‘Goliath’ Honors NBA Great Wilt Chamberlain, Then Dishonors Him With AI

After his junior year at Kansas, basketball legend Wilt Chamberlain was ready to leave college to make some money. The NBA didn’t take players who left school early, so instead of playing competitively, Wilt joined the world-famous Harlem Globetrotters on a lengthy tour of Europe.

Seeing Wilt, one of the greatest players of all time, in a red, white, and-blue uniform, performing in a traveling basketball circus seems strange today. The decades that followed Wilt’s Globetrotter years have cast the great athlete in a narrow role: a killer, wholly devoted to the game, obsessed with winning. In this reading, Wilt’s decision to dribble around Europe and heave Meadowlark Lemon in the air during mid-game skits in fixed games when he should have been trying to win a title at Kansas betrays a lack of seriousness, a lack of devotion to the gnostic God of Competition.

This sort of talk, along with Wilt’s natural juxtaposition to ultra-devoted Celtics legend Bill Russell, would follow him around for his entire career. Goliath, a new three-part documentary on Showtime streaming on Paramount+ July 14 and debuting on Showtime July 16, makes no bones about why Wilt was in the game in the first place: for the good life that being a pro athlete can give you.

Some of that enrichment came from the thrill of winning, but more of it came other stuff: money, something Kansas wasn’t allowed to offer, a desire to see the world, something the Globetrotters could offer a young man from working class Philly (he played in front of Khrushchev!), women, modernist architecture, nice clothes, setting outrageous statistical records, and beach volleyball.

Pro sports grant players the opportunity to etch their name on the cup of destiny, to reach heights of competitive ecstasy, win the big one, prove their true mettle. It’s why we watch. But it is also a road to money, fame, and excess, depending on how judgmental you are prone to be. Everyone plays for themselves, to some degree or another. Chamberlain was strange in that he didn’t feel it was necessary to hide this, to playact like his main passion in life was the thrill of competition and not the creature comforts and ego-stroking that drive most of us. One can’t exist without the other.

Like Legend, Netflix’s documentary about the life of Russell, Goliath is a serviceable retelling of a fascinating life story, relying on archival footage and new interviews with principles from the time. Sitting side by side, tell both halves of the NBA’s first major rivalry: the habitual winner and the perpetual bridesmaid, the team player and the individualist, the competitor who vomited before every game and the icon of excess who commuted to Philly from New York because he just didn’t care for the dowdy vibes of his hometown. We prefer to fixate on the first guy — the grim, culture-setting winner tortured by purpose. But Wilt’s naked pursuit of money and pleasure also lives on in the guys that followed, no matter how much everyone tries to deny it.

The Celtics might have dominated the NBA in the Sixties, but it was Wilt who put butts in seats. He was the consummmate crowd-pleaser: 7-foot-1, handsome, faster and stronger than anyone else in the sport, an unstoppable wrecking ball on offense. His teams were some of the first squads we recognize as a standard NBA team nowadays: collections of role players rotating around a central star who devours possessions and defensive attention.

Wilt had a shrewd sense of his value to the employers. At a time before the NBA was flush with cash, before the CBA dictated how salaries were supposed to be structured and the threat of free agency loomed over every contract negotiation, Wilt acquired most of his leverage by openly threatening to retire, again and again. You won’t pay me? Fine, I can just go play with the Globetrotters or pursue my beach volleyball career while you make up your mind. The big money he made allowed him to get himself into whatever basketball situation he decided he wanted to be in as well. Wilt got coaches fired left and right, dictated the terms of how his squads played on court year after year, and moved from city to city, seeking whatever it was he was looking for from the game, and from life.

