Grady Kurpasi Went to Ukraine to Fight. Then He Disappeared

G

rady Kurpasi and Andy Hill dove to the ground as the forest around them exploded. There was a rapid pop, pop, pop as rifle fire pounded the dirt and trees and Russian infantry edged closer and closer. Kurpasi, a 49-year-old American former Marine sniper who volunteered to fight with the Ukrainian International Legion, and Hill, a 35-year-old British volunteer, desperately returned fire. Kurpasi called for help on a hand-held radio. But Kurpasi and Hill were on their own.

The two men crawled on their stomachs trying to make it back to their team roughly 600 meters away. Suddenly, another burst of fire. Hill saw Kurpasi get hit. A split second later, a bullet shattered Hill’s left arm. Before Hill could react, a Russian soldier jammed a gun barrel to his head.

Hill was led by the Russians back to their armored vehicle, where a tourniquet was applied to his arm. Still dazed, he realized he’d been separated from Kurpasi and had no idea if he survived.

Later that evening, in Wilmington, North Carolina, Kurpasi’s wife, Heeson, got a call from someone claiming to be from the Ukrainian International Legion. Kurpasi was dead, killed fighting in the south of Ukraine, they told her. But Heeson refused to believe it. Her husband had come home from so many deployments to Iraq, even surviving a suicide bomber.

“He’s a resilient and smart person,” she tells me. “He wouldn’t do a stupid mission like that.”

That night, Heeson texted her husband on WhatsApp.

“Grady, can you please call me?”

“Grady, I love you.”

“Please call me.”

Each message was received and viewed.

But she received no response, finally begging Kurpasi to return to the States in a message a few days later. It would be a year before he came home to her.

WHEN THE WAR broke out in 2022, the Ukrainian embassy in Washington, D.C., received thousands of offers from American volunteers, some with combat experience. People volunteered for all sorts of reasons: to fight for democracy, defend freedom, or just kill Russians. Some went because after 20 years of war with no clear victory, they were looking to shake off the hangover of Afghanistan and Iraq. It was a chance to use skills honed in the deserts of the Middle East and Central Asia in a righteous fight.

But this was a different battlefield. The American military machine was no longer behind them. The sound of a jet engine once meant air cover. But now it could mean incoming Russian airstrikes, changing the calculus. This was a fair fight, and no soldier looks for that on the battlefield.

About 100 Americans eventually joined more than 20,000 volunteers to be part of the International Legion for the Territorial Defense of Ukraine. Kurpasi was one of them. I didn’t know Kurpasi, but we had mutual friends and shared a hometown of Wilmington. I’d followed his story since his disappearance on April 26, 2022. I’d also covered the military for 20 years and knew a lot of guys like him — former Marines, SEALs, Green Berets scuffling with the transition to the civilian world.

After two decades in the Marines, Kurpasi was living with his wife and 13-year-old daughter. He’d been rejected from a doctoral program at Stanford he’d worked hard to get into, and had no plan B. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine stirred something. It gave him purpose. It allowed him to be Capt. Kurpasi again.

“The Russians were committing war crimes against the civilians,” he wrote in an email to George Heath, a former Marine colleague and friend. He’d already written about the mass graves in Bucha and how Russian troops were torturing and killing civilians. “Pretty bad stuff. I’m glad to be part of the force that is stopping this.” He ended the email with Slava Ukraini and Heroiam Slava: “Glory to Ukraine” and “Glory to the Heroes.”

