Creator of ‘Sober 21’ Zine Elia Einhorn Talks Getting and Staying Clean in the Music Industry

Elia Einhorn was about to turn 21 years sober when he set out to fill a vacuum he’d noticed in the music world: There were few places sober musicians could turn to for day-to-day advice and help navigating a world where alcohol and drugs often flow freely. Addiction and recovery stories — both the triumphs and tragedies — are among the most common narratives in popular music, but Einhorn saw that, while there were resources like Alcoholics Anonymous and MusiCares that could help musicians get sober, more practical support was lacking.

The founder of bands like Scotland Yard Gospel Choir and Fashion Brigade — and a host for Pitchfork Radio, Sonos Radio, and the Talkhouse Podcast — Einhorn had been toying with one idea for how to fill this vacuum, and in 2018 he posited it to two toher sober musicians he knew well: New Order and Joy Division’s Peter Hook and Andy Rourke of the Smiths.

“We were all talking about different addiction stories from our lives,” Einhorn recently recalled to Rolling Stone, “and I said to Peter, ‘I’ve got this idea that I’ve been kicking around. I don’t have a plan for it yet, but I wonder, would you feel comfortable doing an as-told-to with me about your experience as a sober musician?’ He said, ‘Yeah man, I’d fucking love to do that. I wish I’d had something like that.”

