Inside the Bright Life of a Murdered Hollywood Sex Therapist

It was late into the evening of Valentine’s Day, a detail that would not go unnoticed later on. Dr. Amie Harwick, 38, had just gotten home from attending a burlesque performance, and she was texting with her best friend Robert Coshland about an upcoming trip to the U.K. He sent her the website for a restaurant in Edinburgh that had been recommended to him. At 1:01 a.m. she replied to say the restaurant looked cool.

Fifteen minutes later, at 1:16 a.m., police officers responded to a report of a woman screaming at Harwick’s Hollywood Hills home. Harwick’s roommate had called police, jumping over the fence to greet them. They found Harwick crumpled under her own balcony, unresponsive. She had been strangled and thrown out of her own third-floor window. She was rushed to the hospital, but later died of blunt force injuries to her head and torso. Her cause of death would later be determined homicide.

On Saturday afternoon, Gareth Pursehouse, a software engineer, photographer, and aspiring comedian, was arrested and held on $2 million bail, and charged with one count of and first-degree residential burglary, and of lying in wait. He faces the death penalty or life in prison without the possibility of parole if found guilty. His arraignment is scheduled for April 16th. (His public defender, Robin Bernstein-Lev, says in a comment to Rolling Stone: “Mr. Pursehouse is presumed innocent and it is the prosecution’s burden to prove otherwise in a court of law with competent evidence, not speculation, rumor nor innuendo, and to meet that burden beyond any and all reasonable doubt. It is my privilege to represent and defend Mr. Pursehouse and to challenge these allegations in court.”)

Harwick’s longtime friends were familiar with Pursehouse, 41. He and Amie had dated in the 2010s for just a few months. The relationship had ended badly: Pursehouse was abusive and controlling, according to two restraining orders Amie had filed against him in 2011 and 2012. Since then, Amie would occasionally refer to him in conversation as “my stalker,” but her friends say she had worked hard to recover from the trauma of their short-lived relationship, and he had receded into the background of her busy, vibrant life. She had largely forgotten about him, but, as the County District Attorney’s office currently alleges, he had not forgotten about her.

Those who knew Harwick casually knew her as a strikingly beautiful woman who was always dressed to the nines, making the rounds at burlesque clubs and go-go bars and art exhibitions and metal concerts and parties at Brookledge, a private performance space and a hub of the city’s magic community. “She dressed elegant with a touch of goth,” one person in her social circle said. “Very grown-up Wednesday Addams.”

But Harwick’s many close friends knew her as “brilliant and curious,” says musician and gallery owner Thomas Negovan. She was fiercely self-sufficient and driven, paying her own way through a masters degree at Pepperdine University and a doctorate from the Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Sexuality by holding multiple side gigs at once: modeling, bartending, fire-eating, go-go dancing. She was drawn to darkness: to the occult, to Charles Manson Family murder victim Sharon Tate (whose bras she once bought at an auction), to ethical taxidermy, to the preserved organs in jars on display at Philadelphia’s Mutter Museum, which she giddily made her friends visit on a trip to the city. There was an exuberance to this love of all things gruesome and unholy, says Dr. Hernando Chaves, a sex therapist and Harwick’s longtime friend. “The darkness made her feel alive and happy,” he says. “Even in the hardest times of her life she was always enthusiastic.”

Above all else, she was a rarity in Hollywood: a genuinely empathetic and caring person. “She took her natural way of connecting with people into her therapy world and that’s what made her an effective therapist,” says Coshland.

Which is why, in the weeks following her death, her loved ones were dismayed to see the media coverage surrounding Harwick focusing not on her life nor her work, but on, as Coshland puts it, her “proximity to celebrities” — specifically, to Drew Carey, the affable host of The Price Is the Right, to whom Harwick was once engaged. “It was so frustrating to see the media focus on her celebrity ex,” says model Emily Sears, who was Harwick’s patient for two years. “She was just a woman who was passionate about what she did.”