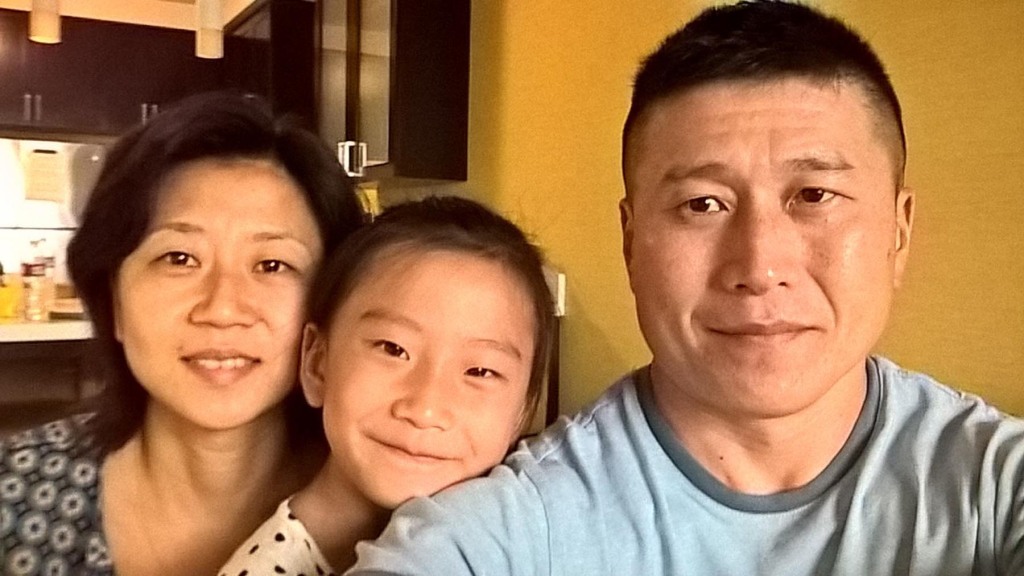

Kurpasi retired from the Marines in 2021 to spend more time with his wife, Heeson, and daughter, Katie.

COURTESY OF HEESON KURPASI

Earlier this year, I meet Kurpasi’s wife and a mutual friend in a local coffee shop nestled in a suburban strip mall on a cool spring morning. Over muffins and iced coffee, we talk about Kurpasi and rumors about his location. Heeson has a stillness and quiet stoicism about her. She speaks in a soft voice, every word deliberate and measured. She tells me about her husband’s friends from the Marines who banded together again to help find him. When we meet, Heeson is convinced her husband is still alive, wounded and in a hospital in Russian territory.

A few days later, I talk to the two friends of Kurpasi she’d told me about. George Heath and Don Turner served with Kurpasi when he was a Marine, and are working with a team of intelligence professionals and NGOs to find him. They tell me about the more than 100-page dossier of information they’ve put together on his disappearance in Ukraine and the months of searching for him.

Everyone I speak to this spring holds out hope that Kurpasi will return home alive.

KURPASI’S STORY BEGINS in Korea in the 1970s. His parents, Grady (Sr.) and Rosemary Kurpasi, waited about a year before the 13-month-old — named after his adopted father — arrived on a flight from Korea with 20 other children. They raised their son in Island Park on the south shore of Long Island, New York, where his dad says he was one of the only Asian American kids in the community.

“He had some problems growing up,” Kurpasi’s father tells me. “Sometimes it was people, you know … bigots. Other times he just wanted to know what was going on [with his heritage]. I tried to help out as much as possible.”

Kurpasi started college at Hofstra University, before he transferred to Stony Brook University, where he pursued a degree in computer science and met Heeson. She was from South Korea and immigrated with her family to New York, and they hit it off at a Korean drumming group. Together, the couple lived out West for a spell, working odd jobs in the late Nineties before returning to New York City around 2000. Kurpasi worked as a computer programmer and Heeson was studying to be a bartender when the planes crashed into the World Trade Center. Heeson was trapped in Lower Manhattan. When Kurpasi heard the news, he trekked from Queens to find her. That experience was seared into his memory. He enlisted in the Marine Corps and in 2002 was stationed in Camp Pendleton, California.

Before going to Iraq, Kurpasi wasn’t sure if he saw a career for himself in the Marines. But when he got home, he told Heeson he felt like he’d be leaving something unfinished. Every time he was close to his reenlistment date, he decided to stay.

After his first deployment, Kurpasi passed the rigorous three-month U.S. Marine Corps Scout Sniper School — which, within the past decade, has had a graduation rate of less than 50 percent some years. He completed a few more deployments to Iraq, and in 2007, he was awarded a Purple Heart.