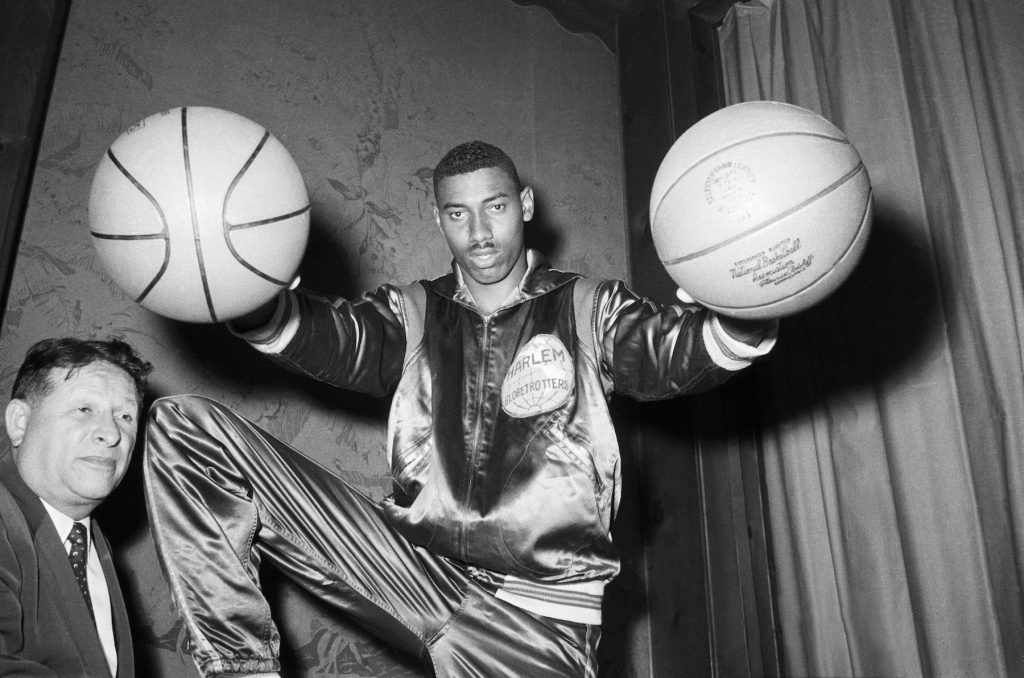

Wilt “The Stilt” Chamberlain, twice All-American at the University of Kansas, bedazzles Harlem Globetrotters’ boss Abe Saperstein with his basketball-palming technique on June 18, 1959.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

This naked ambition set new terms for talent in the NBA. After he commanded a $100,000 salary, Russell approached the Celtics and demanded the same amount plus one dollar. Wilt, being unembarrassed and unashamed of his own desires, created an environment where other stars were able to demand their share of the pie. Goliath details one intriguing sliding-doors moment that would have changed the league forever. He claimed that he was promised an ownership share in the Philadelphia 76ers after they won the title in 1967. Teams weren’t worth billions at the time, so this demand was fairly reasonable. When the Sixers’ owner passed away, his heirs nixed the idea. Wilt, annoyed at being denied the ultimate prize, forced his way onto the Lakers, ending this possibility for good. But what if it had happened? Would Russell have been compelled to make the same demand of the Celtics? Would this have become standard practice amongst a class of players? Would the early National Basketball Players Association have gone into its first CBA expecting that active players be granted equity in their teams? What would that league look like?