Drew Carey and Amie Harwick, pictured here in 2017, had been engaged.

Photo by Michael Bezjian/WireImage/Getty Images

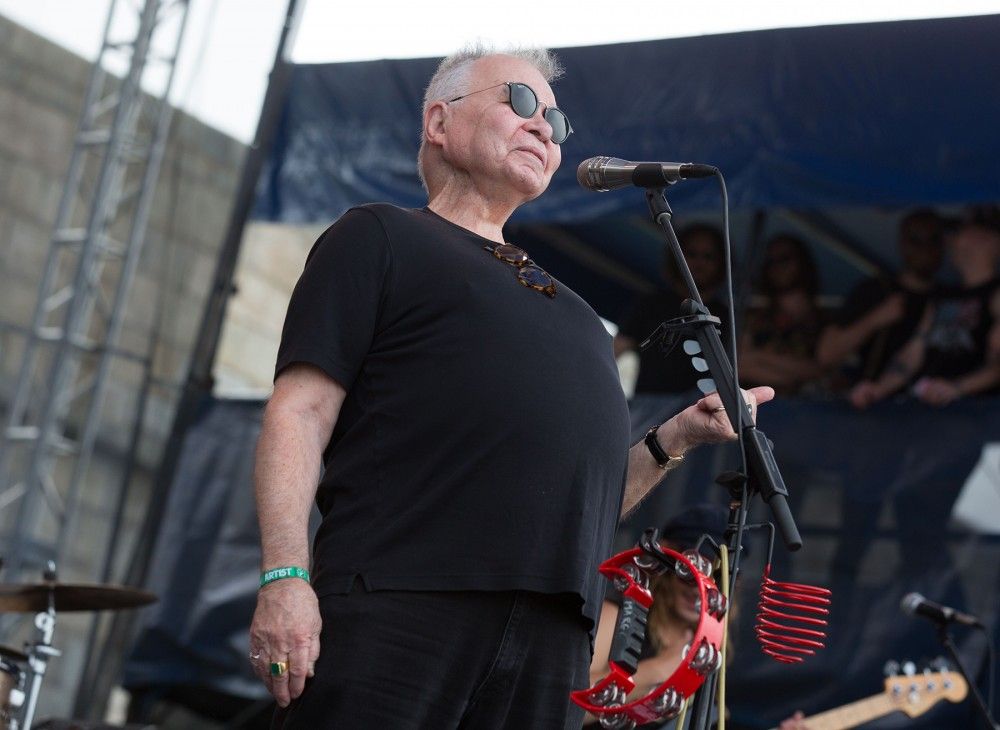

Harwick grew up in Lansdale, Pennsylvania, the adoptive daughter of Penny and Tom Harwick. Her family was close, and she would regularly talk about flying home to attend their annual cookie parties. In high school, she worked at the local mall’s Wet Seal and Bavarian Pretzel, idolizing artists like (whom friends say she later briefly dated) and Depeche Mode. “I hung out with the goth kids and the rocker kids and everyone was getting in trouble,” she said in a 2011 video for one of her modeling gigs. “I was trying to figure out who I was.” She fell in love with a musician for a heavy metal band and married young, moving to Los Angeles in 2001.

In typical L.A. fashion, Harwick became something of a master of self-reinvention. In one photo from high school, she wears brown matte lipstick, a shock of teased blond bangs falling over her kohl-rimmed eyes; right after she’d just moved to California, one friend says, she wore Juicy Couture sweatsuits and self-tanner, not having yet perfected the glamorous, vintage-inspired aesthetic she’d later rock in red carpet photos. But there was a drive and a fierceness to Amie that many of her peers lacked, says her friend, heavy metal band Bad Wolves frontman Tommy Vext. “People come to L.A. to redefine themselves but rather than do work, they just pretend to be somebody else and get by on that,” he says. “Amie was just a different kind of person.”