Eventually, Kurpasi left the enlisted ranks to study linguistics at UCLA and soon earned a commission as a second lieutenant. He met his friends Turner and Heath when he was their platoon commander. They were impressed with Kurpasi from the start. He was “squared away,” they tell me, using military jargon for someone disciplined and efficient. “He still had that edginess to him of being an enlisted guy,” Heath says. “He knew how to talk with us.”

From 2015 to 2018, Kurpasi served a three-year tour in Korea, where he explored his birth country and worked as a liaison with the Korean military. But the decision to go didn’t sit well with his wife. They’d finally made a life in Southern California, and she didn’t want to uproot Katie, their then-six-year-old daughter. There was something restless about her husband, she says. It seemed like he was always looking for his place in the world. “He kept searching for something,” she says. “He felt his was some lost soul.”

KURPASI RETIRED FROM the Marine Corps in September 2021, and soon learned that his plans to study at Stanford were dashed. For two decades, Kurpasi saw a Marine in the mirror every morning, but now Capt. Kurpasi was just Grady Kurpasi. Like many veterans, it left him unmoored.

“There’s a real loss of purpose in life a lot of times,” Turner says. “It’s real hard to put your finger on what difference you make anymore — because you know that you used to make significant differences in numerous lives.”

Then, in February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky asked for “friends of Ukraine, peace, and democracy” to help fight. Kurpasi answered the call.

COURTESY OF THE PAT TILLMAN FOUNDATION

The evening before he left, Kurpasi called his father and told him that he was going on a trip to Europe.

“That was his exact words to me,” Kurpasi’s father tells me. “I’m going on vacation tomorrow, Dad. I’ll be back in about three months.”

His father asked why he wasn’t taking his family.

“I want to go to some places in Europe that I haven’t visited before,” Kurpasi said. “And I decided I’m going to do it on my own.”

Grady told his wife not to explicitly tell his father where he was going, and he assured her that he was going to help train and advise the Ukrainians. This wasn’t about combat. It was about using his skills to help.

“I think I took it very lightly because he made it through terrible deployments,” she says. “I thought he’s going to sit in the back and just do the advising position.”

Kurpasi left Wilmington for Ukraine on March 7, 2022. He made it to Lublin, Poland, and hitched a ride to Kyiv to find the right office to volunteer for the legion. He was there to fight.

ISSAC OLVERA, A FORMER U.S. Marine major who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, got to Ukraine a little before Kurpasi. They’d been in the Marine Corps at the same time but didn’t serve together until they met up in Ukraine, where Olvera was about to lead a platoon of 30 volunteers. After spending a few days getting the lay of the land, figuring out how the troops were organized, Kurpasi joined Olvera’s unit, falling in with other American and British fighters. By March 22, he’d told friends he was fighting in Irpin.

After more than a week there, Kurpasi started to recruit his own team — eventually called Raven — tasked with performing deep reconnaissance missions. It was like being back with the scout snipers. Kurpasi’s call sign was Deadman.

But Kurpasi was concerned about the leadership in the legion. He told Heath in an early-April email that it seemed like they were taking anyone they could get their hands on, and he wrote about another team leader who was accidentally shot during training. Kurpasi had concerns, too, about how the Ukrainians planned operations, which he talked to Olvera about. “It was challenging [for the Ukrainians] to have the same type of planning methodology that, as Marine officers, he and I would expect,” Olvera says.

Kurpasi would call home once a week, and messaged Heeson via WhatsApp. The calls were mundane.

“Food had gotten a lot better,” he wrote in an April 2022 email. “Now eating grilled chicken and stuff. Weather has not. Went from extreme cold and snow to really cold and wet. Effect is the same. After fighting in the desert for two decades, this is some real bullshit.”

Heeson still believed that her husband was working in an advising role — she had no idea he was in combat.

But he confided to his friends back home about life on the battlefield. He texted Turner about how long it had been since he’d showered. And he emailed Heath about missed opportunities due to unencrypted communications, asking him for help getting radios. “It is going to very literally translate into my ability to bring people home alive,” Kurpasi emailed Heath on April 11, thanking him for the gear sent to his team.

In mid-April, Kurpasi asked Turner to come over and be his platoon sergeant. He needed experienced leaders. “I looked at my wife and I said I can’t do it because I know a hundred-percent certain that if I go over there, I’m not making it home,” Turner says.

