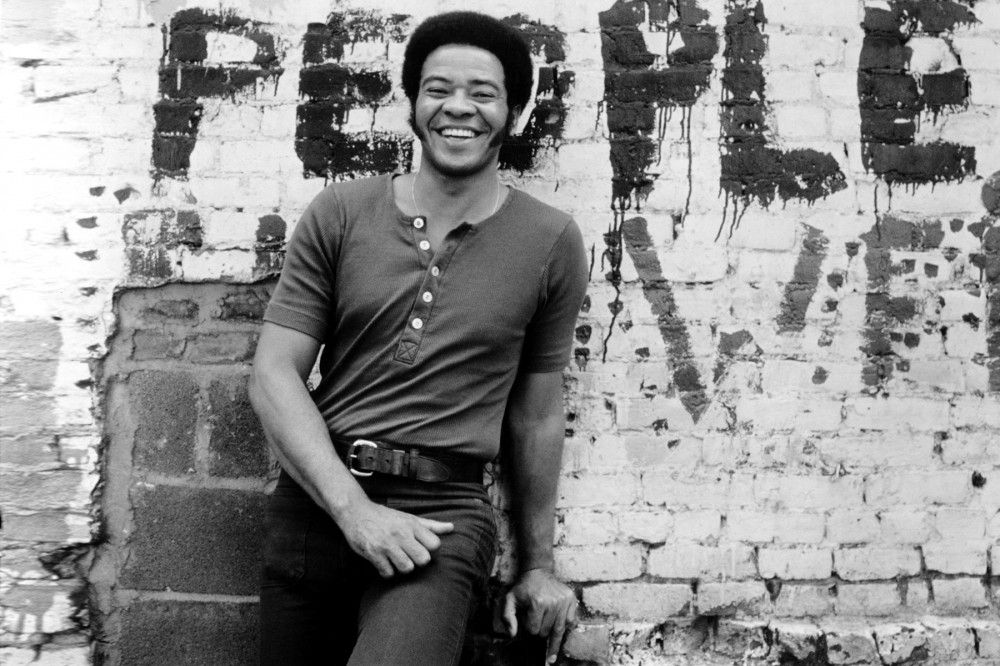

Bill Withers, Hall of Fame Soul Singer, Dead at 81

, the soul legend who penned timeless songs like “Lean on Me,” “Lovely Day,” and “Ain’t No Sunshine,” died Monday from heart complications in Los Angeles. He was 81.

“We are devastated by the loss of our beloved, devoted husband and father,” his family said in a statement. “A solitary man with a heart driven to connect to the world at large, with his poetry and music, he spoke honestly to people and connected them to each other. As private a life as he lived close to intimate family and friends, his music forever belongs to the world. In this difficult time, we pray his music offers comfort and entertainment as fans hold tight to loved ones.”

The three-time Grammy winner released just eight albums before walking away from the spotlight in 1985, but he left an incredible mark on the music community and the world at large. Songs like “Lean On Me,” “Grandma’s Hands,” “Use Me,” “Ain’t No Sunshine,” and “Lovely Day” are embedded in the culture and have been covered countless times. While many of Withers’ biggest songs were recorded in the Seventies, they have proven to be timeless hits. “Lean on Me” emerged once again in recent weeks as an anthem of hope and solidarity in the time of COVID-19.

“He’s the last African-American Everyman,” Questlove told Rolling Stone in 2015. “Jordan’s vertical jump has to be higher than everyone. Michael Jackson has to defy gravity. On the other side of the coin, we’re often viewed as primitive animals. We rarely land in the middle. Bill Withers is the closest thing black people have to a Bruce Springsteen.”

Withers was born July 4th, 1938, and grew up in Slab Fork, West Virginia, in the final years of the Great Depression. He was the youngest of six kids and struggled to fit in, largely due to his speech impediment. “When you stutter,” he told Rolling Stone, “people tend to disregard you.” He also had to endure incredible racism in the Jim Crow South. “One of the first things I learned, when I was around four,” he said, “was that if you make a mistake and go into a white women’s bathroom, they’re going to kill your father.”

He joined the Navy after high school and worked as a milkman in Santa Clara County, California, after he left the service. He later worked at an aircraft-parts factory. Music played a small role in his life until he visited a nightclub in Oakland where Lou Rawls was booked to perform. “He was late, and the manager was pacing back and forth,” Withers said. “I remember him saying, ‘I’m paying this guy $2,000 a week, and he can’t show up on time.’ I was making $3 an hour, looking for friendly women, but nobody found me interesting. Then Rawls walked in, and all these women are talking to him.”