At first, Harwick started working as a personal trainer, releasing a workout DVD called Fit to Rock, and modeling under the name Amie Nicole. With her ink-black hair and skin the color of clotted cream, Harwick fit in snugly with the Suicide Girls aesthetic that was gaining prominence in the mid-2000s. It helped that she bore a more-than-passing resemblance to Dita von Teese, and the two actually traveled in overlapping circles (though friends say they were often chilly toward each other). She was adept at networking, procuring the phone numbers of A-list celebrities with a facility shared by only the exceptionally confident. “She’d be a fan of someone and she’d say, ‘I’m gonna meet that person,’ and she’d make the phone calls and go do it,” says Coshland. In high school, for instance, she’d idolized David Lynch, only to befriend Mary Reber, the owner of Twin Peaks’ Laura Palmer’s house.

At a go-go dancing gig in early 2010, she met Pursehouse, an IT specialist and aspiring comedian who also worked as a photographer. Pursehouse was 6’4″ and wholesome-looking, a detion from the Sunset Strip metal types Amie usually dated. But her friends were not overly impressed. “To me Gareth was just another L.A. Ken doll failing to become an actor or comedian,” says Vext. “There was nothing special about him.” Another longtime friend of Amie’s says Pursehouse reminded her of another blandly handsome, outwardly pleasant man: Ted Bundy. “He did a lot of mirroring,” says the friend, who asked not to be named. “You’d say, ‘I love chocolate milkshakes,’ and he’d say, ‘Oh my god, I love chocolate milkshakes!” She compares him to the aliens from 3rd Rock From the Sun, “trying to imitate how he thought humans behaved.”

While they remember Pursehouse being overly solicitous of Amie to a degree that they found uncomfortable, Amie didn’t feel that way, at least not early in the relationship. Vext attributes that in part to Harwick struggling with a fear of abandonment, which she and Vext traced to being children of adoption; The Primal Wound, a book about the psychological effects of adoption, was one of her favorite texts. “Sometimes with people with abandonment issues, it’s better to feel needed rather than wanted,” he says. “I could see how someone like Gareth having an unhealthy obsession could have made her] feel safe.”

A year and a half later, in June 2011, Amie filed her first restraining order against Pursehouse. In court documents, she alleged that on multiple occasions, Pursehouse had “choked me, suffocated me, pushed me against walls, kicked me, dropped me to the ground with force, force-restrained me, slammed my head into the ground and punched me with a closed fist.” That request was dismissed for lack of prosecution, which sometimes means that the petitioner chose not to follow up; while it’s unclear why Amie chose not to the first time, she was granted another restraining order in 2012, alleging that he had pulled her out of a car, giving her a bloody nose, and left her on the freeway. She also alleged that he had broken into her apartment multiple times and smashed her picture frames, texting her the chilling rejoinder that “things will get worse.” She never renewed the restraining order against Pursehouse (by California law, restraining orders cannot exceed five years), possibly because she was terrified to appear in court again with him, as would have been required for her to renew the restraining order, according to the friend who asked not to be named.

In the intervening years, someone continued to terrorize Amie. Every few years, she’d find cruel posts about her of unknown authorship popping up on an infamous gossip website. Once, before a long trip, she asked Chaves to watch her cat Marquis at his house, because she was afraid someone would break in and “do something to her] cat,’” he recalls. Yet Harwick was never able to identify the source of the harassment. Though she suspected Pursehouse, she also suspected a former female friend, who had previously sent her harassing text messages and emails, could have also been the culprit. (Harwick filed a restraining order against this friend in 2015.)

Ironically, it was in part such harassment that led Amie to her most fulfilling role, as a therapist specializing in sex and relationships. Although she had initially hoped to specialize in family counseling, Harwick had lost her job working with juvenile offenders after someone sent nude photos from her modeling days to her employer. “She felt like it was unnecessary and stupid that she’d lose jobs over nude photos she’d done,” says Coshland.

