Shine On Till Tomorrow: The Beatles' Breakup at 50

Fifty years ago, the broke up — it wasn’t the first time, and it wasn’t necessarily supposed to be the last. But the world finally got the message on April 10th, 1970. That was the day made headlines with a Q&A he sent out with press copies of his solo album McCartney, in which he casually announced a “break with the Beatles.” Why? “Personal differences, business differences, musical differences, but most of all because I have a better time with my family.” Temporary or permanent? “I don’t know.” Was he planning to make any more music with the band? “No.”

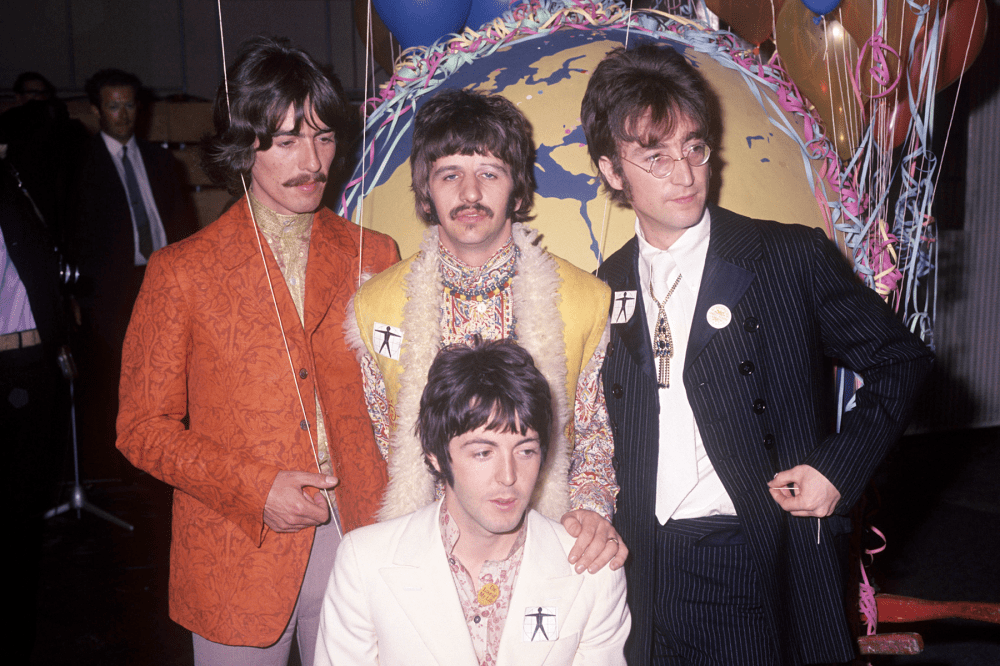

Paul had said things like this before, in public and in private — all four of them had. But this time, nobody made a move to deny it. When their new movie Let It Be premiered in London on May 20th, none of them showed up. The four Beatles never got together to watch the movie or listen to the album. The four Beatles never set foot in the same room again.

It’s not just the most legendary music split ever — it’s the world’s favorite story about how things fall apart. Along with the Fleetwood Mac of Rumours, the Beatles have come to symbolize the whole concept of breaking up, along with the idea of turning all that pain and despair into passionately soulful music. It’s a story that resonates in our own current Everybody Had a Hard Year moment: four friends struggling to hold on to each other in dark and confusing times, searching for a way to shine on till tomorrow.

John and Yoko briefly broke up in the Seventies, but as he put it, “The separation didn’t work out.” The Beatles’ split went the same way — they watched as their band got more famous and beloved every year. For 50 years, the world has obsessed over their breakup. Was it the money-men? The drugs? The wives? Or just growing older? At the time, most people figured it was a temporary snit. So did the four Beatles, at heart. A few days after Paul’s announcement, John said, “It could be a rebirth or death. We’ll see what it is. It’ll probably be a rebirth.”