That was all it took. He soon bought a cheap guitar at a pawn shop, taught himself to play, and began writing songs between shifts at the factory. A demo tape got into the hands of Clarence Avant, an executive at Sussex Records, and Withers was soon called into the studio to record an album with producer Booker T. Jones, bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn, and Stephen Stills on guitar. One of the first songs they cut, “Ain’t No Sunshine,” was a tale of lost love that Withers wrote after watching the 1962 Jack Lemmon-Lee Remick movie Days of Wine and Roses on television.

The album they recorded at that session, 1971’s Just As I Am, became an enormous hit and turned Withers into a star overnight. He followed it up with 1972’s Still Bill, which became an even bigger hit thanks to the leadoff single, “Lean on Me.”

Withers wrote the song shortly after learning to play the piano, but didn’t think much of it. His label disagreed, and it became a worldwide smash. “I try not to be too analytical about it because it wouldn’t be magic anymore,” Withers told Rolling Stone in 2015. “I didn’t change fingers; I just went one, two, three, four, up and down the piano. Lot of children come up and say, ‘That’s the first song I learned to play,’ and I’m thinking, ‘Don’t congratulate yourself; that’s pretty easy.’ You could make a tool and play that.”

But fame didn’t agree with him. He hated life on the road, his marriage to TV star Denise Nicholas became fodder for the tabloids, and his distrust of businessmen made him unwilling to work with a manager. “Early on, I had a manager for a couple of months, and it felt like getting a gasoline enema,” he said. “Nobody had my interest at heart. I felt like a pawn. I like being my own man.”

He was able to assert his independence and craft his own music on Sussex, but things grew complicated once the tiny label started to go bankrupt. He was working on a new album when he learned Sussex no longer had the ability to pay him. In a moment of rage, he erased the entire album. “I was socialized in the military,” he said. “When some guy is smushing my face down, it doesn’t go down well. Since I was self-contained and had no manager, my solution was to erase the album. I don’t even know which one it was, but it’s gone.”

When Sussex Records finally went bankrupt in 1975, he moved over to Columbia Records. It only added to his misery. “I met my A&R guy, and the first thing he said to me was, ‘I don’t like your music or any black music, period,’” Withers said. “I am proud of myself because I did not hit him. I met another executive who was looking at a photo of the Four Tops in a magazine. He actually said to me, ‘Look at these ugly niggers.’”

He recorded five records for Columbia and scored radio hits with “Lovely Day” and “Just the Two of Us,” but his heart was no longer in the work. During one particular low point, the label asked him to record a cover of Elvis Presley’s “In the Ghetto.” When he refused, relations with the label grew even more sour. “I was not allowed in the studio,” he said. “People say my career was 15 years, but it was eight years. I was not allowed in the studio from 1978 through 1985.”

His final album was 1985’s Watching You Watching Me. “They made me record that album at some guy’s home studio,” he said. “This stark-naked five-year-old girl was running around the house, and they said to her, ‘We’re busy. Go play with Bill.’ Now, I’m this big black guy and they’re sending a little naked white girl over to play with me! I said, ‘I gotta get out of here. I can’t take this shit!’”

The album was a commercial disappointment, and he retired from recording and even performing live, though in 2004 he made a rare exception for the 40th birthday party of Detroit Pistons owner Tom Gores. “His wife kept calling,” he said. “She said it was only for 150 people, but I kept refusing. Then the money] got so high that my nose started to bleed.”

The private gig found Withers and his band performing around 10 songs, with the crowd joining in for “Lean on Me.” It would be his last concert. Smart real-estate investments and royalties from his old records meant that money was rarely a problem. A comeback tour could have netted him a fortune, but he simply had no interest. “What else do I need to buy?” he asked Rolling Stone. “I’m just so fortunate. I’ve got a nice wife, man, who treats me like gold. I don’t deserve her. My wife dotes on me. I’m very pleased with my life how it is. This business came to me in my thirties. I was socialized as a regular guy. I never felt like I owned it or it owned me.”

As the decades ticked by, many fans forgot that Withers was even alive, which he found hysterical. “One Sunday morning I was at Roscoe’s Chicken and Waffles,” he told Rolling Stone. “These church ladies were sitting in the booth next to mine. They were talking about this Bill Withers song they sang in church that morning. I got up on my elbow, leaned into their booth and said, ‘Ladies, it’s odd you should mention that because I’m Bill Withers.’ This lady said, ‘You ain’t no Bill Withers. You’re too light-skinned to be Bill Withers!’”

In 2015, he made a rare public appearance when he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. “I still have to process this,” he said shortly after learning the news. “You know that Billy Joel line, ‘Hot funk, cool punk, even if it’s old junk, it’s still rock & roll to me?’ I’m happy to represent the old-junk category.”

Looking back decades later, Withers was still amazed at his success at a relatively late age in his life. “Imagine 40,000 people at a stadium watching a football game,” he told Rolling Stone. “About 10,000 of them think they can play quarterback. Three of them probably could. I guess I was one of those three.”