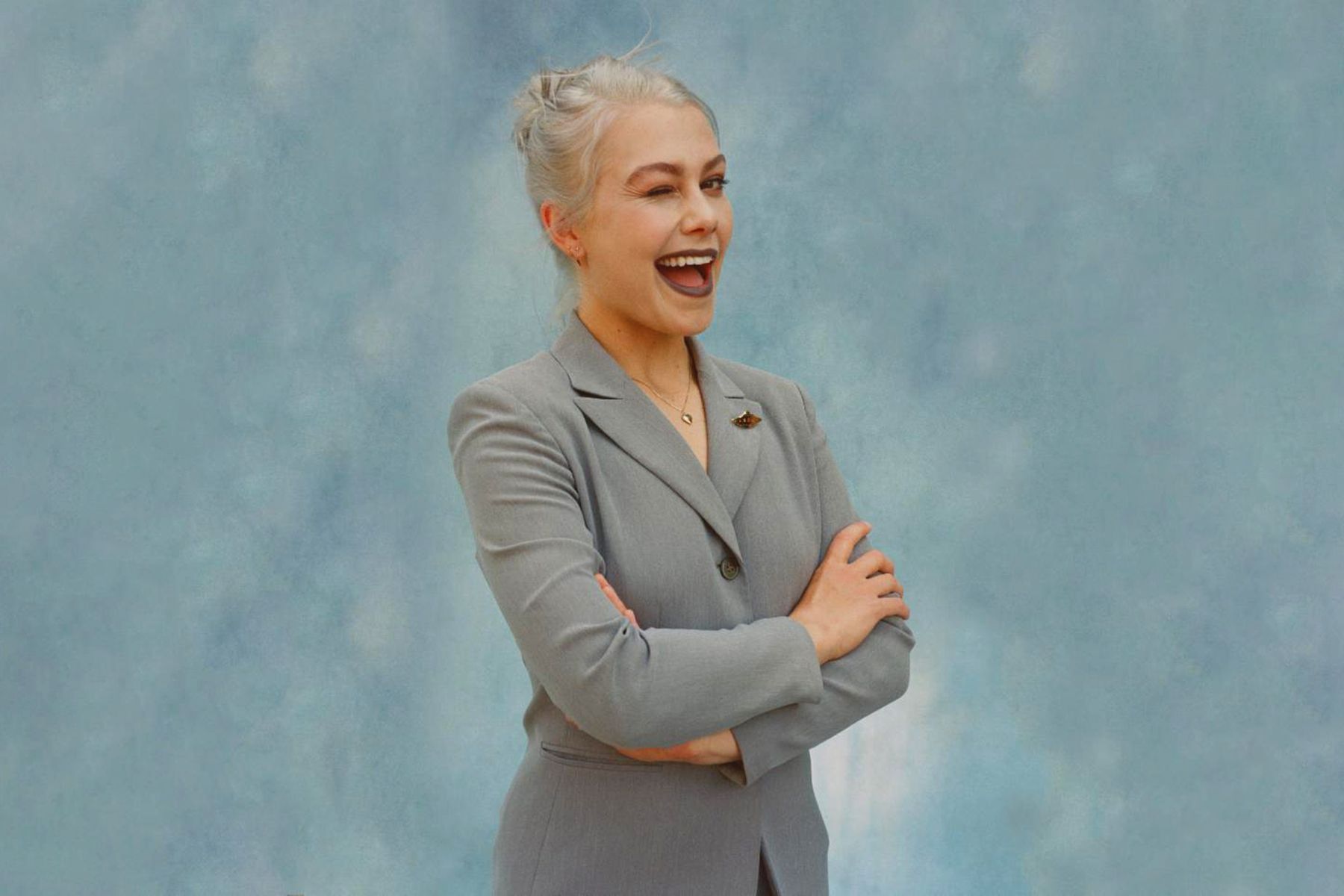

Dominican ‘Queen of Fusion’ Xiomara Fortuna Refuses to Leave Anything Unsaid

Back in March 2021, as the world reeled from its first year in and out of pandemic lockdown, Xiomara Fortuna was certain she didn’t have a second to waste. The Dominican Republic’s “Queen of Fusion” was working on her 15th studio album, Viendoaver, full of her signature amalgamations of merengue, jazz, gagá, and rock. For this new chapter, the 64-year-old artist also embraced trap, reggae, and dembow, showing respect to the country’s often maligned música urbana movement — and further cementing her legacy as one of the Caribbean’s most inventive and influential sonic artisans.

But two days before the album drop, a near-fatal heart attack threatened to send it all crashing down.

“That’s when I decided I wouldn’t leave anything unsaid,” reflects the poet, multi-instrumentalist, and alchemist, whose four-decade career is a monument to Dominican popular music, and an ornate braid of tradition, innovation, and joyful storytelling. She’s had a few dances with death and each time, she’s found a catalyst for creativity rather than a deadline: She was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2008 and uterine cancer in 2010, overcoming both and embarking on one of the most imaginative eras of her life. Boundary-pushing collisions of ancestral music and cutting-edge global rhythms have anointed her a patron saint of Dominican indie, influencing dozens of homegrown experimentalists and inspiring collaborations with new school peers Rita Indiana, Mula, Acentoh, Carolina Camacho, and Yasser Tejeda.

Fortuna spoke to Rolling Stone from Madrid, just before releasing her single “7mo viaje DE DÓNDE VIENES?,” out this Friday. Right now, she’s focused on output as she simultaneously develops multiple records, her usual modus operandi. “I’ve learned that life is but an instant,” she says, “and I plan on leaving my energy-made songs.”

