artists and tracks in urban music. The song never rose past #17 on Billboard’s Hot Latin Songs chart because so few Spanish-language stations played urban music at the time. Instead, helped by remixes with Lil Jon and N.O.R.E., it got play on mainstream stations, peaking at #32 on the Hot 100 and propelling Barrio fino to become the top-selling Latin album of 2005 and of that decade.

Without becoming a major hit on Latin radio, “Gasolina” became the Latin song with arguably the most mainstream appeal since “Macarena,” played not only on US mainstream radio, but also all over the world, including in Europe and Japan. Most important, though, Barrio fino and “Gasolina” opened the door for reggaetón’s worldwide expansion. Today, the distinctive beat of the music dominates global streaming charts and has put Latin music and artists on the map in a way that was unimaginable a decade ago.

“I had a really different vision,” says Yankee now. “I could feel the impact reggaetón was having in the streets, in South America, in the streets of the United States. People were interviewing me even before Barrio fino, and I could see what was coming for the entire movement. I knew we were close to exploding. So I said, ‘Okay, I’m going to be the one to do it.’ And all the money I had, I bet on Barrio fino.”

The effect of “Gasolina” was profound at many levels. Musi- cally, it ushered a new and distinct genre into the marketplace. Unlike Latin pop or rock, reggaetón, with its recognizable dem- bow beat, was not a translation or adaptation of something that already existed in the mainstream market. Immediately dance- able, it had broad appeal, whether you understood the lyrics or not.

And in terms of business models, Yankee turned out to be a visionary. With reggaetón initially shunned by major labels, he put out the music on his own label, bringing to the table a new ownership model that many artists follow today.

At the end of the day, Barrio fino and “Gasolina” ushered in not just a musical movement but a lifestyle, built on a beat with irresistible global appeal that would eventually be the basis for other movements, from Medellín’s romantic reggaetón to Argentine trap.

The tipping point, however, was a song about gasoline, conceived by a hungry star on the rise, smack in the middle of a Puerto Rican barrio.

Daddy Yankee (Arist, Songwriter)

I was in Villa Kennedy [a housing project in Puerto Rico], because I had my studio there. I used to live there with my wife and my three kids. I only did music. It was very spontaneous what happened in Villa Kennedy. I heard a guy outside shout- ing, “Echa, mija, cómo te gusta la gasolina [Wow, girl, you really like gasoline!].” Song. That’s music for you. I thought, “I have to make a song that has that title—‘Cómo te gusta la gasolina.’ ” That’s what they shout at the girls who are always looking for a fancy ride to get to parties. I think that’s part of the reason why “Gasolina” was a hit. People were looking for some deep meaning to the track: Was it about alcohol, about drugs, about politics? And it’s a completely literal subject matter. “Gasolina” is one of the most wholesome tracks I’ve written. Luny produced it. The rhythm came from them.

Luny (Producer)

I started working in Puerto Rico in 2001 and, with Tunes, started to build a name for ourselves. We started to work on our own album, Mas flow [More flow], vol. 1.

I’d worked some tracks for [reggaetón duo] Héctor y Tito, and Daddy Yankee had been featured on one of those tracks. He liked it a lot and told me, “I’ll make a song for your album, and you can give me five beats for myself and I’ll record them.” At the time, if he were to pay me for the beats, it would be around $2,000 each but he could charge me $20,000 for being in one of my songs. He already was Daddy Yankee in Puerto Rico. He and Nicky Jam were the two hottest artists. I was dying to work with Yankee.

So, he recorded a song for my album. It started, “Métele con candela, Yankee, métele con candela [Go at it with fire, Yankee, go at it with fire].” The song is titled “Cójela que va sin jockey [Grab her she has no jockey],” but really, it’s “Gasolina, version 1” because it has the same structure.

It was one of my best songs and that was the first reggaetón album to cross over into mainstream Latin music. It hit in New York, and they were playing it in all the clubs. It opened the doors and I got tons of work. But then Daddy Yankee called, kind of pissed off. “Listen, I need my beat. I already recorded for you and you haven’t given me anything.”

I took that song, “Cójela que va sin jockey,” and I made some quick changes. I gave it to him, he went crazy, he liked it, and he even used the same structure as “Cójela” but with another concept.

Daddy Yankee

I went to Eddie Dee, we started to build the track, and we went back to the Luny Tunes.

I had the chorus and the flows. I record with a lot of flow. Most of the time, I start building the flows, the melodic structure, and then I add the lyrics. When I write hip-hop and rap, the process is different. There I’ll sit down and write lyrics first. But with reggaetón, which is more melodic, it’s more important to find the hook. In “Gasolina,” the chorus was very simple, very easy to remember. The word gasolina means “gasoline” everywhere in the world.

From DECODING “DESPACITO”: An Oral History of Latin Music by Leila Cobo. Reprinted by permission of Vintage, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Leila Cobo-Hanlon.