As a result of this experience, Harwick pivoted to relationship and sex therapy, finding particular fulfillment in treating people with marginalized sexual identities, such as sex workers, kinky, or non-monogamous people. This made her somewhat of a rarity in the mental health field, as many sex workers find it difficult to find mental health providers who do not judge them for their professions, or encourage them to leave. “It’s incredibly hard for adult performers to find mental health help without an element of social judgment,” says Gustavo Turner, an adult industry journalist and news editor at who knew Harwick socially. As a former goth kid with friends in the BDSM and kink communities, Harwick felt uniquely equipped to “stand up for those marginalized for their identities,” says Chaves. At the time of her death she had started working with Pineapple Support, an organization of sex-work-positive mental health professionals that had been founded in late 2017 in the wake of a rash of adult-industry suicides.

In addition to this work, Harwick had her own practice in West Hollywood, where she saw clients like Emily Sears, a model who coincidentally had had her own horrifying partner-turned-abuser and stalker almost a decade ago. At the time, Sears had no idea Harwick had had her own experiences with a domestic abuser; her therapist had never brought it up. But Harwick’s own experiences clearly informed how she was able to relate to her patients. Sears describes her as professional, warm, and empathetic. “She helped me deal so much with my fears of the past and my fears of it happening again in the future,” says Sears.

Robert Coshland and Amie Harwick.

Courtesy of Robert Coshland.

Throughout her time in L.A., Harwick had dated a number of musicians and celebrities, but her relationship with Drew Carey, the 61-year-old comic and host of The Price is Right, was special. Carey, who she had met through their mutual friend, Full House producer Jeff Franklin, was dissimilar to most of her exes, in that he was genuinely “a nice guy,” says Coshland. “When she started dating Drew, we were like, ‘Oh finally.’” In late 2018, however, Carey and Harwick broke up. Though friends declined to comment on the reason behind the breakup, other than to say they had differing communication styles, Harwick was devastated. “It was one of the few moments I’d seen her in pain and crumbling,” says Chaves. (In an email to Rolling Stone, a spokesperson for Carey declined to comment, saying he would not be giving interviews; on February 17th, he posted a photo of him with Harwick on Twitter, writing, “I hope you’re lucky enough to have someone in your life that loves as much as she did.”)

On January 17th, 2020, Harwick was set to appear on a panel about mental health and counseling at Xbiz, an adult industry business conference and awards show. Her appearance was last minute; another Pineapple Support member had bowed out, and Harwick had gladly stepped in. She was about to walk the red carpet with Chaves when she spotted Pursehouse, who was attending as a photographer. According to Chaves and Coshland, to whom Harwick later related the incident, Pursehouse grew extremely agitated, yelling at Harwick, “You’re a hypocrite,” and, “You broke my heart.” It had been nearly a decade since they had last seen each other.

Following Pursehouse’s outburst, Harwick excused herself to “go into therapist mode” and deescalate the situation, says Chaves, who saw them sitting together on a bench by the restrooms and talking while he was waiting in line to walk the red carpet. “He was flailing his hands,” says Chaves. “You could see there was a lot of angst or distress or pain.” Later, during the ceremony itself, Pursehouse approached their table to continue the conversation with Harwick, during which she excused herself again to sit and talk with him in the same area. To his knowledge, Xbiz security officials did not intervene during the initial altercation, Chaves says. (In a statement, Xbiz management said, “Gareth was one of many qualified photographers and members of the press credentialed to cover the event and had previously covered this event. The event is staffed with many security personnel to ensure the safety of our guests. This year, there were 26 security personnel on site.” They declined to comment further.)

After the ceremony, an extremely rattled Harwick sat with Chaves at a diner, unpacking the events of the evening. According to Chaves, they talked about buying mace or pepper spray, as well as changing the locks on her doors. They talked about going to the police. Chaves offered to sleep over, but Harwick declined, saying she had a new roommate in her house and felt safe. So they finished their food and went home. Harwick later told Chaves she’d gotten mace and pepper spray and had a handyman add locks. “I felt she was doing everything she needed to do to protect herself,” he says. “I couldn’t envision anyone would go this far.”