Like everyone else, John, Paul, George, and Ringo watched the Beatles’ disintegration with shock and disbelief, with no idea how to apply the brakes. None of them really imagined this was the end. They kept feuding in the press — but when they complained about the band, they used the present tense. John fumed to Rolling Stone’s Jann S. Wenner, “It’s a simple fact that he can’t have his own way so he’s causing chaos.”

Even George, never accused of being the group’s cheerleader, kept right on talking about their future. He did a New York radio interview in late April, visiting on Apple business. George kept his cool when asked about tension between John and Paul. “I think there may be what you’d term a little bitchiness,” he said. “It’s just being bitchy to each other. Childish. Childish.” George, of course, wouldn’t dream of stooping to such petty emotions. “I get on well with Ringo and John, and I try my best to get on well with Paul.”

But as George saw it, they were still the Beatles, just clearing a few solo records out of their systems. “I think this is a good way, if we do our own albums,” George said. “I’m sure that after we’ve all completed an album or even two albums each, then that novelty will have worn off.” He laid out a rough but realistic outline for a future the band could have had. “We all have to sacrifice a little in order to gain something really big. And there is a big gain by recording together, I think — musically and financially and spiritually and for the rest of the world. Beatle music is such a big sort of scene — I think it’s the least we could do is to sacrifice three months of the year, at least, you know, just to do an album or two. I think it’s very selfish if the Beatles don’t record together.”

It’s strange to hear George talk about the band like it’s volunteering at the food co-op, but this was the most sensible and level-headed thing any of them said in the heat of the crisis. Unfortunately, it was easier to talk this way when he was the only Beatle in the room. The Phil Spector version of the Let It Be soundtrack arrived in May as their accidental tombstone. You know things are grim when the biggest smile on the album cover is from George.

How did this happen? It’s easy to picture a timeline for early 1970 where the hurt feelings blow over. Imagine: all four Beatles just step back and let it be. Take some time out, as they did in the fall of 1966 between Revolver and Pepper, letting Mr. Epstein mind the shop while they took off to India or Greece or Spain. Relax and float downstream. Jam with their famous friends. Do a few drugs. Go back to the band refreshed. They had a great new album to coast on — Abbey Road was their biggest commercial smash yet. Paul had just married Linda. John had just married Yoko. The second-to-last thing they needed was to start butting heads over their next project. The last was Phil Spector.

But John, George, and Ringo had a new business manager. Allen Klein came to the Beatles straight from the Rolling Stones, who he’d gotten under his thumb so completely, he ended up walking off with their entire catalog. When Klein first sniffed around the Beatles, Paul asked Mick Jagger for advice, but he shrugged, “He’s all right if you like that kind of thing.” In other words, he washed his hands and sealed their fate. Many observers over the years — not least Paul himself — have wondered aloud why he didn’t try to warn them. Was Mick conniving to trip up his rivals by letting them fall prey to his least favorite businessman? Could even Mick be that Machiavellian?

If so, it was his checkmate move. Two years later, the Beatles no longer existed and the Stones were bigger than ever. As Don Corleone’s consigliere would say, Jagger played this one beautifully.

With Brian Epstein watching over them, the Beatles were four soulmates who preferred to spend their free time together, even when they weren’t working. In August 1967, fresh from Sgt. Pepper, they went to see the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi lecture in London, and dug it so much, all four decided to drop everything and hop a train to Wales the next day for a meditation retreat. That’s how tight the Beatles were, right up to the final hours of Brian’s life. But that weekend, he died of an accidental drug overdose. Nothing was ever the same. By early 1969, the Beatles were no longer four longhairs road-tripping to hang out with gurus. They now spent an ungodly amount of time meeting with lawyers and accountants and blaming each other for it. “We’ve been very negative since Mr. Epstein passed away,” Paul said in the Get Back sessions. “That’s why all of us in turn have been sick of the group, you know.”