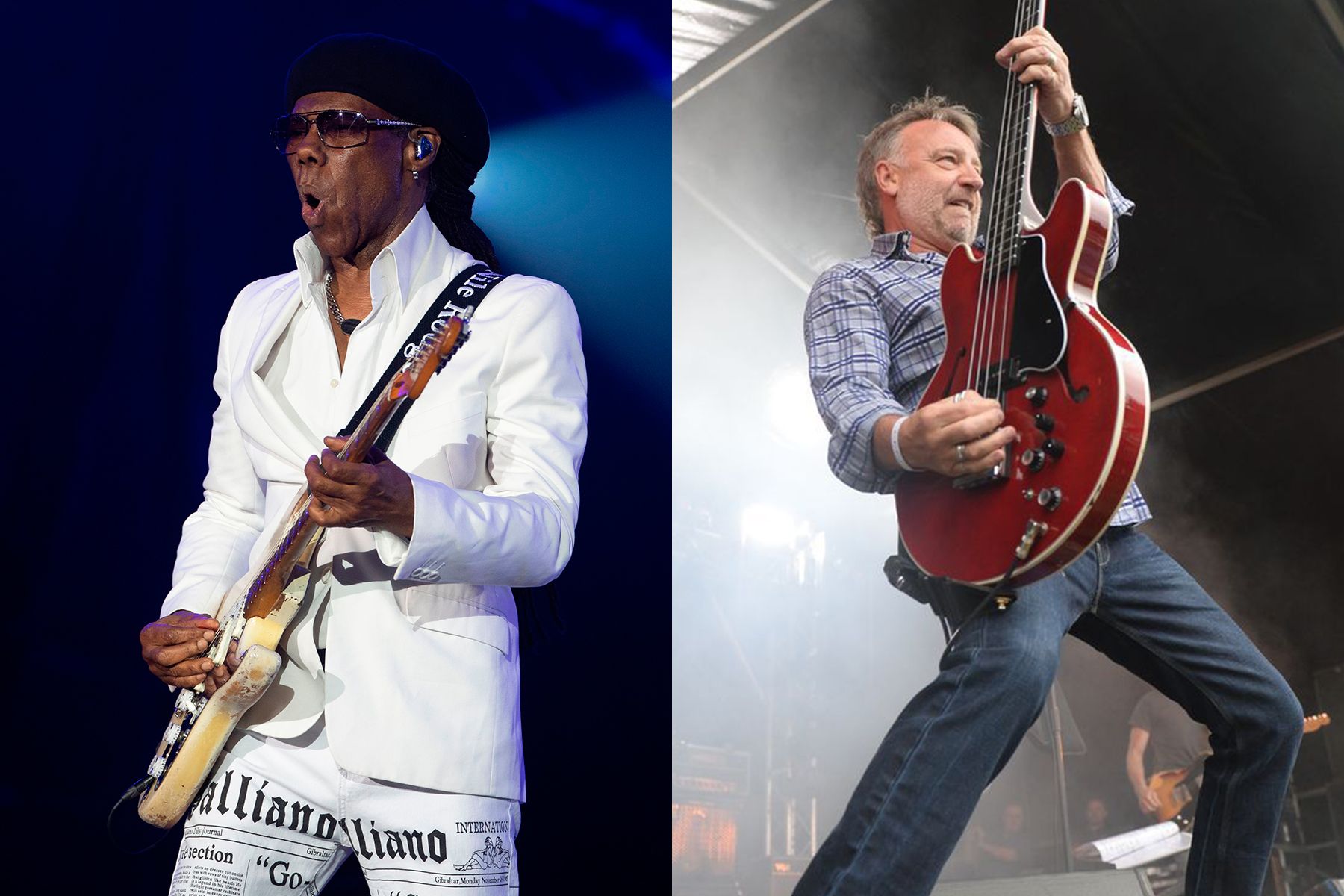

That interview with Hook is now one of 21 pieces in Einhorn’s new free zine, Sober 21, published May 18th by the Creative Independent, the editorial arm of Kickstarter. The compendium features a mix of essays, interviews, and as-told-tos with sober musicians including Hook, Nile Rodgers, Run-D.M.C.’s Darryl “D.M.C.” McDaniels, the Beastie Boys’ Mix Master Mike, LCD Soundsystem’s Tyler Pope, Moby, and the Pogues’ Cait O’Riordan.

“I wanted to take part in Sober 21 to let people know that being a touring musician without doing drugs and alcohol isn’t only possible, but can also be much better in the end,” Pope tells Rolling Stone. “Being on tour is hell while constantly on the rollercoaster of getting high and drunk, or it can conversely be the best thing ever when you’re taking care of yourself. I realize how hard making that decision to do it without drugs and alcohol can be, and maybe Sober 21 can inspire people to make that step.”

Emily Kempf of the band Dehd, another contributor, says: “I wanted to share my story in hopes it might calm and inspire those seeking a different way to live. That to be creative and successful you don’t have to be fucked up, you don’t even have to be miserable, you can be joyous and earnest and sober. That I’ve found this is the ‘real cool,’ to be genuinely happy and free, to risk being fully myself in front of everyone — sober.”

Sober 21 was the definition of a passion project: It took Einhorn three years to make in between his various radio and podcast duties, recording a new album with Fashion Brigade, and raising his kid. To find contributors, he first tapped into his own sober community of musicians met during his travels. The next batch was a bit harder to pin down as he brought the idea to artists outside his sphere, whose publicists were a bit baffled by a project with no proper release plan at the time. But that bafflement was soon supplanted by excitement as they learned more about the project. Almost everyone Einhorn asked to participate said yes, and just like Hook, they often offered the refrain, “I wish I’d had that when I got sober.”

As Einhorn notes in the intro to Sober 21: “Few professions are as incessantly perilous to the potential alcoholic/drug addict as that of being a musician.” To be a touring act, he continues, is to be paid to be in spaces where booze flows heavily; backstage, bands are often “plied with drink tickets,” while an alcohol company sponsoring a tour can be a huge financial boon. On top of that, there’s all the drinking that accompanies industry schmoozing, while many artists can turn to the drugs or alcohol that are readily available as a way of coping with the pressures of fame. “Alcohol and drug abuse is quite often not only normalized, but expected, encouraged, and even celebrated,” Einhorn writes.

Trying to get and stay clean amidst this milieu can feel impossible and isolating, but that’s one notion Einhorn says he wanted to push back against with Sober 21. “There is this huge scene of sober musicians and that it is absolutely in existence and waiting for you to tap into it,” he says. “You are not alone. People feel so alone and afraid coming in.”

Another key aim was to further dispel “this ridiculous myth of the tortured genius.” He continues: “I get people coming in with two weeks sober saying, ‘Elia, I think my fucking career is over. I’m never going to be able to write. I don’t know how I’m going to tour if I’m not drinking and using.’ And I kept telling each one of them the same things, and finally, the wisdom that sober musicians share is now codified in Sober 21. And that is: You will tour and you will fucking tour better, you will create music and it’s going to be fucking better and you are going to enjoy your life so much more.”