Before contemplating the end, consider the beginning. Fortuna was born in 1959 in the province of Monte Cristi, located at the northern border between the Dominican Republic and Haiti. The region is a cultural nexus where multiple languages, culinary traditions, and spiritual practices converge, even when the relationship between both countries is severely fraught. In such a dynamic environment, Fortuna’s curiosity flourished. She took her first artistic steps in theater when she was 12 years old, and began writing songs in high school. She picked up her mother’s love of mangulina — a rhythmic predecessor to merengue — and absorbed protest music piped in via Cuba’s Radio Rebelde, which introduced her to trova and the Nueva Canción movement.

In the 1970s, Fortuna made her way towards the capital, where she attended the Autonomous University of Santo Domingo (UASD) and studied art history. Her musical tastes deepened, guided by merengue and jazz, though she was more interested in charting new waters than falling in line with canons etched by her predecessors. “I am a creator, and I defend my concept of art,” she says defiantly.

Fortuna began researching Afro-descendant rhythms and traditions from the Dominican countryside, going to bateyes, or sugar cane plantations, and rural communities in Villa Mella and San Pedro de Macorís. She learned about drums and ritual music, embracing the celebratory nature of gagá, pripri, and salve, while keeping respectful distance from religion. By the early 1980s, Fortuna had joined Kaliumbé, a band formed by guitarist and jazz composer Toné Vicioso, who’d become her mentor and gateway into the folk revivalism of Música Raíz. More than a simple roots collective, Fortuna, Vicioso, and contemporaries such as Luis Días, José Duluc, Irka Mateo, and Roldán Mármol underscored African heritage as inextricable from Dominican culture, a stance that remains controversial to this day.

“[In Dominican Republic], anything linked back to Africa is immediately associated and disparaged as Haitian in origin,” says Fortuna, drawing parallels with syncretic belief systems like Candomblé and Santería, persecuted for melding Catholicism and pantheons of African deities called Orishas. “We were told drums are bad, that they’re the devil. Even today people look down on drums because it’s Black music; as if Black people are not a part of the world. But drums stir something within you. Drums awaken ancestral memory.”

Fortuna is among the most musically radical of her peers, far more committed to originality than easy listening. She found an audience receptive to her unyielding experimentation in Europe and spent much of the Nineties touring the world music circuit, even appearing in a number of compilations by New Orleans-based label Putumayo. In 1999, she released what is regarded as her masterpiece: Kumbajei. A towering manifesto of sonic anthropology, the album poured decades of investigation into songs connecting the exuberance of Caribbean palo rituals (“Oxumaré”) with polyrhythms from Congo and Nigeria (“Leyenda Congo”), and parallel influences from reggae (“Juana la Loca”) and even country music (“Arrullo de Agua Pa’ Solei”).

“Everyone wants to teach you how to do this to make money or be more famous,” she says, explaining her adventures down the road less traveled. “But I cannot be unfaithful to my thoughts, my feelings, my ideas, my desire to create new sounds. I can’t even repeat things I’ve already done. I don’t have a mold. But if you look at who makes it to the top, they almost always follow a mold. A copy of a copy that eventually runs out of ink.”

The path of a trailblazer can be a lonely one — even more so for a woman hustling in deeply patriarchal Caribbean society. Fortuna recalls a time when, “for women, the label of artist was synonymous with prostitute.” But indefatigable gumption has positioned her alongside Dominican icons such as Fefita La Grande and Belkys Concepción, founder of merengue ensemble Las Chicas del Can; artists who challenged and shattered paradigms that saw women as fresh-faced singers, not composers and musical directors.

Her impact also looms over beautiful displays of Black pride from the likes of rapper Inka on the effusive “Party de Palo,” and Selektor Siete’s jubilant Afrovibe parties. And while happy to share her decades of wisdom, Fortuna also delights in learning from her younger peers. She’s a notable fixture at the queer bohemian throwdowns at Santo Domingo’s Parque Duarte, where she soaks up dembow and electro booming from makeshift soundsystems.

“I waited 40 years for artists who wanted to work with these sounds and stories,” she says. “An artist’s duty is to dream the future; that’s why I fervently support the música urbana movement. They are constantly criticized by the establishment, but also created their own codes to resist and survive in this world. They’ve broken barriers and I value that immensely.”

Fortuna released two more records in 2022; the hip-hop inflected Entre Luna y Babia, produced with Dominican jazz prodigy Isaac Hernández, and lush acoustic compendium ETAQUETÚVES, which explored the many musical, idiomatic, and culinary bonds between Africa and the diaspora. This most recent EP was produced alongside longtime collaborator Rafa Payán, one of the co-founders of emblematic Dominican pop-rock outfit Tribu Del Sol. On it, lyrical motifs are broken into “viajes” (or, “journeys”), drawing heavily from a 2009 trip she took to Nigeria and Benin.

“5to viaje SOPA DE OKRA” explores kinship through food over a musical palette that brings New Orleans blues guitar into a Villa Mella palo circle, while the historical scars of slavery are exposed in raw, cinematic detail on “6to viaje ÁFRICA VIVE EN MÍ.” “7mo viaje DE DÓNDE VIENES?,” meanwhile, is a diasporic retracing of steps that urges the listener to truly know themselves.

Of course, more music is already on the way. Fortuna is spending a season in Spain and working on her next album with musicians from Africa and South America. She also frequently produces shows at her Rancho Ecológico El Campeche, in the Dominican province of San Cristobal, and has grown into an ardent advocate for getting more local talent onto more local stages. But most of all, Fortuna remains committed to herself.

“To participate on the international stage, and to be able to compete, we needed to bring our own thing, our own flavor to the table. That’s not negotiable,” she says. “I think persistence is the key to reaching the ultimate goal, which is to love and value who we are.”