In an email sent a week before the ambush, things seemed to be turning around for Kurpasi. “I’m a Lt Again! I am now officially a [platoon] commander,” he wrote. “Have been running some missions no one else is interested in, also have one of the only teams that isn’t imploding/disintegrating (one team disbanded rather than run mission).”

At the end of April, Kurpasi’s team was on the front lines in southern Ukraine. Russian artillery shelled an observation point, and British volunteer Scott Sibley was killed. Two days later, Kurpasi’s team was tapped to hold the observation point, a camouflaged ditch used to spot Russian movements, until the Ukrainian army could send reinforcements.

“We weren’t happy to go,” says Andy Hill, the British fighter who was with Kurpasi during the ambush. “We knew how dangerous that OP was. We knew we were going to the same location as where one of our friends was killed a couple of days before.”

The observation post was off the side of a road overlooking some fields. Kurpasi and his group of six men got there on April 25. There was Kurpasi; Willy Joseph Cancel, a former U.S. Marine; Anthony Vo, a Dane; Pascal Feldcamp, a German; and Hill. Plus, two Ukrainians.

Their second day there, Kurpasi approached Hill about finding the location of a Russian mortar that had been firing at a nearby Ukrainian unit. Kurpasi and Hill were determined to avenge the death of Sibley, who had been part of the Raven team. Around midmorning, clutching Cz Bren 2 rifles, Kurpasi and Hill patrolled through a thick tree line next to the road. Kurpasi wore a helmet and plate carrier, with a yellow shirt and cargo pants. Hill was in green camouflage fatigues.

The trees and leaves provided cover. There was no sight of the Russians. But suddenly, Kurpasi stopped. Maybe he didn’t want to go any farther. Maybe he had a feeling the Russians were advancing and didn’t want to get too far out of range of the machine gun manned by his team. The two men waited 20 minutes to make sure the Russians hadn’t spotted them. They sat in silence listening for any rustle of leaves, the whispered commands of a patrol, or the approaching engine of a Russian armored vehicle.

When Kurpasi was confident they’d made it unseen, they started heading back. Then, the trees exploded in gunfire.

UKRAINIAN FOREIGN LEGION

BACK AT THE observation post, the 30 mm cannon from the Russians’ armored troop carrier ripped through the trees and dirt berm. Dirt and shrapnel filled the air as the rest of team Raven scrambled for cover. Cancel and Vo were torn apart by the barrage of bullets. Feldcamp dove onto the ground, crawling for half a mile before getting to his feet and sprinting another half-mile to nearby Ukrainian forces who were on their way to help.

A day after the ambush, legion drones spotted two bodies that were believed to be Vo and Cancel. There was no sign of Hill or Kurpasi. Back in Wilmington, Heeson heard from the State Department. “Kurpasi is missing in action,” Michael Abbott, the Department of State family representative, wrote in an email.

On April 27, Heath, unaware of the firefight, tried emailing Kurpasi: “Hey brother haven’t heard from you in a week. Hope all is still going well, let me know if you need anything else.… Stay low.”

His message went unanswered.

Legion members began mailing Kurpasi’s gear back to Wilmington. But Heeson didn’t believe he was dead. She reached out to Heath and Turner to ask for help finding him.

Reports of Kurpasi’s disappearance also started to circulate on an informal network of NGOs.

“Up pops a signal check from one of my volunteer intel analysts,” says Aces, a member of the military community who joined in the search. “He’s like, ‘Hey, man, you know this guy Grady is missing. Here’s his last known coordinates from his team. If you have any resources to help find him, let me know.’ ”

Aces (he asked me to use his nickname because he still works in Ukraine) is in the Air Force and runs a nonprofit providing relief services in Ukraine. He mapped out the ambush area and set up a trace on Kurpasi’s phone. “We thought we had his dead-to-rights location within a couple of days,” Aces says. “And then we started digging.” That’s when he heard from an Army buddy about Heath and Turner, who were leading efforts to find Kurpasi for Heeson.

A few days after the ambush, Hill was officially declared a prisoner of war by the Russians. In a video released by Russia’s defense ministry, Hill appeared in uniform, his injured arm bandaged in a makeshift sling across his chest, and his right hand caked in blood.