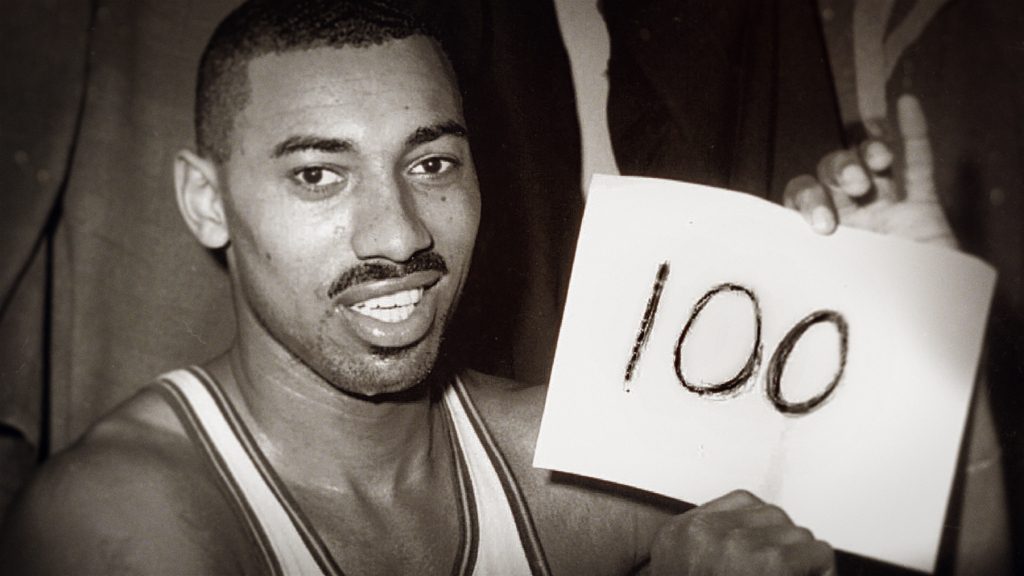

Wilt was an icon of id. He insisted on scoring the most points (famously netting a 100-point game), ate like a machine, plowed through women (he claimed to have slept with 20,000 women in his lifetime), dropped a fortune on clothes, drove insane cars. An interviewee in Goliath witnessed him chowing down on multiple hoagies and a “whole pie” after a game. His wardrobe, all bespoke (he was over seven feet tall, after all), was wild. His L.A. mansion of a bachelor pad was a modernist tribute to excess, featuring a swimming pool that let you travel to different parts of the house and a skylight right above his bed, so he could vibe with the stars at night.

Wilt was living out loud when pro athletes, Black athletes in particular, were encouraged to live quietly. Sports might be a grind for obsessive weirdos, but it is also a money-printing factory, and money is the sower and harvester of all desire. Sports media culture is quick to begrudge Wilt and his descendants the spoils of their victory, to begrudge any flash of material wealth from someone who didn’t win a title in the last year. Why aren’t they in the gym working on their game, screech dickheads on television, pretending they’re serving the God of Pure Sports, but really, just feeding the jealousy and maybe-light-racism of their audience. Wealthy, ostentatious pro athletes like Wilt are always ripe for criticism, when, really, the problems of society are profoundly detached from their wealth and contained in the wealth of the wealthier, who acquire their fortune from the sweat of the wage-earner’s brow.

Wilt Chamberlain celebrates his 100-point game in ‘Goliath.’

Showtime

Goliath is never more interesting than when it delves into Wilt’s relationships with women. No, he didn’t actually have sex with 20,000 of them: a book editor suggested the number for his book A View from Above, and he regretted the gambit almost immediately. But he did fuck. Habitually, without really seeking love or commitment.

How does a gender-equitable society deal with the fuckboy? He regards lovemaking as a sport, plows through lovers at an obscene clip, denies relational love, but is he bad or does he just like to fuck? In one scene, we see Wilt, whose book tour for A View from Above coincided with the news that Magic Johnson had contracted the HIV virus, coming into a wave of shit when he appears on the Geraldo Rivera show. Women in the audience chastise his lifestyle to his face, asking if he had been tested for HIV (he had, but he also didn’t think it was anyone’s business, really), accusing him, in short, of being a detached, predatory misogynist. He is visibly baffled and irritated by this turn of events. He did not see himself this way. He said he just liked fucking. His female friends (platonic and otherwise) who appear in the documentary recall that he was just… strange. Even a little needy. He might have been a lifelong bachelor but he was always looking for friends of both sexes, would talk on the phone for hours, and was a generous, caring friend. One very touching passage in the film concerns his relationship with Paul Arizin’s young daughter, who he befriended after she was diagnosed with cancer (Wilt’s parents were also taken by cancer).

Sex and friendship he was fine with. He just kept the other thing at arm’s length. One interviewee in Goliath, a friend and sometime lover of his, claims that they actually had to stop having sex because they began to love each other by accident, and Wilt was freaked out by the idea of being tied to one person. People he slept with were befuddled by his motivations, certainly, but they don’t claim to feel disrespected or used in any way.

Goliath is watchable and occasionally fascinating, in that sports-documentary sort of way. But there are some issues. Goliath’s directors and editors appear to have taken all of the archival footage that appears in the movie from YouTube. This decision really dings the visual appeal of the project, mixing beautiful, vintage photos of Wilt on the court with gunky-looking clips of the games he actually played in. Really shoddy work that could have been improved with a little extra money and effort.

Also lazy and uncanny: the decision to use AI to bring some of Wilt’s written words to “life” with a tone-deaf simulacrum of a dead man’s voice to narrate the proceedings. Doing this is ghoulish to begin with, as in the Anthony Bourdain documentary Roadrunner, but some of the reads the computer decides on are not even close to the sort that a human being would naturally choose.

These terrible creative decisions aside, Goliath is a wonderful primer on the life and times of the NBA’s Paul Bunyan. Flip it on and make up your own mind about this odd, complicated figure in sports’ early mass-media era.