Without him, the Beatles were a sitting duck, waiting for the next hustler smart enough to buy John a drink and tell him what a genius he was. The lucky guy turned out to be Klein. A few hours of flattery at the Dorchester Hotel was all it took for him to score John’s signature on a piece of paper that was effectively the band’s O.P.D. certificate. George and Ringo fell in line (and like John, spent the early 1970s in litigation to get free); Paul held out. Klein negotiated a new record deal in September, cutting himself in on the proceeds, so he urgently needed new product in the shops. That meant turning Get Back into Let It Be. And that meant — after their exhausting 1969 — the Beatles now had a new project to fuss and fight over. Plus a new maniac in the room: Phil Spector. What could go wrong?

Spector was Klein’s guy, but John and George were enthusiastic. He arrived at Abbey Road and began rampaging through the Get Back tapes. When he got hold of “The Long and Winding Road,” it was a Paul piano demo, with John fumbling along on bass. He decided to add orchestral goop, a harp, and a choir — but to keep John’s inept bass part. It’s still there on the finished record — at the two-minute mark, you can hear Paul try (and fail) not to chuckle at his mate’s clumsy playing, in the middle of the line, “You left me standing here.”

The band’s bassist, not to mention the song’s composer, was around the corner at his pad on Cavendish Avenue. But he wasn’t consulted or even informed about what Spector was doing to his music behind his back. When he heard the results, he was horrified, as they knew he would be. Even the album sequencing was a piss-take; Spector started off “Let It Be” with Lennon’s mocking schoolboy voice saying, “And now we’d like to do ‘’Ark the Angels Come.’”

Paul’s plan to rush-release his homemade McCartney right on top of Let It Be was an obvious conflict. On March 31st, John and George sent Ringo over to Paul’s house with an envelope marked “From Us, to You.” It was not a friendly note. Even by Lennon standards — it’s his handwriting — the high-handed sarcasm was remarkable; at the bottom, George added, “Hare Krishna.” No wonder they chickened out and made Ringo deliver it. Paul was so outraged, poor Ringo went back and talked them into delaying Let It Be, so McCartney could come out in April. It could have been just another Beatle solo job — a half-dozen had already come and gone unnoticed — if not for the Q&A press release. Paul spoke to Rolling Stone in early April, his last statement before all hell broke loose. “No one has mentioned anything about doing another Beatles album.” And John? “He hasn’t called me and I haven’t called him but it doesn’t mean anything. We haven’t had an argument.”

But by the time Let It Be arrived in May, it was already a footnote to the messiest divorce rock & roll had seen. (“Breaking up” wasn’t a thing bands did yet — yet another Beatle innovation.) John finally saw the movie in June, in an empty San Francisco theater with Jann and Jane Wenner as well as Yoko. They bought their tickets at the door and sat unnoticed in the afternoon matinee. John broke down in tears.

Questions linger about whether the breakup could have been — should have been — a temporary glitch. All four made great music in 1970, from John’s confessional Plastic Ono Band to George’s triple-vinyl epic All Things Must Pass. (Both albums’ producer? Phil Spector.) What if they saved a few songs here and there for another Beatle album, in time for Christmas 1970? Side One: “My Sweet Lord,” “It Don’t Come Easy,” “Maybe I’m Amazed,” “Well Well Well,” “Apple Scruffs.” Side Two: “Every Night,” “Isolation,” “Wah-Wah,” “Junk,” “God,” “Isn’t It A Pity?” As for Ringo, he flew out to Nashville to make the wonderful country record Beaucoups of Blues, living out his boyhood cowboy fantasies but also sounding like a scared, confused adult watching the end of the world as he knows it. Ringo wrote the most candid response to the split, “Early 1970,” which he tucked on the B side of “It Don’t Come Easy.” He devotes a verse to each of his old friends, and hopes he gets to keep drumming with all three, whenever they’re in town.

The Beatles kept bouncing musical ideas off each other to the end — while Paul was singing “Let It Be,” praying to “shine on till tomorrow,” John was on the other side of town with “Instant Karma,” chanting “We all shine on.” They kept churning all their doubt and confusion into impossibly beautiful songs, even when it was the only way they had left to communicate. That musical dialogue never really stopped; like John said, the separation didn’t work out. It didn’t have a happy ending — the songs couldn’t patch them together. But the music the Beatles made together — even at the end—has always been a refuge that people turn to in times of trouble.