What happened in the early morning hours of February 15th is still not entirely clear. But according to a statement from the LAPD, police investigation of Harwick’s home “revealed possible evidence of a struggle in the upstairs as well as forced entry to the residence”; surveillance footage of the neighborhood later showed a white man dressed in all black in the area. According to the statement, “detectives learned that victim had recently expressed fear about a former boyfriend and… the victim had seen this former boyfriend two weeks ago.” Friends went through the same thought process, flashing back to what had happened at Xbiz the moment they heard that Harwick died. “She’d even said, ‘If anything happens to me, it’s Pursehouse],’” says Coshland.

Pursehouse was arrested on Saturday, but made bail on Tuesday night. He was re-arrested again the following day. Two of Harwick’s friends tell Rolling Stone that in the interim, guitarist Dave Navarro, who they say was a friend of Amie’s, had contacted the police, having learned from mutual friends of Pursehouse that he erroneously believed Harwick had cheated on him with Navarro during their relationship. Navarro told at least one of them he believed himself to be in danger, and on his Instagram story, Navarro said that he did call the police to re-arrest Pursehouse back into custody, as “friends were alerted he meant to target another victim.” But when reached for comment, a spokesperson for Navarro said he only called the police as a “concerned friend” and an advocate for domestic violence survivors, to ensure he wouldn’t remain out on bail. (Navarro’s mother was also killed by an abusive ex-boyfriend.) The spokesperson also denied Navarro and Harwick had had a relationship. “They hadn’t spoken in a while,” the spokesperson said. “They weren’t close friends.” The LAPD also declined to comment, directing Rolling Stone to their statement about Pursehouse’s arrest.

Courtesy of Robert Coshland

Those who lose a loved one violently and abruptly often ask if there’s anything else they could’ve done to have prevented the tragedy. And even though we won’t know the facts of Pursehouse’s involvement until he is tried, in the case of Amie Harwick, who has become a totem for survivors of intimate partner violence in the weeks following her death, friends believe the only “what if” questions worth asking have less to do with circumstance and more to do with hard-and-fast policy.

What if, for instance, the state of California issued restraining orders without expiration dates? What if there was a stalker registry for those who had been served with restraining orders, the same way there is for sex offenders? What if stalking victims were not required to appear in court with their abusers to serve restraining orders, as would have been required for Amie to renew hers against Pursehouse? And what if there was early intervention for stalkers and domestic abusers to curb the risk of violence escalating? These are the questions that keep Harwick’s loved ones up at night. “If a child is potentially in danger we send out a social worker, we send out CPS. We investigate it,” says Chaves. “Why don’t we do the same with domestic violence?”

In the wake of Harwick’s death, a petition has circulated calling for the expansion of legal protections for survivors of domestic violence, which has garnered nearly 100,000 signatures. It calls for signers to support the passage of laws like SB 1141, which would broaden the definition of intimate partner violence beyond physical abuse to make coercive control, or a partner depriving another of personal liberty, an offense punishable by up to one year in prison. On social media, many have used the hashtag #Justice4Amie to lobby for such changes. “Everyone speaks out says how sorry they are when domestic violence] and Stalking Victims are murdered yet do nothing to help support reforms that will actually save lives,” one attorney and advocate for survivors recently tweeted. “This is why so many will continue to die.”

In the interim, however, other survivors such as Emily Sears — women who relied on Harwick to help them recover from their own trauma related to intimate partner abuse — are left to live in fear, knowing full well what the loss of Harwick, a trained professional who used all of the options afforded to her by the system, represents. “If this could happen to her — who knew what to do and is trained to help people in these circumstances — how are women supposed to process that? Not just her clients, but all women?,” she says. “If something like this can happen to the helper when this happens to other women, then none of us are safe. It just feels like none of us are safe.”

If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic violence, please call the National Domestic Violence Hotline (available 24/7) at 1-800-799-7233 or visit thehotline.org.