Slowly, word got back to the Kurpasi search team that Hill was the last person to see Kurpasi. On Hill’s Facebook page, Heath found a photo of Kurpasi standing with Sibley, the British soldier who was killed a few days before the ambush. Phil Bennett, who was in the process of returning Sibley’s body back to the U.K., commented on the photo.

Finally, a lead.

Heath reached out to Bennett, who told them he believed that Kurpasi was dead. He said Kurpasi’s body was taken to a morgue in Odessa Oblast, a province in southwestern Ukraine bordering the Black Sea. Bennett said the tip came from a friend in Denmark who paid for bodies in the vicinity of Kurpasi’s last known coordinates to be moved to Odessa. But a month later, another contact told Heath and Turner that they had called every morgue in the nearby village of Mykolaiv and found no sign of Kurpasi.

Meanwhile, Kurpasi’s phone was on the move.

Now teamed up with Aces, they tracked Kurpasi’s phone to Kherson, where it was at the same location where intel suggested Ukrainian prisoners had been moved. But there was still no announcement that Kurpasi had been captured, and stories were starting to appear on Russian propaganda channels claiming he’d been killed.

American media didn’t know about Kurpasi being lost in action until June — two months after he had gone missing — when The Washington Post published a story about the search. New tips started coming in. An International Legion sniper said Kurpasi was in Russian custody. Then, Heeson got a similar message. So did Josh, an independent intelligence analyst who was helping coordinate demining efforts. He had been searching for Kurpasi since June. (Josh still works in Ukraine and asked that only his first name be used.)

Those tips, plus the fact that Hill was still alive and captured, gave everyone hope.

They just needed to find him.

IN MARCH OF THIS year, I started talking to people about Kurpasi. I planned a trip to the ambush site, and reached out to a former NATO special-operations soldier to see if he would accompany me. He knew the area and had trained many of the Ukrainian special-operations soldiers operating there. He said it didn’t make sense that Kurpasi was a prisoner, especially when the Russians didn’t publicize it.

“Since the beginning of the invasion, an unwritten agreement has been the returning of the dead or prisoner exchanges, and both have been relatively fluid,” the NATO soldier tells me. “This one’s quite unique in that none of the missing-in-action next of kin have had any notification. Hill was captured in the same location as the others were. Yet still no word.”

But all of the tips said Kurpasi was alive.

According to Josh’s source, which he couldn’t disclose for security reasons, Kurpasi was shot in the face. The Russian soldiers believed he was from eastern Siberia, so they evacuated him to a hospital in a Russian-controlled area. Josh’s source claims he saw Kurpasi in a hospital in early May, and again in July. He was described as a man of Asian descent that matched all of Kurpasi’s physical characteristics. He had no tattoos and no visible marks. The person had been found in the same area that Kurpasi was last seen.

Aces says the hospital rumor seemed legitimate. He found imagery of the location and some intel saying that soldiers were being treated there. He was told that most were injured Russians or injured North Koreans.

“That’s what sparked my interest,” Aces says. “Grady being Grady, [he] could easily look and sound like a North Korean if he was still alive. But the report didn’t make sense because it said the dude’s face was blasted off. He wouldn’t be able to talk. Did they mistake Grady for a North Korean soldier? And maybe they’re just trying to keep him alive. Which didn’t meet the narrative that we were reading, where they were just cutting people’s heads off. So, in the back of our minds, this [was] a long shot.”

And source after source confirmed the same story.

“It very, very quickly turned from a situation where we didn’t expect to do anything other than recover remains into a very real possibility that he was still alive somewhere,” Josh says. “We had three or four different sightings of him from different people that had no connection to one another.”

But getting access to the hospital was impossible. It was located near several alleged prisoner-of-war camps in Donetsk, well inside territory contested by the Russians since 2014. Getting him out would take a Hollywood-style rescue mission.

“If we went on this crazy cannonball run to go rescue him at the same time, would we be sentencing everyone else in that hospital to death?” Josh says. “It turned into a huge ethical thing. We agreed across the board that it wasn’t feasible.”