Indeed, reading the pieces in Sober 21, it’s clear that, as perilous a relationship as musicians can have with drugs and alcohol, there’s an equally fruitful one to be had with sobriety. Einhorn cites his interview with Nile Rodgers, who got sober in 1994 after a night that included getting literally carried out of Madonna’s birthday party by Rico Suave. At that point in his career, Rodgers had already created a litany of classics, but as he tells Einhorn, since getting sober, “I think I play guitar better than I’ve ever played. I think my shows are better. My songwriting is better. I’m coming up with more hits than I’ve ever come up with before, more collaborations. So it just shows you that maybe I didn’t have to relearn, I just had to not be afraid.”

In Sober 21, the advice is not one-size-fits-all. Contrast Rodgers’ story with Nimai Larson, who wrote about getting sober and realizing she needed to leave the band she’d started with her sister Taraka, Prince Rama. And while many of the contributors talk about how AA has helped them stay sober, the collection opens with an essay by Chastity Belt’s Annie Truscott, who writes about finding a personal sober mentor in Lillie West, who records under the name Lala Lala.

Even Einhorn’s story is uniquely revealing: Although he doesn’t write about it in Sober 21, he got clean in the late Nineties, well before he had any kind of music career. When asked the same question that opens many of the interviews in Sober 21 — “When did you know that you knew you needed to get sober?” — he recalls a day when he was floored by what he believes to be a combination of acid flashbacks and panic attacks. Fearful that he’d literally lost his mind and would have to be institutionalized, he went to rehab.

It was after getting clean that Einhorn founded Scotland Yard Gospel Choir, and he remembers the group’s first tours as equally thrilling and stressful as he learned what he could and couldn’t put up with on the road. One particular challenge at the time was the relative scarcity of cellphones in the early 2000s, so keeping in touch with an AA sponsor or sober buddy wasn’t as easy as it is now, when you can send a text from the backseat. Another lesson Einhorn learned later was the importance of getting a designated sober room in whatever hotel the band was staying in for those that didn’t want to be around drugs or alcohol.

“I had to have a place where I could be safe and feel like I wasn’t forced to be around it,” Einhorn says. “And I want to add: I still had a ton of fun. There were times when I was the last person up partying, stone-cold sober, having a fucking great time, because being sober and partying are not mutually exclusive. It’s just redefining the term partying.”

Sober 21 arrives at a unique moment for musicians, especially touring musicians: The year off brought on by the pandemic has given many the opportunity to reconsider some of the more hellish aspects of touring, whether that’s the lack of days off or the role drugs and alcohol can play on the road.

“So much of it is so ingrained in the infrastructure of touring,” Einhorn says. And while he’s had these conversations, too, he’s also found that the changes needed to overhaul that infrastructure and culture aren’t coming as quickly. There are some strides being made, he adds in a follow-up email, citing Royal Mountain Records’ decision to give artists a stipend for mental health and addiction services, as well as the work of Sound Mind, which is helping musicians with mental health issues.

But, he says, “It’s really tough. A lot of it at this point is going to be personal, and I hope that Sober 21 can be a small piece of moving that larger conversation forward. But if I’m being honest, for now, it’s got to be personal, it’s got to be about how do I take care of myself and the other sober people who might be on the road with me.”

Einhorn is also well aware that this issue affects countless others in the music industry beyond musicians, from managers to booking agents to venue workers to roadies. He hopes to do another edition of Sober 21 down the line, including one that expands its purview beyond those on stage.

“What I’d love to see is not necessarily another musician-specific resource, but just bringing the dialog to a whole new level, so people don’t feel any shame or fear talking about it,” he says. “I hope that people continue to understand that the disease of addiction is something that they have no control over getting, they just have control over what they do with it once they know they have it. And by speaking about that openly and honestly, that helps the newer generations — and not just age-wise, but people who need it — for them to see that it’s OK to talk about, and it’s safe and it’s ubiquitous.”