Then, in September, Hill was among a group of 10 foreign prisoners released. But still, there were no reports about Kurpasi. Abbott, the Department of State family representative, had told Heeson days earlier that the prisoner-swap negotiations had stopped, and there had been no communication with the Russians since the Ukrainian counteroffensive started in Kharkiv earlier that month. (The State Department declined to arrange an interview with Abbott.)

At the end of September, Heath set up a video call with Hill. What happened after the ambush started to come into focus. Hill explained that as a Russian soldier put a tourniquet on his arm, he glanced at Kurpasi lying nearby. The Russian soldiers flipped Kurpasi on his back and then back on his stomach. But they didn’t seem to check if he was alive or dead. The Russians told Hill his whole team was killed. But Hill learned later that Feldcamp, the German fighter, had survived.

So Kurpasi’s family and friends held out hope. If the Russians lied about Feldcamp, maybe they were wrong about Kurpasi, too.

Then in November, the Department of State requested a DNA sample from Kurpasi’s daughter to help identify a body. Heeson provided the sample.

And they waited.

The search continued.

THIS FEBRUARY, 10 MONTHS after Kurpasi went missing, a team working with Josh started a new search of the ambush area, looking for anything that might give them a clue.

And back in Wilmington, Heeson got an email from Abbott that the FBI had been in contact with the Russians, who claimed responsibility for killing Kurpasi. The Department of State also sent a DNA sample gathered by the Ukrainians from an unidentified body to Heeson to see if it matched Kurpasi’s genetic profile.

The results came back negative.

More waiting.

Heeson kept imagining her husband clinging to life in a hospital in Russian territory.

IT WAS A BEAUTIFUL April day, and Turner worked on a fence at his house in Pennsylvania. As he took a sip of beer, he heard his text-message alert. He picked up his phone and a wave of relief and happiness washed over him. Looking at the text, the old Marine grunt felt tears well up in his eyes. It had been nearly a year of searching for their friend.

Finally, they’d found Kurpasi.

It was April 5, 2023, when Heeson received news there had been a positive DNA match with one of the three bodies found in a morgue in Mykolaiv. One of the bodies was beyond DNA testing, suggesting it could be Vo. The other two bodies were believed to be Kurpasi and Cancel.

When Heeson found out, she messaged her husband’s friends and called his father.

“I had been praying three, four times a day every day for his safe return,” his dad said, his voice cracking over the phone. “And it just wasn’t to be.”

Turner tells me a week after learning the fate of his friend he was happy in a lot of ways. “Not happy with the outcome by any means, obviously, but happy that we have been able to start some sort of closure for the family.”

What about the rumor that he was in the hospital? I ask.

“I’ll chalk that up really simple as hell,” Turner says. “It’s called fog of war.”

THIS SPRING, ABOUT a week after learning that Kurpasi was gone, I meet Heeson for a final time. Dressed in a baggy shirt and black coat, she shuffles slowly over to the table outside of the same coffee shop where we had first met about a month before. Nearby, a group of women talk happily about their weekends.

Heeson tells me the man in the hospital who they thought was Kurpasi died in September, according to sources feeding the team information. The source claims to have pictures of the injured man and took DNA samples, but Heeson hasn’t seen them, and Turner is doubtful any of that exists. But Heeson wants closure. Assurances it wasn’t her husband lying there in that bed.

“I don’t want Grady to suffer that long, waiting for rescue to come in the hospital,” she says.

Turner says it was Heeson’s strength that kept the team going. Today, it’s clear Heeson is still making sense of the news and the end of her husband’s life.

“I think he was doing a good-Samaritan act,” she says. “He had skills he could offer, and the timing that he can serve to use his skills aligned perfectly.”

Heeson says before he died, Kurpasi was thinking about his future. He mentioned a trip to Vietnam with his family, and had plans to reapply and earn his doctorate. But that was before that ill-advised mission.

Kurpasi returned to Wilmington in May, his casket shrouded in the flag. There are plans for a memorial in the summer. In the meantime, Heeson is left with questions and few answers. She’ll never understand what he was looking for in Ukraine. She only hopes he found peace, while she still searches for it at home.